/**本文出自稍早前《多伦多星报》有关新中国60周年的系列文章之一,由该报亚洲部记者Bill Schiller撰写,文章刊发于9月26日《多伦多星报》。中文编译部分源自清衣江博客,文字、标点和姓名等有少许改动。特此收入本博客的“张国焘专栏”。Jack注**/

一个有可能成为毛泽东的人

张国焘,现埋葬在多伦多一处墓地,是在流亡中离世的一位党的创始人。

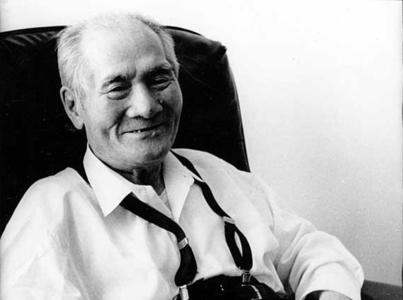

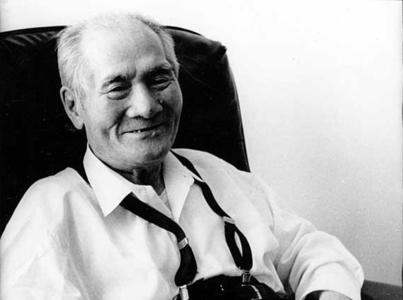

(资料图片:张国焘,1974年在多伦多,在他接受加通社唯一的一次采访时,他说:“我已经在政治上金盆洗手。”)

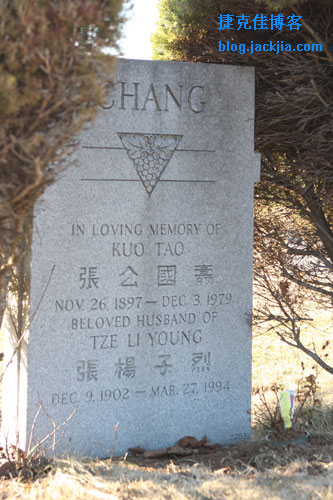

他的墓碑是简单,朴素,显然废弃了:藏在多伦多东部松山墓园的两处灌木丛之间。

但在墓地第5区2263墓址的地下依然躺着一位可能改变历史的人物的遗骸。

他的名字是张国焘。1979年12月他死在多伦多一家养老院……

他不为大多数加拿大人熟悉,曾经是中国杰出的政治和军事人物。

今天,有人认为他是有可能成为毛泽东的人,或精确地说:是唯一一位有可能超越毛泽东,在长征中上台成为中国领导人的人。

但是据两位受人尊敬的历史学家称,毛用狡猾奸诈和背信弃义的计谋,弄垮和放逐了他。

经过香港多年的流亡生活后,张于1968年来到了加拿大,在此平静地度过他一生的最后11年。

然而,尽管中国的宣传系统尽了最大努力把他抛进民族叛徒的历史垃圾箱,张的遗产将永驻人间。

下周随着13亿中国人准备庆祝中华人民共和国成立60周年–开庆祝会歌颂执政的共产党的辉煌灿烂的业绩时,中国人是欠了张国焘一笔债。

他是中国共产党的创始人。

他是“张主席”。于1921年在上海召开的党的第一次全国代表大会上。他是党的最高领导人之一。

他就是有这么重要的。

(张国焘墓地近况。从右下侧栽种的一小盆花来看,还是有人前来祭奠。摄影:捷克佳。时间:2009年3月15日下午5:43分)

然而,在位于贝奇蒙特路与圣克莱尔大道东的街角处的墓地里没有安放纪念张在历史上地位的牌匾。

张也许是想这样办的。1974年在他唯一一次同意接受的采访中,他告诉加拿大通讯社记者说:“我已经在政治上金盆洗手。”

很少有人知道他埋在那儿。

他毕生的妻子,杨子烈在1994年去世,被安葬在他身旁。

他的多伦多家庭的两个儿子以及他的孙子们先他之前来到加拿大–当今已经远离公众的视线。

(张国焘全家合影。江西省萍乡市上栗县旅游局提供)

一位住在多伦多附近退休的历史教授左光喧说:“没有人能够找到他们,”他认识张和他的妻子,但是,不知道是否出于偶然或诗意般的设计,张的墓碑面临东南方向–对着中国南部,江西萍乡他的出生地,就是从那里开始了他的传奇的故事。

在20世纪初,张前往北京,在北京大学获得大学的学位,当时毛泽东是那所大学一个卑微的图书馆管理员。不清楚是否他们两人曾在那里相见。

张是1919年五四运动的著名学生领袖–这次著名的中国学生运动播下了革命的早期种子–并最终导致铁路和纺织工人罢工。

但直到20世纪30年代,张才在中国建立了一支最强大的军队,他的迅速茁起对毛泽东是最大威胁,直到那时毛在党内的地位已经上升了。

不过,一些人认为张,而不是毛,或许会率领共产党在该国的血腥内战中赢得胜利,并可能迎来这个新生的解放了60年前成立国家。

2005年出版的由历史学家张戎和乔-哈利迪合著畅销书《毛泽东:鲜为人知的故事》中写道:“他坚实的学历资历足以使他成为中国共产党领导人。”

乔-哈利迪在伦敦说:“他是一个极为成功的军事指挥官,绝对是一位辉煌的将军–他像毛泽东一样强硬。”

哈利迪的书合著者之一和妻子张戎说“这将最终被证明是张毁灭的原因,毛已开始看出张对他的权力构成了最大的威胁.。”

戎说:“张国焘对于权力被剥夺有充分的准备,毛认为张是他见过的人中非常像他的人。因此,毛泽东认为他绝对必须搞掉张国焘。”

事实也的确如此。直到毛去世,他从此再没有遇到一个真正的挑战者了。

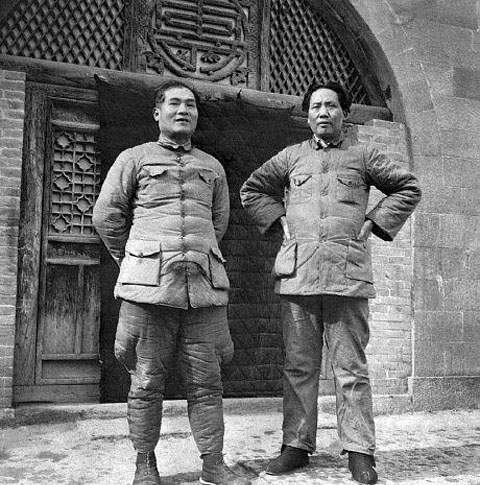

毛有暗中损害张的强烈的动机:当长征途中两支部队会合时–在20世纪30年代传奇的共产党人从国民党军队围困中突围,被迫退却,安全转移–张国焘是令人敬畏的,有8万军队士兵。

毛仅有1万军队士兵。

张欢迎毛到达他们在四川的会合地点时,就像一位主人欢迎一位客人。

杨子烈引用他丈夫的话说:“我曾经是中国舞台上的演员。”

(1938年 毛泽东和张国焘)

毛泽东知道,如果他想获得的最终权力,得先于张之前与俄罗斯支持者结成同盟–争取他们的认可–他不得不削弱,阻滞并最终摧毁张的红军。

哈利迪说:“毛为了垄断与莫斯科方面的联系,在军事上毁灭张国涛是至关重要的。”

毛泽东成功地通过将自己置于一种他动辄就可以“有条不紊地破坏”张国焘的军队的政治地位上,这点在作者经过10年的写作和精心研究的书《毛泽东:鲜为人知的故事》中有详尽的描述。

戎说:“毛泽东策划,以确保张的军队总是面临的最困难的地形和最残酷的战斗,–而且,看来,甚至还正面攻击过张国焘的部队。据2005年解密的一份前苏联档案指出,毛泽东曾私下向苏联强人约瑟夫-斯大林的一个特使吹嘘,他的部队就曾面对面地消灭了30,000张的士兵。(编译者注:这是谎言,这点连张在自己的回忆录中,都没有只言片语的涉及。)

哈利迪说:“这是一个惊人的启示。”

最后,毛胜利了。然后他的特使说服莫斯科,在真理报上宣布:“毛为中国人民新的领袖。”

张会坚持,拒不放弃,等待,但1938年他最终逃亡,投靠了反对派国民党,后来,在英国殖民地香港寻求避难。

哈利迪指出,“他并不像毛泽东精明于政治,”“最后,他让自己败给毛的计谋。”

哈利迪说,如果张赢得了权力,中国历史可能有所不同。

在毛泽东领导下把中国人民吓倒的可怕的灾害本来是可以避免的。

他说:“我认为张国焘不会发动像文革之类的事情,”这指的是从1966年到1976年的暴力和混乱的10年,在此期间,毛泽东鼓励中国青年毁灭和摧毁了中国社会的几乎所有的珍贵和传统的东西。”

“我也相信他不会造成大饥荒。”

发生在二十世纪50年代末的大饥荒是中国历史上记载的最大的饥荒,声称由于毛泽东的干部工作失职导致高达3800万中国农民饿死。

说哈利迪:“这需要一定的无情。”

他和张戎的书指出,张在他的军事生涯达到高峰时,开展自己的血腥清洗。但是都认为其巨大的破坏能力都远不及毛泽东的规模。

张叛逃后,党的宣传人员散布他的传言–到底是真实的或想象的–称张曾企图破坏和杀害毛。

不管真实与否,对有些人那些传言就是真的。在上海的中国共产党第一次全国代表大会纪念馆里,张在党的历史上的开创性的作用是公认的–但被不屑一顾。他被打上叛徒的烙印,因在长征中从事分裂党和红军的活动,被“驱逐出党。

另一方面,毛是光辉闪亮的。

在娱乐性地再现的,由感觉迟钝的真人大小的蜡像人物戏剧化地表现出来的历史性的1921年举行的党的第一次全国代表大会上,毛作为核心人物站在一张锈迹斑斑的桌子旁,带着幸福的辉光,滔滔不绝地对12位仰望着脸的信徒和两名来自共产国际代表发表演讲。

(2009年6月5日,游客在中共一大会址纪念馆内参观。新华社记者 刘颖 摄)

(栩栩如生的蜡像群将历史定格于中国历史上的伟大时刻:毛泽东手拿记录本认真发言,董必武、李达等共产主义小组代表和共产国际代表们仔细聆听。中国共产党新闻网)

张没有坐在桌子旁,实际上,坐在围会议桌而坐的代表之外,当毛泽东讲话时,张是唯一的一位蔑视地双臂交叉抱胸前听着讲话的会议代表。

但即使是博物馆警卫也不买宣传的账。

在最近一天下午,有个人在参观时说:“如果是根据历史事实张国焘应该处在会议中心位置。”但这不会获得有关当局的批准,虽然毛处于会议中心位置。这是获得批准通过的。

“后来张成了叛徒,所以你真的无法再把他放在这个中心位置上。”

另一个说,“这就是历史将由胜利者来改写。”

但是,在博物馆外的游客建筑工程师李晓芳不会受张曾是一个叛徒这一事实的欺骗。

她说:“我们真的认为他真的不是如此……我们只是觉得他的想法不一样而已。”

我们不仅仅只是相信教科书告诉我们。今天,我们更理性地思考。这是党内斗争的一部分。”

她惊讶地得知张安葬在加拿大。

“我们仅知道他死了。”

但张将永留人世间。

在香港,张开始写回忆录。

美国出生的作家罗伯特-埃尔冈特,81岁,现在生活在意大利,生动地记得那段时期。

埃尔冈特是50年代初帮助张英文翻译他的回忆录的小组成员之一。

“我记得我们曾在一间位于通往山顶的司徒拔道上现已不再存在房子的大客厅里呆过,整个客厅的地板上铺满了他的回忆录不同的章节。我会永远记住那张照片……”埃尔冈特在接受电话采访时说。

“我真的不知道他是当时重要的人物。”

“但我对他充满了极大的尊重和爱……他是一个给人留下深刻印象的人,一个有主见和尊严的人。”

埃尔冈特祥细叙述张向他“得意”地表示在1921年党第一次全国代表大会的最后一天他和他的同胞如何设法把莫斯科共产国际的代表关在会议室外。

“他很自豪的是,成立的共产党将会成为是中国人的共产党而不是成为其他人的共产党。”

但是,归根结底,埃尔冈特说,毛泽东在20世纪30年代与张的对抗中欺骗了张。

他说:“张是被胡言乱语欺骗了。”

“毛泽东就是这样的狡猾和奸诈的人,而张不应该被赋予背叛行为。”

张的妻子杨子烈在其丈夫的回忆录出版的序言中写道,她的丈夫终于决定发誓以后永不再涉及战争而且情愿在香港过着几乎穷苦的生活–但度过的是平和安宁的日子。

用张自己的话说,“我的激进思想和我的爱国热情是依旧。不过,我想与专制政权保持距离。”

“我曾经是中国舞台上的一名演员。现在我只是一个观众,我希望看到尽可能少的悲剧。”

但是,悲剧的确来了。

1968年11月,张和他的妻子离开香港前往多伦多,与他们的两个先期到达多伦多的儿子团聚。后来,他经历几次中风,之后于1979年12月3日去世。享年82岁。

《毛泽东:鲜为人知的故事》一书的作者张戎评论道“在红军初创期的时候,张一定进行过血腥清洗。”

“但他也表明悔改,在他生命的快结束的时候–他甚至改信基督教–,我认为这是一个他试图向自己过去的历史妥协告别的标志。”

(注:作者观点不代表编译者的观点)

编译自:TORONTOSTAR Asia Bureau 记者:Bill SCHILLER

The man who could have been Mao

Chang Kuo-tao, buried in a Toronto grave, was a party founding father who ended up in exile

Published On Sat Sep 26 2009

By Bill Schiller

Asia Bureau

(Chang Kuo-tao, in 1974 in Toronto, where, in his only interview, he stated: “I have washed my hands of politics.”)

It is simple, unadorned and apparently abandoned: a tombstone tucked between two shrubs in Pine Hills Cemetery in east Toronto.

But beneath this ground in section 5, plot 2263 lie the remains of a man who might have changed history.

His name is Chang Kuo-tao. He died in a Toronto nursing home in December 1979.

Unknown to most Canadians, he was once a towering political and military figure in China.

Today, some think of him as the man who might have been Mao Zedong, or more precisely: the only man who could have eclipsed Mao on his long march to power to become leader of China.

But Mao used cunning and treachery to break and banish him, according to two respected historians.

After years of living in exile in Hong Kong, Chang found his way to Canada in 1968 where he lived peacefully for the last 11 years of his life.

Yet despite the best efforts of China’s propaganda system, which relegated him to the nation’s dustbin of traitors, Chang’s legacy lives on.

As 1.3 billion Chinese prepare to celebrate their 60th anniversary as the People’s Republic next week – a celebration set to sing the glories of the ruling Communist party – the Chinese owe a debt to Chang Kuo-tao.

He was a founding father of the Communist Party of China.

He was “Chairman Chang.” He acted as the party’s top official at its first congress in Shanghai in 1921.

He was that important.

Yet no plaque commemorates Chang’s place in history in the graveyard at the corner of Birchmount Rd. and St. Clair Ave. E.

Chang might have wanted it that way. In 1974 – in the only interview he ever granted – he told a Canadian Press reporter, “I have washed my hands of politics.”

Few know he’s buried there.

His life-long wife, Young Tze Li, who died in 1994, is buried beside him.

Today, his Toronto family – two sons who preceded him to Canada, as well as his grandchildren – has receded from view.

“No one has been able to locate them,” says Kwong-Huen Choh, a retired professor of history living near Toronto who knew both Chang and his wife. But whether by accident or poetic design, Chang’s tombstone faces southeast – towards his birthplace in Pingxiang, in southern China, where his story begins.

It was from there, in the early years of the 20th century, that Chang travelled to Beijing to earn a degree at Peking University, where Mao was a lowly clerk working in the university library. It isn’t known whether the two met there.

Chang was a prominent student leader in the May 4 movement of 1919 – the famed Chinese students’ movement that sowed the early seeds of revolution – and eventually led strikes of rail and textile workers.

But it wasn’t until the 1930s, when Chang built one of the most powerful armies in China, that he emerged as the biggest threat to Mao, who had by then ascended party ranks.

Still, some believed Chang, not Mao, might lead the Communists to victory in the country’s bloody civil war and potentially usher in the new, liberated nation that was founded 60 years ago next week.

“He had solid credentials to be the leader of the Communist Party of China,” historians Jon Halliday and Jung Chang write in their 2005 bestseller, Mao: The Unknown Story.

“He was a hugely successful military commander,” says Halliday from London, “and an absolutely brilliant general – and he was just as tough as Mao.”

That would ultimately prove to be his undoing, says Halliday’s co-author and spouse Jung Chang, who says Mao had come to perceive Chang as, “his biggest threat to power.”

“Chang Kuo-tao was prepared to kill for power,” says Jung. “Mao felt that he had met someone very much like himself. As a consequence, Mao felt he absolutely had to get rid of Chang Kuo-tao.”

And so he did.

When Mao was done, he never faced a real challenger again.

Mao had strong motivation to undermine Chang: when the two met up to join forces during the Long March – the legendary Communist retreat to safety from Nationalist forces in the 1930s – Chang Kuo-tao was daunting, with an army of 80,000 soldiers.

Mao had just 10,000.

Chang welcomed Mao to their meeting point in Sichuan province much like a host would welcome a guest.

Mao knew that if he wanted to secure ultimate power and link up with their Russian sponsors ahead of Chang – winning their endorsement – he had to diminish, delay and ultimately destroy Chang’s Red Army.

“The destruction of Chang Kuo-tao militarily was critical to Mao to monopolize the Moscow connection,” says Halliday.

Mao succeeded by putting himself in a political position where he could “methodically sabotage” Chang Kuo-tao’s army at its every turn, the authors write in their meticulously researched book that took a decade to produce.

Mao schemed to ensure Chang’s forces always faced the toughest terrains and most brutal battles, says Jung – and, it seems, even attacked Chang Kuo-tao’s troops head on. Russian archives released in 2005 note that Mao once privately boasted to an envoy of Soviet strongman Josef Stalin that his forces had wiped out 30,000 of Chang’s soldiers.

“That was a stunning revelation,” says Halliday.

In the end Mao prevailed. His envoy made it to Moscow where Pravda then proclaimed Mao as the “new leader of the Chinese people.”

Chang would hang on, but finally fled to the opposition Nationalists in 1938, seeking refuge later in the British colony of Hong Kong.

“He wasn’t as shrewd as Mao politically,” Halliday observes. “In the end he allowed himself to be outfoxed by him.”

Had Chang won power, Chinese history might have been different, says Halliday.

Calamities that scarred China under Mao, might have been avoided.

“I don’t think Chang Kuo-tao would have launched anything like the Cultural Revolution,” he says, referring to the violent and chaotic decade from 1966 until 1976 during which Mao encouraged Chinese youth to overturn and destroy almost everything that was precious and traditional in Chinese society.

“Nor do I think he would have presided over the great famine either.”

The Chinese famine of the late 1950s, the greatest in recorded history, claimed as many as 38 million lives as Mao’s cadres worked starving Chinese peasants to death.

“That required a certain heartlessness,” says Halliday.

His and Jung’s book notes that Chang carried out his own bloody purges at the peak of his military career. But neither believes he was capable of monumental devastation on the Mao scale.

Once Chang defected, party propagandists spread the story – real or imagined – that Chang had plotted to sabotage and kill Mao.

True or not, in some circles it stuck. In Shanghai, at the museum of the First National Congress of the Communist Party of China, Chang’s seminal role in party history is recognized – but dismissed. He is branded a traitor, expelled for having “engaged in the activities of splitting the party and the Red Army during the Long March …”

Mao, on the other hand, shines.

In a recreation of the historic 1921 meeting dramatized by stolid life-size figures, Mao holds forth with a beatific glow, as the central figure standing at a rustic table, addressing the upturned faces of 12 Chinese apostles and two agents from Communist International.

Chang is not at the table; he is in fact outside the circle and the only figure with his arms folded defiantly as Mao speaks.

But even the museum guards don’t buy the propaganda.

“If it were based on historical fact Chang Kuo-tao should be in the centre,” one says, at a recent afternoon visit. “But that wouldn’t have been approved. With Mao at the centre though, it was approved.

“Later Chang became a traitor, so you really couldn’t put him in that position.”

Says another, “It’s the victors who get to write history.”

But outside the museum visitor Li Xiao Fang, an architectural engineer, isn’t sold on the fact that Chang was a traitor.

“We don’t really consider him as such … we just think he thought differently,” she says.

“We don’t only believe what the textbooks taught us. Today, we think more rationally. This was an inner-party struggle.”

She’s surprised to learn that Chang is buried in Canada.

“We just thought he died.”

But Chang lived on.

And in Hong Kong he began to write his memoirs.

American-born writer Robert Elegant, 81 and now living in Italy, remembers the period vividly.

Elegant was part of a small group of people helping Chang with an English translation of his memoirs in the early 1950s.

“I remember we had a large living room in a house that no longer exists on Stubbs Rd. on the way to The Peak and the entire living room floor was covered with different chapters of it. I’ll always remember that picture …” Elegant says in a telephone interview.

“I really didn’t know at the time what a major figure he was.

“But I had a great deal of respect and affection for him … He was an impressive figure, a man of substance and dignity.”

Elegant recounts how Chang told him with “glee” how he and his compatriots managed to shut out the Moscow representatives of Communist International from the final day of the 1921 meetings.

“He was quite proud that the party was going to be Chinese and nothing else.”

In the end however, Elegant says Mao deceived Chang in their 1930s confrontation.

“He was flimflammed,” he says.

“Mao was such a cunning and treacherous man. And Chang wasn’t given to treachery.”

In a forward to an edition of her husband’s memoirs, wife Young Tze Li wrote that her husband had finally decided to swear off war and was content to live in near-poverty in Hong Kong – but at peace.

“In his own words, ‘My radical thinking and my patriotic enthusiasm are the same as ever. But I wish to keep my distance from autocratic regimes.’ ”

“‘I used to be an actor on the stage of China. Now I’m only a member of the audience, and I hope to see as few tragedies as possible.’ ”

But the tragedies did come.

In November 1968, Chang and his wife left Hong Kong for Toronto, to be reunited with their two sons who had preceded them. Later he suffered several strokes and died on Dec. 3, 1979. He was 82.

“In an earlier time, he certainly carried out bloody purges,” remarks author Jung Chang.

“But he also showed repentance and even converted to Christianity at the end of his life – a sign, I think, that he was trying to come to terms with his past.”

http://www.thestar.com/news/world/article/701359

相关文章:

1 Comment

Leave a Comment

要发表评论,您必须先登录。

滚滚长江东逝水,浪花淘尽英雄。是非成败转头空,青山依旧在,几度夕阳红。 白发渔樵江渚上,惯看秋月春风。一壶浊酒喜相逢。古今多少事,都付笑谈中。