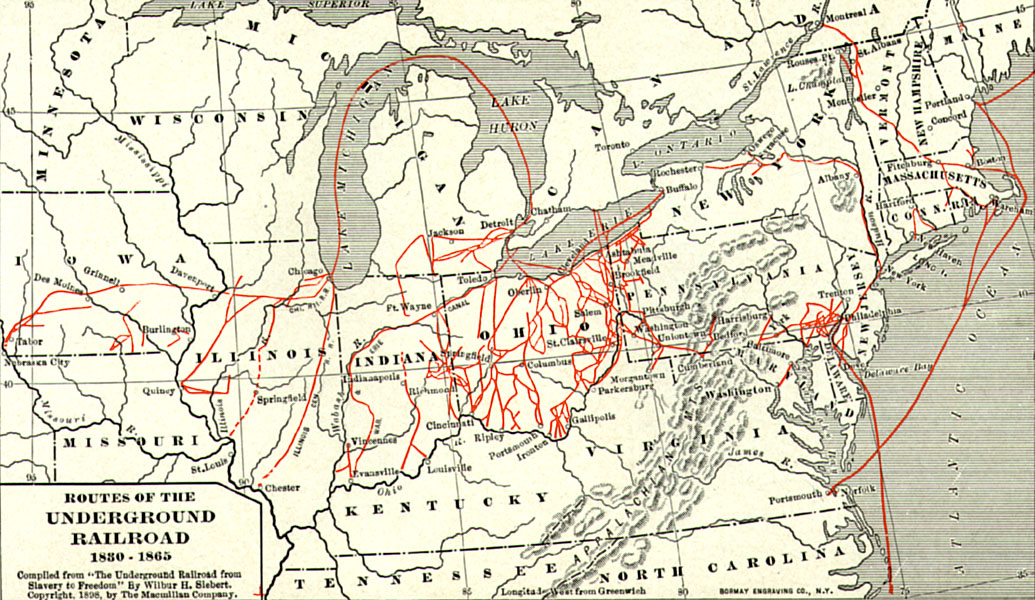

捷克佳/收到一则来自安省政府的新闻简讯,在黑人历史纪念月期间,省府要员专程去哈密尔顿出席一个纪念匾额的揭幕仪式,内容涉及哈密尔顿的地下铁路。哈密尔顿,黑人,地下铁路,似乎彼此并不关联,查阅史料方知,这所谓的“地下铁路”并非真正的铁路,而是借用相关的交通术语,指在美国南北战争前,南方黑奴经由秘密通道前往北方的秘密通道,期间,其中至少3万黑人逃至加拿大,最大的群体居住在多伦多-温莎-尼亚加拉瀑布所构成的三角区内。这是一段美洲黑人的迁徙史。一则简讯算是为自己补了一段历史课。

安省政府新闻稿/(安省咸美顿市2月15日讯)为庆祝2008年黑人历史月,昨天上午(2月15日),安省公民及移民厅厅长陈国治与文化厅长卡萝Aileen Carroll专程到咸美顿市出席纪念匾额揭幕仪式。陈国治表示:“在两百年前的黑奴解放运动中,咸美顿的地下铁路扮演了一个非常重要的角色,它帮助黑人逃脱,展开自由新生活。如今,透过这些无名英雄的历史故事,我们学会要珍惜自由的可贵,进而一起努力,共创美好的安省,让每个人有机会在此发挥他们的潜力。”他同时以在场的前安省省督,现任安省文化遗产信托基金(Ontario Heritage Trust)主席亚历山大Lincoln Alexander为例,赞扬黑人对安省的贡献。

图安省公民及移民厅厅长陈国治为匾额揭幕仪式致词时,(左起)文化厅长卡萝Aileen Carroll、前安省省督亚历山大Lincoln Alexander与司仪Annette Mann专心聆听。

Underground Railroad

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Underground Railroad was an informal network of secret routes and safe houses used by 19th century Black slaves in the United States to escape to free states (or as far north as Canada) with the aid of abolitionists who were sympathetic to their cause.[1] The term is also applied to the abolitionists who aided the fugitives.[2] Other routes led to Mexico or overseas.[3] The Underground Railroad was at its height between 1810 and 1850.[4] One report estimates that up to 100,000 people escaped enslavement via the Underground Railroad.[2], but census figures only account for 6,000.[5]

Contents

1 Structure

2 Route

2.1 Traveling conditions

2.2 Terminology

3 Folklore

4 Legal and political

5 Arrival in Canada

6 Notable people

7 Notable locations

8 Contemporary literature

9 Related events

10 See also

11 References

12 Further reading

13 External links

Structure

The escape network of The Underground Railroad was not literally subterranean, but rather “underground” in the sense of underground resistance. The network was known as a “railroad” by way of the use of rail terminology in the code. The Underground Railroad consisted of meeting points, secret routes, transportation, and safe houses, and assistance provided by abolitionist sympathizers. Individuals were often organized in small, independent groups, which helped to maintain secrecy since some knew of connecting “stations” along the route but few details of their immediate area. Escaped slaves would move along the route from one way station to the next, steadily making their way north. “Conductors” on the railroad came from various backgrounds and included free-born blacks, white abolitionists, former slaves (either escaped or manumitted), and Native Americans. Churches also often played a role, especially the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), Congregationalists, Wesleyans, and Reformed Presbyterians as well as certain sects of mainstream denominations such as branches of the Methodist church and American Baptists.

Route

Many people associated with the Underground Railroad only knew their part of the operation and not of the whole scheme. Though this may seem like an unreliable route for slaves to gain their freedom, hundreds of slaves obtained freedom to the North every year.

The resting spots where the runaways could sleep and eat were given the code names “stations” and “depots” which were held by “station masters”. There were also those known as “stockholders” who gave money or supplies for assistance. There were the “conductors” who ultimately moved the runaways from station to station. The “conductor” would sometimes act as if he or she were a slave and enter a plantation. Once a part of a plantation the “conductor” would direct the fugitives to the North. During the night the slaves would move, traveling on about 10–20 miles (15–30 km) per night. They would stop at the so-called “stations” or “depots” during the day and rest. While resting at one station, a message was sent to the next station to let the station master know the runaways were on their way. Sometimes boats or trains would be used for transportation. Money was donated by many people to help buy tickets and even clothing for the fugitives so they would remain unnoticeable. Soon after the railroad had freed 300 slaves, some of the freed slaves made a store for the railroad.

Some people — most of them, naturally, pro-slavery Southerners — were upset by this whole process. Resulting from many efforts to fix this ostensible problem, a law was passed that allowed slave owners to hire people to catch their runaways and arrest them. The fugitive slave laws became a problem because many legally freed slaves were being arrested as well as the fugitives. This then encouraged more people of the North to become a part of the Underground Railroad. Often, “bounty hunters” would abduct free blacks, and sell them into slavery.

Traveling conditions

Although the fugitives sometimes traveled on real railways, the primary means of transportation were on foot or by wagon.

In addition, routes were often purposely indirect in order to throw off pursuers. Most escapes were by individuals or small groups; occasionally, such as with the Pearl Rescue, there were mass escapes. The majority of the escapees are believed to have been male field workers younger than 40 years old. The journey was often too arduous and treacherous for women or children to complete. Many fugitive bondsmen, however, who escaped via the Railroad and established livelihoods as free men, later purchased their wives, children, and other family members out of slavery. Because of this, the number of former slaves who owed their freedom at least in part to the courage and determination of those who operated the Underground Railroad was greater than the many thousands who actually traveled its secret routes.

Due to the risk of discovery, information about routes and safe havens was passed along by word of mouth. Southern newspapers of the day were often filled with pages of notices soliciting information about escaped slaves and offering sizable rewards for their capture and return. Federal marshals and professional bounty hunters known as slave catchers pursued fugitives as far as the Canadian border.

The risk of capture was not limited solely to actual fugitives. Because strong, healthy blacks in their prime working and reproductive years were highly valuable commodities, it was not unusual for free blacks — both freedmen (former slaves) and those who had lived their entire lives in freedom — to be kidnapped and sold into slavery. “Certificates of freedom” — signed, notarized statements attesting to the free status of individual blacks — could easily be destroyed and thus afforded their owners little protection. Moreover, under the terms of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, when suspected fugitives were seized and brought to a special magistrate known as a commissioner, they had no right to a jury trial and could not testify in their own behalf; the marshal or private slave-catcher only needed to swear an oath to acquire a writ of replevin, for the return of property.

Nevertheless, Congress believed the fugitive slave laws were necessary because of the lack of cooperation by the police, courts, and public outside of the Deep South. States such as Michigan passed laws interfering with the federal bounty system, which politicians from the South felt was grossly inadequate, and this became a key motivation for secession. In some parts of the North slave-catchers needed police protection to carry out their federal authority. Even in states that resisted cooperation with slavery laws, though, blacks were often unwelcome; Indiana passed a constitutional amendment that barred blacks from settling in that state.

Terminology

Members of The Underground Railroad often used specific jargon, based on the metaphor of the railway. For example:

-People who helped slaves find the railroad were “agents” (or “shepherds”)

-Guides were known as “conductors”

-Hiding places were “stations”

-Abolitionists would fix the “tracks”

-“Stationmasters” hid slaves in their homes

-Escaped slaves were referred to as “passengers” or “cargo”

-Slaves would obtain a “ticket”

-Just as in common gospel lore, the “wheels would keep on turning”

-Financial benefactors of the Railroad were known as “stockholders”.

As well, the Big Dipper asterism, whose “bowl” points to the north star, was known as the drinkin’ gourd, and immortalized in a contemporary code tune. The Railroad itself was often known as the “freedom train” or “Gospel train”, which headed towards “Heaven” or “the Promised Land”—Canada.

William Still, often called “The Father of the Underground Railroad”, helped hundreds of slaves to escape (as many as 60 a month), sometimes hiding them in his Philadelphia home. He kept careful records, including short biographies of the people, that contained frequent railway metaphors. He maintained correspondence with many of them, often acting as a middleman in communications between escaped slaves and those left behind. He then published these accounts in the book The Underground Railroad in 1872.

According to Still, messages were often encoded so that messages could only be understood by those active in the railroad. For example, the following message, “I have sent via at two o’clock four large and two small hams”, indicated that four adults and two children were sent by train from Harrisburg to Philadelphia. However, the additional word via indicated that the “passengers” were not sent on the usual train, but rather via Reading, Pennsylvania. In this case, authorities were tricked into going to the regular train station in an attempt to intercept the runaways, while Still was able to meet them at the correct station and guide them to safety, where they eventually escaped to Canada.

Folklore

Main article: Quilts of the Underground Railroad

Since the 1980s, claims have arisen that quilt designs were used to signal and direct slaves to escape routes and assistance. The quilt design theory is disputed. The first published work documenting an oral history source was in 1999 and the first publishing is believed to be a 1980 children’s book[6], so it is difficult to evaluate the veracity of these claims, which are not accepted by quilt historians.[citation needed] There is no contemporary evidence of any sort of quilt code, and quilt historians such as Pat Cummings and Barbara Brackman have raised serious questions about the idea. In addition, Underground Railroad historian Giles Wright has published a pamphlet debunking the quilt code.[citation needed]

Many accounts also mention spirituals and other songs that contained coded information intended to help navigate the railroad.[citation needed] Songs such as “Steal Away” and other field songs were often passed down purely orally, and others, like “Follow the Drinking Gourd,” were published after the days of the Railroad.[6] Tracing their origins and meanings is difficult.[citation needed] In any case, many African-American songs of the period deal with themes of freedom and escape, and distinguishing coded information from expression and sentiment may not be possible.

Legal and political

When frictions between North and South culminated in the American Civil War, many blacks, slave and free, fought with the Union Army. Following passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, in some cases the Underground Railroad operated in reverse as fugitives returned to the United States.

Arrival in Canada

Estimates vary widely, but at least 30,000 slaves, some saying more than 100,000, escaped to Canada via the Underground Railroad.[7] The largest group settled in Upper Canada (called Canada West from 1841, and today southern Ontario), where numerous African Canadian communities developed. These were generally in the triangular region bounded by Toronto, Niagara Falls, and Windsor. Nearly 1,000 refugees settled in Toronto, and several rural villages made up mostly of ex-slaves were established in Chatham-Kent and Essex County.

Important black settlements also developed in more distant British colonies (now parts of Canada). These included Nova Scotia, Lower Canada (present-day Quebec), as well as Vancouver Island, where Governor James Douglas encouraged black immigration because of his opposition to slavery and because he hoped a significant black community would form a bulwark against those who wished to unite the island with the United States.

Upon arriving at their destinations, many fugitives were disappointed. While the British colonies had no slavery, discrimination was still common. Many of the new arrivals had great difficulty finding jobs, in part because of mass European immigration at the time, and overt racism was common.

With the outbreak of the Civil War in the United States, many black refugees enlisted in the Union Army and, while some later returned to Canada, many remained in the United States. Thousands of others returned to the American South after the war ended. The desire to reconnect with friends and family was strong, and most were hopeful about the changes emancipation and Reconstruction would bring.

Notable people

Dr. Anderson Ruffin Abbott

John Brown

Levi Coffin

Calvin Fairbank

Thomas Garrett

William Lloyd Garrison

Josiah Bushnell Grinnell

Josiah Henson

James Butler (“Wild Bill”) Hickok

Isaac Hopper

John Parker

John Wesley Posey

Samuel Seawell

William Still

Harriet Tubman – made 19 trips back to the South and helped free over 300 people

Charles Augustus Wheaton

Frederick Douglass

Sojourner Truth

Notable locations

Bialystoker Synagogue

Boston, Massachusetts

Buffalo, New York

Burkle Estate, Tennessee

Burlington, Wisconsin

Chatham-Kent, Ontario

Chicago, Illinois

Cincinnati, Ohio

Cyrus Gates Farmstead

Detroit, Michigan

Dresden, Ontario

Elmira, NY

Farmington, Connecticut

Jacksonville, Illinois

Lawnside, New Jersey

Lewis, Iowa

Mayhew Cabin

Milton, Wisconsin

Nebraska City, Nebraska

Oberlin, Ohio

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Ripley, Ohio

Salem, Ohio

Sandusky, Ohio

Sandy Ground – Staten Island, New York

St. Catharines, Onatrio

Westfield, Indiana

Wilmington, Delaware

Windsor, Ontario

Contemporary literature

1829 Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World by David Walker (a call for resistance to slavery in Georgia)

1832 The Planter’s Northern Bride by Caroline Lee Hentz

1852 Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe

Related events

1776 – Declaration of Independence

1820 – Missouri Compromise

1850 – Compromise of 1850

1850 – Fugitive Slave Act

1854 – Kansas-Nebraska Act

1857 – Dred Scott Decision

1858 – Oberlin-Wellington Rescue

1860 – Abraham Lincoln of Illinois elected the first Republican U.S. President

1861 through 1865 – American Civil War

1863 – Emancipation Proclamation issued by President Lincoln

1865 – Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

…………

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Underground_railroad

People & Events

The Underground Railroad

c.1780 – 1862

The Underground Railroad, a vast network of people who helped fugitive slaves escape to the North and to Canada, was not run by any single organization or person. Rather, it consisted of many individuals — many whites but predominently black — who knew only of the local efforts to aid fugitives and not of the overall operation. Still, it effectively moved hundreds of slaves northward each year — according to one estimate, the South lost 100,000 slaves between 1810 and 1850.

An organized system to assist runaway slaves seems to have begun towards the end of the 18th century. In 1786 George Washington complained about how one of his runaway slaves was helped by a “society of Quakers, formed for such purposes.” The system grew, and around 1831 it was dubbed “The Underground Railroad,” after the then emerging steam railroads. The system even used terms used in railroading: the homes and businesses where fugitives would rest and eat were called “stations” and “depots” and were run by “stationmasters,” those who contributed money or goods were “stockholders,” and the “conductor” was responsible for moving fugitives from one station to the next.

For the slave, running away to the North was anything but easy. The first step was to escape from the slaveholder. For many slaves, this meant relying on his or her own resources. Sometimes a “conductor,” posing as a slave, would enter a plantation and then guide the runaways northward. The fugitives would move at night. They would generally travel between 10 and 20 miles to the next station, where they would rest and eat, hiding in barns and other out-of-the-way places. While they waited, a message would be sent to the next station to alert its stationmaster.

The fugitives would also travel by train and boat — conveyances that sometimes had to be paid for. Money was also needed to improve the appearance of the runaways — a black man, woman, or child in tattered clothes would invariably attract suspicious eyes. This money was donated by individuals and also raised by various groups, including vigilance committees.

Vigilance committees sprang up in the larger towns and cities of the North, most prominently in New York, Philadelphia, and Boston. In addition to soliciting money, the organizations provided food, lodging and money, and helped the fugitives settle into a community by helping them find jobs and providing letters of recommendation.

The Underground Railroad had many notable participants, including John Fairfield in Ohio, the son of a slaveholding family, who made many daring rescues, Levi Coffin, a Quaker who assisted more than 3,000 slaves, and Harriet Tubman, who made 19 trips into the South and escorted over 300 slaves to freedom.

Related Entries:

? Levi Coffin’s Underground Railroad station

? Fugitives Arriving at Indiana Farm

? Harriet Tubman

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4p2944.html

Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was the name given to the system by which escaped slaves from the South were helped in their flight to the North. It is believed that the system started in 1787 when Isaac T. Hopper, a Quaker, began to organize a system for hiding and aiding fugitive slaves. Opponents of slavery allowed their homes, called stations, to be used as places where escaped slaves were provided with food, shelter and money. The various routes went through 14 Northern states and Canada. It is estimated that by 1850 around 3,000 people worked on the underground railroad. Some of the most best known of the people who provided help on the route included William Still, Gerrit Smith, Salmon Chase, David Ruggle, Thomas Garrett, William Purvis, Jane Grey Swisshelm, William Wells Brown, Frederick Douglass, Henry David Thoreau, Lucretia Mott, Charles Langston, Levi Coffin and Susan B. Anthony.

The underground railroad also had people known as conductors who went to the south and helped guide slaves to safety. One of the most important of these was the former slave, Harriet Tubman. She made 19 secret trips to the South, during which she led more than 300 slaves to freedom. Tubman was considered such a threat to the slave system that plantation owners offered a $40,000 reward for her capture.

Stations were usually about twenty miles apart. Conductors used covered wagons or carts with false bottoms to carry slaves from one station to another. Runaway slaves usually hid during the day and travelled at night. Some of those involved notified runaways of their stations by brightly lit candles in a window or by lanterns positioned in the frontyard. By the middle of the 19th century it was estimated that over 50,000 slaves had escaped from the South using the underground railroad.

Plantation owners became concerned at the large number of slaves escaping to the North and in 1850 managed to persuade Congress to pass the Fugitive Slave Act. In future, any federal marshal who did not arrest an alleged runaway slave could be fined $1,000. Any person aiding a runaway slave by providing shelter, food or any other form of assistance was liable to six months’ imprisonment and a $1,000 fine.

The Fugitive Slave Act failed to stop the underground railroad. Thomas Garrett, the Deleware station-master, paid more than $8,000 in fines and Calvin Fairbank served over seventeen years in prison for his anti-slavery activities. Whereas John Fairfield, one of the best known of the white conductors, was killed working for the underground railroad.

http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/USASunderground.htm

Underground Railroad–The Journey

You are a slave.

Your body, your time, your very breath belong to a farmer in 1850s Maryland. Six long days a week you tend his fields and make him rich. You have never tasted freedom. You never expect to.

And yet . . . your soul lights up when you hear whispers of attempted escape. Freedom means a hard, dangerous trek. Do you try it?

“Moses” is coming! You’ve heard the stories about her. She is Harriet Tubman, a former slave who ran away from a nearby plantation in 1849 but returns to rescue others. Guided by her “visions,” she has never lost a passenger. Even if Moses can’t fit you into her next group, she’ll tell you how to follow the North Star to freedom in Canada.

Every step seems louder. Twigs snap, leaves crackle. But you walk on, till you see a group of friendly faces. You join them shyly and meet “General Tubman” herself. She tells you how to sneak across the bridge over the Choptank River and where to find friends in a place called Delaware.

Your head says go, your feet say no. Harriet Tubman told you that a lantern on a hitching post means a safe house. But can you really knock on a white family’s door and trust them to help you?

A warm welcome and hot food—that’s what you find inside the house. Guided by their conscience, the owners break the law by helping runaways. Yet terror still haunts you. As you fall asleep you hear bloodhounds not far away. They are looking for fugitives, looking for you. Freedom is still a long way off.

You’ve never seen a city like Wilmington—the people, the streets, the houses, the noise! Now you know the plantation really is hundreds of miles away. Your host, a Quaker businessman named Thomas Garrett, smiles gently and promises you’ll see much bigger cities before you reach Canada.

A good friend of Tubman’s, Garrett has worked on The Underground Railroad for almost 40 years. A few years ago he was arrested and fined $5,400. It didn’t stop him for a minute.

You’ve never met a man like this—not a black man, anyway. Born free, William Still is a successful, confident merchant and a leader in the fight against slavery. He can read and write—skills denied you—and takes careful notes about your journey. Watching your deep, joyous breaths of the free air of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, he cautions you not to get giddy. You’ve reached a free state, it’s true, but United States law still sees you as your master’s property, and bounty hunters are everywhere. He helps you get ready for another long stretch of travel.

Weeks of trudging, including a grueling passage of almost 250 miles (402 kilometers) through the Appalachian Mountains, have brought you to Rochester. Perhaps you’ll catch a glimpse of fugitive Frederick Douglass, the fiery orator who publishes the North Star, an abolitionist paper. You meet with another noted citizen, activist Susan B. Anthony. She and her antislavery friends give you warm clothing for the hard Canadian climate and make sure you’re taken safely to Lake Erie.

Across Lake Erie lies Canada—and freedom. A few weeks earlier you might have coaxed an easy ride from a sympathetic ferry captain. But as winter takes hold, chunks of ice have begun to form. You might find someone to row you across, or you could try leaping from one ice floe to another. Either way, you’ll be freezing cold. Yet staying exposes you—and your helpers—to slave hunters. Do you try going across?

You made it! It took courage, luck, help, and incredible stamina. Here in Canada, you can finally breathe free. Not only won’t the government return you to slavery in the United States, but you can vote and even own land. No wonder thousands have already run away to settle here. You still face challenges: finding a home, making a living, adjusting to a new place. But you face them in freedom.

http://www.nationalgeographic.com/railroad/j1.html

Time Line

1501—African Slaves in the New World

Spanish settlers bring slaves from Africa to Santo Domingo (now the capital of the Dominican Republic).

1522—Slave Revolt: the Caribbean

Slaves rebel on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, which now comprises Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

1562—Britain Joins Slave Trade

John Hawkins, the first Briton to take part in the slave trade, makes a huge profit hauling human cargo from Africa to Hispaniola.

1581—Slaves in Florida

Spanish residents in St. Augustine, the first permanent settlement in Florida, import African slaves.

1619—Slaves in Virginia

Africans brought to Jamestown are the first slaves imported into Britain’s North American colonies. Like indentured servants, they were probably freed after a fixed period of service.

1662—Hereditary Slavery

Virginia law decrees that children of black mothers “shall be bond or free according to the condition of the mother.”

1705—Slaves as Property

Describing slaves as real estate, Virginia lawmakers allow owners to bequeath their slaves. The same law allowed masters to “kill and destroy” runaways.

1712—Slave Revolt: New York

Slaves in New York City kill whites during an uprising, later squelched by the militia. Nineteen rebels are executed.

1739—Slave Revolt: South Carolina

Crying “Liberty!” some 75 slaves in South Carolina steal weapons and flee toward freedom in Florida (then under Spanish rule). Crushed by the South Carolina militia, the revolt results in the deaths of 40 blacks and 20 whites.

1775—American Revolution Begins

Battles at the Massachusetts towns of Lexington and Concord on April 19 spark the war for American independence from Britain.

1775—Abolitionist Society

Anthony Benezet of Philadelphia founds the world’s first abolitionist society. Benjamin Franklin becomes its president in 1787.

1776—Declaration of Independence

The Continental Congress asserts “that these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States”.

1783—American Revolution Ends

Britain and the infant United States sign the Peace of Paris treaty.

1784—Abolition Effort

Congress narrowly defeats Thomas Jefferson’s proposal to ban slavery in new territories after 1800.

1790—First United States Census

Nearly 700,000 slaves live and toil in a nation of 3.9 million people.

1793—Fugitive Slave Act

The United States outlaws any efforts to impede the capture of runaway slaves.

1794—Cotton Gin

Eli Whitney patents his device for pulling seeds from cotton. The invention turns cotton into the cash crop of the American South—and creates a huge demand for slave labor.

1808—United States Bans Slave Trade

Importing African slaves is outlawed, but smuggling continues.

1820—Missouri Compromise

Missouri is admitted to the Union as a slave state, Maine as a free state. Slavery is forbidden in any subsequent territories north of latitude 36°30?.

1822—Slave Revolt: South Carolina

Freed slave Denmark Vesey attempts a rebellion in Charleston. Thirty-five participants in the ill-fated uprising are hanged.

1831—Slave Revolt: Virginia

Slave preacher Nat Turner leads a two-day uprising against whites, killing about 60. Militiamen crush the revolt then spend two months searching for Turner, who is eventually caught and hanged. Enraged Southerners impose harsher restrictions on their slaves.

1835—Censorship

Southern states expel abolitionists and forbid the mailing of antislavery propaganda.

1846-48—Mexican-American War

Defeated, Mexico yields an enormous amount of territory to the United States. Americans then wrestle with a controversial topic: Is slavery permitted in the new lands?

1847—Frederick Douglass’s Newspaper

Escaped slave Frederick Douglass begins publishing the North Star in Rochester, New York.

1849—Harriet Tubman Escapes

After fleeing slavery, Tubman returns south at least 15 times to help rescue several hundred others.

1850—Compromise of 1850

In exchange for California’s entering the Union as a free state, northern congressmen accept a harsher Fugitive Slave Act.

1852—Uncle Tom’s Cabin Published

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel about the horrors of slavery sells 300,000 copies within a year of publication.

1854—Kansas-Nebraska Act

Setting aside the Missouri Compromise of 1820, Congress allows these two new territories to choose whether to allow slavery. Violent clashes erupt.

1857—Dred Scott Decision

The United States Supreme Court decides, seven to two, that blacks can never be citizens and that Congress has no authority to outlaw slavery in any territory.

1860—Abraham Lincoln Elected

Abraham Lincoln of Illinois becomes the first Republican to win the United States Presidency.

1860—Southern Secession

South Carolina secedes in December. More states follow the next year.

1861-65—United States Civil War

Four years of brutal conflict claim 623,000 lives.

1863—Emancipation Proclamation

President Abraham Lincoln decrees that all slaves in Rebel territory are free on January 1, 1863.

1865—Slavery Abolished

The 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution outlaws slavery.

http://www.nationalgeographic.com/railroad/tl.html

William Still

William Still, one of seventeen children, was born in Burlington County in 1821. His father escaped to New Jersey and was later followed by his wife and children.

Still left New Jersey for Philadelphia in 1844. Three years later he was appointed secretary of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society. Still was the first black man to join the society and was able to provide first-hand experience of what it was like to be a slave.

Still, who established a profitable coal business in Philadelphia, used his house as one of the stations on the Underground Railroad. Still interviewed the fugitives and kept careful records of each so that family and friends might locate them. According to his records, Still helped 649 slaves receive their freedom.

After John Brown and his insurrection at Harper’s Ferry failed in 1859 Still sheltered some of his men and helped them escape capture.

At this time Still began his campaign to end racial discrimination on Philadelphia streetcars. He wrote an account of this campaign in Struggle for the Civil Rights of the Coloured People of Philadelphia in the City Railway Cars (1867). He followed this with The Underground Railroad (1872) and Voting and Laboring (1874).

Still established an orphanage for the children of African-American soldiers and sailors. Other charitable work included the founding of a Mission Sabbath School and working with the Young Men’s Christian Association. William Still died in Philadelphia on 14th July, 1902.

http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/USASstill.htm

哈丽雅特·塔布曼 (Harriet Tubman)

“地下铁道”领导人

(生于1820年左右;卒于1913年3月10日)

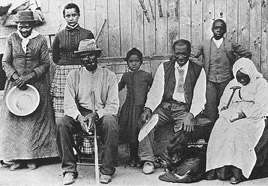

哈丽雅特·塔布曼(左一)在南北战争爆发前担任”地下铁道”侦察员,以其超群的才智帮助300名奴隶获得自由。(Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

保罗·柯林斯的绘画作品,描绘哈丽雅特·塔布曼的”地下铁道”。(Frederik Meijer赠品,藏于Grand Rapids公共博物馆)

哈丽雅特·塔布曼出生在马里兰州多切斯特郡的一个奴隶家庭。这位非凡的非洲裔女性勇敢地逃往宾夕法尼亚州费城的一个安全之地,使自己摆脱了奴役。1850年颁布的《逃亡奴隶法》(Fugitive Slave Act)将帮助逃亡奴隶的行为定为非法,促使塔布曼决定参加由帮助奴隶获得自由的人建立的被称为”地下铁道”(Underground Railroad)的网络。

所谓的”地下铁道”既不在地下,也不是铁道,而是由废奴主义者和过去的奴隶用一系列房屋、地道和道路精心筑成的秘密通道,帮助奴隶逃离他们备受压迫的南方。哈丽雅特对这些通道了如指掌,她从未被抓到过,并总是成功地把她的”乘客”送往安全之地。

在南北战争前她成功地护送300名奴隶通过”地下铁道”走向自由。塔布曼曾先后19次冒险前往实施奴隶制的地区。其中一次,她救出了自己70岁的年迈父母,把他们送往纽约州的奥本。于是,奥本也成了她的家。1860年,她开始频繁地前往各地发表演说,不仅呼吁废除奴隶制,而且要求重新确定妇女的权利。

1861年南北战争爆发后,她为联邦政府的军队当过护士、密探和侦察员。由于她在”地下铁道”担任”列车员”的多年经历,她对乡村地区特别熟悉,因此被视作一名具有非凡价值的侦察员。

由于政府办事效率低下,也许还因为种族歧视的残留,塔布曼在战争结束后未能获得政府的养老金,因此在很多年中,她在经济上十分拮据。她努力推动妇女和黑人地位的提高,要求为孤儿和穷困的老人提供栖身之地。她最终从美国陆军获得了一笔数额很小的养老金,1908年,她将自己的大部份养老金用于建造一座木房子,收容奥本地区的老人和穷人。她在这个收容所里服务,她本人于1913年去世前的最后几年里也在这个收容所里得到照顾。

http://usinfo.state.gov/mgck/home/products/publications/womeninfln/tubman.htm

AMERICAN MOSAIC – National Underground Railroad Freedom Center

By Jerilyn Watson, Nancy Steinbach and Caty Weaver

Broadcast: August 20, 2004

(MUSIC)

HOST:

Welcome to AMERICAN MOSAIC, in VOA Special English.

(MUSIC)

National Underground Railroad Freedom Center

HOST:

The National Underground Railroad Freedom Center.

(Picture – Cincyusa.com)

The new National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati, Ohio officially opens on August twenty-third. The name sounds as if it tells about a real railroad. But the underground railroad was a secret organization. It helped African American slaves escape their owners during the eighteen hundreds. The slaves and the people who helped them flee formed the underground railroad system.Shep O’Neal has more.

ANNCR:

The National Underground Railroad Freedom Center is a special museum. The Freedom Center is on the north side of the Ohio River. That is part of an area that meant hope for slaves trying to escape. It was called the “freedom corridor.” People fleeing their owners could stand on the other side of the river and dream of freedom across the water.

The Freedom Center cost one hundred ten million dollars to build. Its collection shows two hundred objects. These include a copy of a wagon with a false bottom that was used to hide fleeing slaves. There are also photographs of Americans who were activists against slavery.

Visitors can also see objects from the Civil War. The southern states fought the northern states from eighteen sixty-one to eighteen sixty-five. In eighteen sixty-three, President Abraham Lincoln announced an order to free the slaves.

Perhaps the center’s most interesting object is a small building where slaves were kept. This wooden “pen” stands two levels high. A slave trader built it in the eighteen thirties. People captured in Africa were temporarily forced to stay inside the pen. Then they were sold for service in places further south. The slave pen was found on a farm in the state of Kentucky. The owner of the farm gave it to the Freedom Center. Experts spent six years researching the history of the building.

Television star Oprah Winfrey introduces one of the films shown at the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center. Actors tell about a young woman who escapes slavery. She flees to a town called Ripley, Ohio. Her former owners try to recapture her. But a family active in the Underground Railroad helps her remain free.

The National Underground Railroad Freedom Center will offer a number of educational programs.

They include public speakers. Also, the center will provide programs for visiting school groups and information for students through an Internet Web site. It is www.freedomcenter.org.

(MUSIC)

HOST:

This is Doug Johnson.

I hope you enjoyed AMERICAN MOSAIC. Join us again next week for VOA’s radio magazine in Special English.

This program was written by Nancy Steinbach, Jerilyn Watson and Caty Weaver. Paul Thompson was the producer.

Underground Railroad的故事

作者: 老七 注册 | 06/28/2006, 16:02:21 | 作者档案 | 修改 | 回复 | 枫华茶园首页

南安省大名鼎鼎的所谓的“地下铁路”,原本却不是甚么铁路。

这是十九世纪中期、美国南北战争前的事。

进入国家地理网站的“Underground Railroad”一页,你能看到这么几行字:

“你是个奴隶。

你的身体,你的时间,你自己的呼吸,统统属于一个十九世纪五十年代的马里兰农场主。一个个漫长的日子里,你一直在耕作他的土地,使他富足。你从没尝到过自由的味道,你甚至从没期待过自由。

正当此时,你的耳边响起了一声悄语,你的心底闪过了一丝光亮:

--逃出去。

自由,意味着艰苦而又凶险的跋涉。你要试试吗?”

点击“YES”,你就可以在你的屏幕上体验一下那个一百多年前的“underground railroad”。

这条地下铁路的终点,是南安省的一个小镇,叫Chatham。

在镇子的南面,有一片九千英亩大小的移民点,叫Buxton。现在它是加拿大的国立博物馆。一八四九年,一个名字叫威廉·金的加拿大牧师,带着他刚刚从故去的岳父那里继承的十五名奴隶来到这里。金牧师在这里建了学校和教堂,过去的黑奴们可以耕种自己的土地,可以上学,可以结婚,甚至可以投票选举。他们的后代再不是奴隶。

金牧师的奴隶们,还有在他们前后逃到南安省的黑奴,便是最早的一批非裔加拿大人。

当年在美国,帮助奴隶逃跑是犯法的。即便是在没有奴隶的北方州如宾夕法尼亚,奴隶主们、还有那些专门追猎逃奴的人,照样可以把逃亡奴隶抓回去。

而在当时的英属北美--加拿大,奴隶制是不被承认的。但这并不意味着威廉牧师和他的同伙们能够成为加拿大的英雄。

随着逃亡到Buxton的黑人陆续到来,周围的白人开始愤怒了。他们状告金牧师,企图限制定居点的开发。不单如此,到后来,就连金牧师的生命都受到了威胁。

可是金牧师的作为也得到了很多加拿大人的支持。加拿大独立的功臣之一、《环球邮报》的老板乔治·布朗(George Brown)就是其中之一。

被绞死的美国黑人造反首领,堪萨斯州的约翰·布朗(他本人是白人),当年也曾把Chatham作为大本营。

一条underground railroad,其中故事多多。要是哪位对加拿大历史有兴趣,不妨读读。

加拿大历史不长,却也波澜壮阔,值得一读。

几句题外话。常听人讲中国文化如何不好讲国人因为受了不好的文化熏陶而如何不好,还有西方文化如何优越接触了以后才知道昨非今是。老七倒是觉得,这话还是留着,等自己把中国和西方过去的故事稍稍弄清楚点,再说不迟。

其实人这东西,本质是极相近的。

文明这个东西很复杂微妙, 人们一般是受所在地的主流意识左右,不太容易保持

作者: 江毅 注册 | 06/30/2006, 11:13:03 | 作者档案 | 修改 | 回复 | 线索的首篇 枫华茶园首页

独立思维。比如这边媒体骂中国的多一点,有些人就以为中国就真是一片黑暗。

其实正如楼上所述奴隶史事实所反映,世上事物从来就不是单一性的。

比如,被人们顶礼膜拜的人权自由至上的西方民主制度历史上曾长期和种族主义、殖民主义、贩卖黑奴和谐并存。中国政府把中国从历史上的深谷点硬是生生拖回升势强势、举世瞩目地解决了十几亿人的生存权和发展权、经济发展速度引领世界,但其历史上及现时也存在很多错误和局限性。

顺便提一下,关于中西文明:

我注意到西方社会更多(片面地)强调单个人,反之,中土传统文明有较多地方强调个人对家庭、社会的责任。

西方的人权理论未做个人人权和集体人权的明确区分表述,又在相当程度上忽略了集体人权的全面性。

另外,就人群生活状态而言,西方文明中离散性大,中土则人之间联系紧密得多。

修改人: 江毅 于星期五, 6月 30, 2006, 11:21:39

所谓现代文明,原本是由一些不很文明的人、用一些很不文明的方式传播的

作者: 老七 注册 | 06/30/2006, 12:32:52 | 作者档案 | 修改 | 回复 | 线索的首篇 枫华茶园首页

古代也差不多。大汉的征服,也曾是极具掠夺性的。大兵所到之处,如不称臣进贡,就当斩尽杀绝。

原在北美的印地安文化,通常被称为是原始文明。其实这也是一种文化歧视。美国民主的祖宗,还是莫哈克部落的印地安人呢!

当然,国际通行的标准是,有钱的文化便是先进的,不管他的味道是血腥、是铜臭、还是罂粟花香。

作为一个现代人,你必须接受这个标准。在这一点上,个体的自由是很有限的。

说起土著文化,民族文化,文化歧视文化侵略,还有加拿大的多元文化,又是个大话题。

修改人: 老七 于星期五, 6月 30, 2006, 12:36:07

幼河兄好

作者: 老七 注册 | 06/28/2006, 21:40:27 | 作者档案 | 修改 | 回复 | 线索的首篇 枫华茶园首页

不是休假,回来了。

见闻倒是没什么好写的,待有空闲,该把加拿大的故事接着写下去--就是司令说的那什么“史学幻觉症”。可惜,总静不下来。另外,真要动笔的时候,才知道原来那些道听途说太粗,还有很多细节得去搞清楚。

上次开了头的那个,一七五九年,英国军队在魁北克打败法-加联军的故事,真的挺值得讲的。其实在中国也是,每次的改朝换代,都是惊天动地,比如秦末的项羽,让人唱了多少代。

再有,什么是加拿大的历史?一八六七年前,怕只有魁北克城这一段,是英、法、土著们都拿它当个历史大事的,虽说各自的感觉不一样。

其实加拿大再往后的事情,也常常是如此的不明不白众说纷纭。比如咱们挺当回事的铁路华工,洋人们就不那么在乎。还有Riel造反的事,一次大战的参战,六十年代魁北克的宁静革命,等等等等,不同族裔的看法可能完全不同,不同利益集团的解释也可能是南辕北辙。再比如,白求恩,好像也就是这些年中国人把他的名声抬起来了。

也许这就是加拿大特色吧?借其独特的历史来理解美、加之间的区别,好像更容易些。

还是那句话,别管是甚么颜色,人的本性,无论作为个体还是作为群体,其实相差不多。都会追求所谓的义,也都顾及所谓的利。套咱们孔圣人的标准,都“君子”过,也都“小人”过(子曰:君子喻于义,小人喻于利)。

不妨把历史当个故事来听听,还得多听几个版本。听过之后,也许能对别人更宽容些,也对自己更宽容些--我觉得这才是要紧的,起码闹个活得自在。所谓愤青也好,汉奸也好,其实都挺正义,就是有点太对不起自己了

扯远啦!赶哪天都有空,从头聊。

http://www2.fhy.net/cgi-bin/anyboard.cgi/BBS/?cmd=get&cG=43331343&zu=34333134&v=2&gV=0&p=