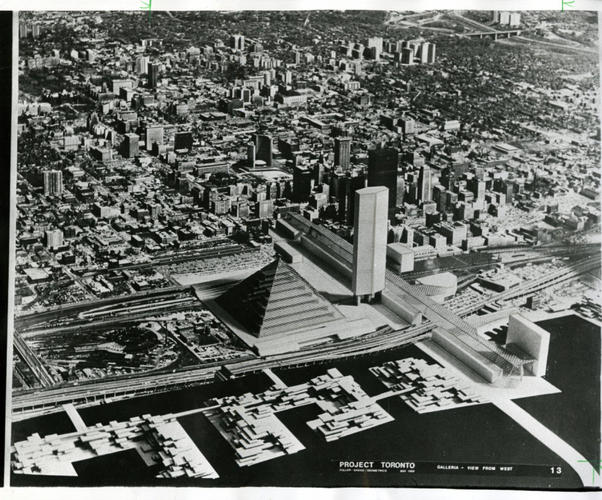

A 1968 proposal by renowned American innovator Buckminster Fuller and called Project Toronto suggested building a giant pyramid on Toronto’s waterfront. CITY OF TORONTO

From great glass pyramids to gigantic Ferris wheels; a history of Toronto waterfront development

Robyn Doolittle

Urban Affairs Reporter

The vision is so jaw-droppingly exciting that it would surely earn Toronto’s waterfront international attention.

Imagine this: nestled against the water’s edge near the foot of University Ave, a great crystal Pyramid towering 20 stories high and housing shops and commercial space. You’d arrive at the pyramid via monorail, which linked together an impressive array of boutiques, restaurants, art galleries and cafes, extending from the downtown core.

Project Toronto, as it was called, was proposed in 1968 by renowned American innovator Buckminster Fuller.

So while eyebrows may have raised when Councillor Doug Ford mused about building the world’s largest Ferris wheel, among other things, along Lake Ontario, the pyramid plan reveals this city has a long tradition of fantastical waterfront schemes.

Or more accurately, Toronto has a history of spending years developing one plan, only to have it ripped up in favour of something even more grand.

This, explains Gabriel Eidelman, a University of Toronto PhD student who is considered the leading authority on the history of waterfront politics, is why Toronto’s shoreline stands in its current uninspiring state.

“Time after time we have periods of long-range planning with multiple stakeholders and then there’s a change of leadership and all that planning gets thrown in the lake,” said Eidelman.

And it seems to be playing out again. Next week the mayor’s executive committee will vote on a recommendation to seize back control of Toronto’s Port Lands from Waterfront Toronto, which has spent $19 million dollars and years developing an innovative mixed-use community for a section of the Port Lands — which is southeast of the Don Valley Parkway — known as the Lower Don Lands.

If that happens, it stands to reason the proposed community will likely be scrapped in favour of something like Doug Ford’s vision.

“It seems that every time things are getting close this happens. There’s no collective memory. These projects from the past are never discussed or understood as to why they might have failed,” said Eidelman. “I would say to Ford and anyone else who believes that they have a great vision to look back in the past.”

That past extends to the early 1960s, when Toronto was coming to grips with the fact it was not going to be a great port city. In 1968, the federal government set up the Toronto Harbour Commission to manage those port lands. That commission came up with the Bold Concept plan, which included a large residential community along the water’s edge, near the current Harbour Front area. To find more space, they recommended filling in the lake to the islands. (Most of Toronto’s current waterfront was created by this kind of infilling.)

But then the province started working on the proposal and government lawyers realized the lake bed actually belonged to the Ontario government.

“And the province had its own ideas for how that land would be used,” said Eidelman.

So the commission’s ideas were thrown out and the province came up with its own plan: Harbour City.

The vision was a mix between Amsterdam and Venice, with lagoons and canals and walkways and low-rise housing for about 50,000 people.

Jane Jacobs called it “the most important advance in planning for cities that has been made this century.”

Then in 1971, Bill Davis assumed leadership of the provincial Tories and he killed the idea — even though it was the same party. Eidelman has asked him why.

“He mentioned the cost involved. It also wasn’t his baby. It wasn’t his project. He didn’t feel personally invested. He wanted to show that he was moving in a different direction.”

Enter Pierre Trudeau in 1972, who promised Toronto a waterfront park during an election campaign. This poorly thought out vow sparked nearly two decades of fighting between the federal government and city hall. No one could agree on what would be built and each time the parties got close the players changed, said Eidelman.

Finally, in 1988, former Toronto mayor David Crombie was brought in to sort out the waterfront debacle in a royal commission. His work, which took four years and $9 million, produced a number of recommendations.

A trust was established to review those findings, once again starting from scratch. Enthusiasm waned.

It took a possible Olympic bid in 1998 to get the parties fired up again. All three levels of government came together to develop a plan. The Port Lands would host the athletes village.

The bid lost, but that initial work was passed on to an organization, which would eventually become Waterfront Toronto in 2001.

Then Toronto experienced a change in government in December 2010.

http://www.thestar.com/news/article/1047537