作者:金钟

更新于∶2011-11-03

● 开放杂志编者按;新近出版的《司徒华回忆录》,提到八九年六四事件后港支联曾协助一名“毛泽东情妇”移民美国。她就是毛身边仅次于张玉凤、孟锦云的女人陈惠敏(陈露文)。本刊主编一九九七年在香港与其相识,协助她出版回忆录,并记录多次深入谈话的内容,撰成此文,以飨读者。

这是一段奇遇,故事发生在香港回归的一九九七年,迄今已经相隔十四年。

我在香港做新闻人物专访,可谓“不计其数”,一般都是当月发表,为甚么对这样有趣的人物故事,竟能搁置十余年隐忍不发?那要从和陈小姐的最后一次见面说起。

一九九七年五月二十三日,是我太太的生日,三天前约陈小姐一聚,她说要请我们吃饭。晚上七点,我们在铜锣湾雪园酒家相会。陈小姐是一位很健谈的人,我们已经见面谈过几次。谈她要出书的事。她委托我做经理人(口头表示),帮她找出版社,让出版社出钱买她的故事,她深信“李志绥写的都是关着门外的事,关着门里面的事,要我来写”,一定比李志绥的书更畅销。她说台湾两大报都要连载她的故事,还有一位女作家蒋×也要为她写书,她拒绝了。她问我李志绥回忆录赚了多少钱?我听说四十万美金。她不屑地说:“四十万?炒一层楼就够了,我不是垃圾,我是贵妃。”

雪园饭店:不愉快的分手

她跟我谈过不少跟毛一起的事。我也确实看好她可能出版的这样一本“红朝秘史”。我曾认真地追踪李志绥的故事,在李医生生前做过对他的独家专访,发表过李医生回忆录续集的片断。他去世后,专门出版纪念文集《反叛的御医》。李医生是第一位站出来指证毛荒淫无道的人,他的权威见证,引起广泛关注与好奇,他的回忆录一九九四年出版后,畅销至今。但是,还没有第二个人出来现身说法印证李志绥的书,现在有了这位当事人,和毛有过多年亲密关系的前空军政治部文工团女演员,要和盘托出,我当然义不容辞,竭力成人之美。

她问我,找出版社的事进展如何?我坦告:“不顺利,人家嫌你要价太高,中国时报总经理黄肇松先生告诉我,鲍威尔(美国三军联席会议主席)的回忆录才值五百万美元”!鲍书中文版权才二万美元,但陈小姐一直不愿接受降价的条件,我反覆解释,西方出版社打造一本畅销书要下很多功夫……当她知道出书的困难后,就开始抱怨我不懂得“报喜不报忧”,抱怨我没有安排她亲自跟出版商谈,她说她的精采故事一定能使对方高价出手。

说着,她突然问我:“我跟你说了这么多,你为甚么不写?徐四民带个摄影师找我,我没有同意,就写了一篇,说我是毛的‘红颜知己’。”徐是《镜报》月刊前社长。

我一再解释,我没有写,因为是谈出书而不是报导。她说,写访问和写书,有什么不同!我说,要写,也要在七一之后,马上就是“七一回归”了,我们要准备大型专刊。她仍然听不进去。直到晚餐结束,我们走在街上还在大声和我争吵——没想到会是这样不愉快的结局,她说以后见面难了,她不会再来香港。九七之前她一定要离开香港,她计划去澳洲,做投资移民。

我太太非常失落,一个生日晚会,竟然要忍受老公和一个女人不停地争吵。直到和陈小姐分手,她才大叹一口气,一路无语——嫁给这样的老公多么无趣!没完没了的政治!政治!

我也异常沮丧。九七前的生日——我记住了这一天。那是我和“毛的女人”交往的终结。留下的是一个专事记录她谈话的小本子,和为她拍的一些照片。接着是香港百年历史的大日子,九七回归大典,全球数千记者涌来香港。采访和被采访,夜以继日,陈小姐的故事,当然排不上日程,而且,那最后不愉快的记忆也让我不自觉地压抑了平日采访中的写作冲动。最近司徒华回忆录提到“毛泽东的情妇”,提醒我不能再拖延这笔文债。

揭开和孟锦云当“现行反革命”之谜

第一次会见陈露文小姐是在一九九七年春节期间的二月十二日,在九龙祝家庄饭店,那是透过张宁(林彪的未婚儿媳)的介绍,因为九六年八月同事蔡咏梅采访过张宁,而张宁和陈露文同是前空政文工团的舞蹈演员,她们都是来自南京的军人家庭。张宁和陈露文还有联系,知道陈在香港。于是,我和蔡一道去见她。

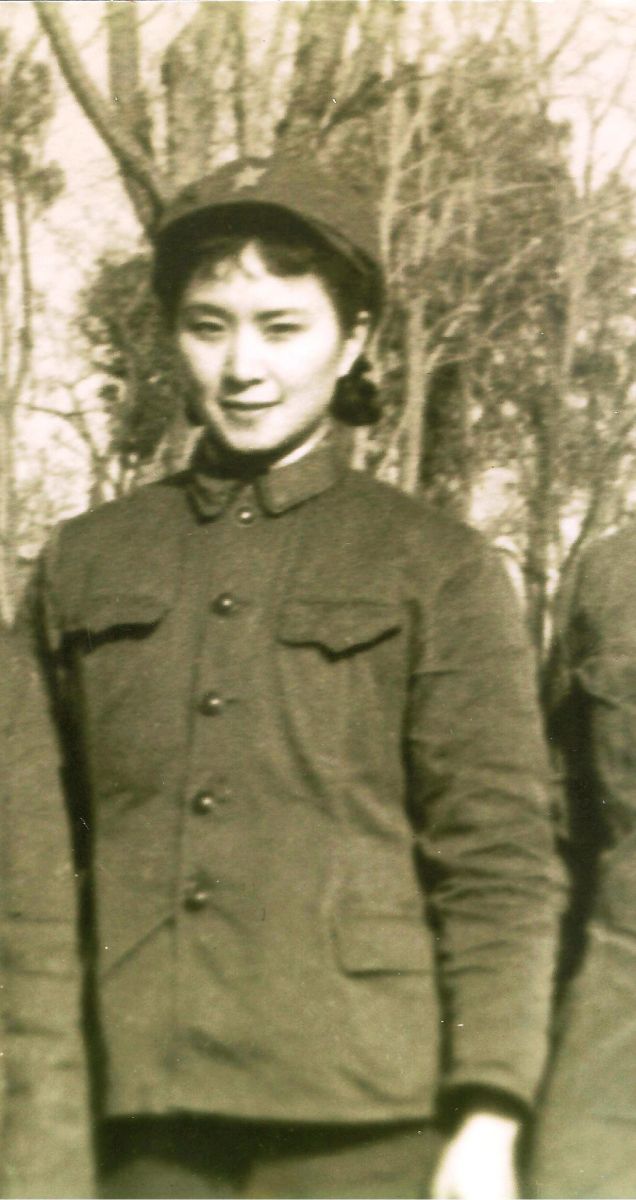

我的好奇心可想而知:为毛所宠的宫女,是天生丽质,还是美人迟暮?我们见到的是一位中年妇女,笑脸相迎,剪着短发,挽着一个啡色手袋。精神旺盛,一眼可见是属于性格开朗热情的一类女性。个子大约有一米七,根据她后来的描述,她应是四十九岁。当然,此时很难想像她在毛身边的容貌,毕竟,她离开毛已经二十一年。

打开话匣子,她可真是有点“口没遮拦”,非常爽快地说往事。我们没有一句废话地便切入毛的话题上,问她是怎样走近毛的身边?她说,第一次见毛主席时,只有十四岁,那是一九六二年。她在空政文工团舞蹈队“上班”,直到一九六七年文革初期。她们那时每周两次去中南海陪毛跳舞。

“为甚么一九六七年就停止了?”

“那时文化大革命造反有理”,陈露文说:“我们也不懂政治,跟着发牢骚,我和孟锦云一起议论毛主席,说毛像皇帝,三宫六苑,我们算甚么?是妃子要册封,是妓女要收钱,是舞女要好玩,我们什么都没有——这话被文工团的头头刘素媛听到,刘连夜去向毛报告,毛听后只说了两个字:造谣!就把孟锦云和我抓起来,打成现行反革命,遭到毒打,我被送去东北。说我们反对毛主席。”

我们知道,毛晚年身边有两个宠女:张玉凤和孟锦云。张之受宠,介入政治之深,已不是秘密,孟在毛死后较低调,只有一本郭金荣着《毛泽东的黄金岁月》(一九九○年出版,二○○九年又重炒一本《走进毛泽东的黄昏岁月》),是孟的口述之作,虽是党性作品,却也透露了一些细节。最引人生疑的是,孟这样一个陪毛跳舞的女孩,怎么突然成为反毛的“现行反革命”?郭的书中称,孟案是当年的“一号问题”,谁也不准打听,不准传说,是涉及毛的绝密。而七五年夏天,毛又突然将孟收回身边工作,此时已婚的孟,想要一个孩子,毛竟不予批准。孟戴着反革命帽子,在毛身边,甚至可代毛圈阅机密文件……这在那全国斗得你死我活的时代,是何等荒谬的事!

●文革中,中南海一组,毛身边的工作人员:前排右三陈惠敏,右二张玉凤。

自由进出香港许家屯办公室

因此,海外许多评论都认定孟和毛的关系不仅陪舞还有陪睡。现在,陈露文的披露可视为一个旁证。她和孟锦云同年,事后遭遇更惨。林彪事件后,她得以从东北送回北京,挨打的伤痛,遗留至今。后来再进中南海,直到毛死前。前后经历十四年。

陈露文说,她的本名是“陈惠敏”,为了隐蔽其身份,才改名陈露文。张戎在《毛泽东鲜为人知的故事》的采访名单之“身边工作人员、女朋友”中,陈惠敏和张玉凤、孟锦云在列。

陈露文说,她是毛身边女伴中,唯一的干部子女。张玉凤是东北籍的列车服务员、孟锦云是出身不好的湖北平民之家。而陈露文之父陈玉生是新四军第三军分区的司令员,前香港新华社社长许家屯曾在陈玉生部抗日地区任泰兴县委书记,后任陈部政治部副主任。许在九七年九月香港《苹果日报》专栏中提到陈玉生抗日初期是中共秘密党员。

因此,凭借其父曾是许家屯的上级,陈露文八三年来香港后,便可自由出入新华社,有时直入许家屯办公室。陈说,许家屯常告诫她不要“乱说话”,尤其是关于毛的话题,甚至吓唬她,要小心,否则会被暗杀,被绑架回去。(许还说他亲自批示过江苏歌舞团一名因说出和毛有一夜情的演员判处死刑)。后来怕影响不好,许家屯便下令新华社门警不让陈露文随便进入。

一九八六年八月,陈露文果然出事。那年她回北京被国安在西苑饭店绑架。藉口是她在外面讲毛的私事,泄露党的机密。关在香山双清别墅,被严密看守,住在一个二层楼上,关了一年八个月,才放她回南京老家。

后来,中央派向守志(南京军区司令员)和江苏省委书记等人向她父亲宣布陈露文没有问题,“父亲对我的事管不了,只盼我走远点”。她父亲一九九四年去世,九十六岁。去世前住南京,任江苏省政协副主席。陈父受到尊重,是因为早年自组游击队抗日,为国民党收编后,接应新四军建立苏北根据地,立下大功,任新四军(三野)第三纵队司令,副司令为叶飞、张爱萍。陈露文仅有的小学教育就在南京军区子弟小学(卫岗小学)入读,和张宁、刘伯承之女、许世友之女同窗。

●前香港新华社社长许家屯(左二),曾是陈惠敏(左一)父亲新四军部队的下属。摄于文革期间。

英国特工认证她是毛的情妇

八九学潮失败后,陈露文看到很多人逃亡香港,她便趁机偷渡,重返香港。走的什么路线?她没有说。最近司徒华回忆录《大江东去》出版,其中提到“黄雀行动”也帮了一名“毛泽东情妇”去美国。当即令我想到陈露文。

华叔提到此妇人的特征:①带有一名八岁儿子;②曾是解放军文工团;③毛死后嫁给南京军区副司令之子;④从事军火生意;⑤曾关押北京西山;⑥花了二十万元偷渡来港。

对照陈露文向我谈到的情况,此妇是她无疑。她确有一子相伴,我也见过,九七年十九岁,个头高瘦。八九年应该是十岁。陈露文的婚姻也没错,是南京军区副司令之子,名叫“段焕京”(这是陈所述,查当时南军副司令名段焕竞,怎么与子同音?)她说,毛死前四个月曾嘱咐她,赶快离开北京,到南方去,嫁人。她将此事告江华、叶飞,他们认为是毛安排后事。她遂下嫁段家,一年后诞下男婴。丈夫湖南茶陵人。对这段婚姻,她描述道:

“结婚几天,我就感到厌倦,我们在一起,一点情趣也没有,乏味之至。他甚至不能谅解我和毛的关系,我们的孩子被他骂做毛的杂种,竟拿来摔,只有离婚。”

为查证华叔回忆录的记载,我特地询问支联会常委、立法会议员张文光先生。原来“毛情妇”这单案子是他经手办理的。张文光说:八九年的一天,有人带了这位妇女和他儿子来见我,说了她和毛的关系,要我们帮她移民美国。我立即报告港府政治部保安科,希望安排和这女人接触,查明真相。港府一名老外,相信是英国高级特工,随即和该母子见了面,很快通知我,说没错,是毛泽东情妇。

张文光说,他将此事报告华叔,我们都很惊讶英国特工收集中国情报的能力。但是有些细节,华叔老了,记得不准确。例如是否去了美国?

这点,华叔书中是有差错。因为陈露文八九年来港,一直到九七前才办成移民,她告诉我已办好去澳洲。几年后,又有人告诉我,她其实是去了英国。九七后我和她就断了联系。

毛认陈露文是女儿和情人

春节期间见过陈露文之后,二月十九日,邓小平死了,这是大事。两天后,陈约我去她家看照片。二十二日下午七点,我赶到她在西贡西沙小筑9E的家中拜访并看照片。这是我最关注的事——现在,史料对于出版者而言,最重视的莫过于“老照片”,李志绥医生如果没有那些和毛的合影,其公信力一定会大打折扣。香港八卦报纸的“狗仔队”,目标也是为了猎取现场照片以取信于市民。

但陈露文坦白告诉我,她没有和毛的照片。为什么?她说,这方面毛很谨慎。尽管外传毛的女人无数,但公开的照片只有两个:张玉凤和孟锦云。因她们二人是有正式身份的:毛的机要秘书和护士。可以出镜。而她“什么也不是”。我问她:毛认为你是什么?

“毛说过,我是他的女儿和情人。我反问他,那不是乱伦吗?毛听后大笑不语。他的伦理就是与众不同。他也说过我是‘尤物’,初初我还不明白尤物是什么?后来才知道,就是今天香港很爱说的性感。”

我跟她解释,大陆过去没有“性感”一词,就像“做爱”二字也是文革后才流行一样。尤物,字面上是你特别喜爱的物品,用之女性,便有风骚、妖艳之类的意思。俗语难听点:叫“骚货”。她听了笑起来,说,我比张玉凤、孟锦云大概要骚一点。(干部子弟总是比较放肆吧。)

她说没有和毛的照片,其他的都有。于是,她拿出一大盒照片,倾倒在沙发上,让我看。大部份是黑白的老照片,而且尺寸小。我顺便挑了几张,她同意我去复制。如图这张在中南海和张玉凤等的合影,她在前排中间。似乎没有孟锦云。还有和一些老干部的合影。

毛是政治家,邓小平只是政客

趁邓小平尸骨未寒,我挑起话头,问她毛邓的恩怨,可有所闻?陈露文说了不少。

她又是从自己说起。她说,八六年她在北京被国安关押,事关邓小平要整杨得志。邓小平之女毛毛的丈夫贺平(总参装备部副部长)被指垄断军火生意,又不报告总参谋长杨得志,直接向邓汇报。杨为此而不满,曾在军委会议上,当着邓的面,指责贺平做法反应不好,让邓很难堪。邓便找岔报复杨:抓她,逼她交待“出卖情报”。她说,因为杨得志是她爸陈玉生的部下,她也和杨相熟,邓要借她打杨。

其间是否有生意上的冲突?她在二月十六日对我说过杨得志追求她,给她军火生意做。华叔回忆录也提到过她和前夫“做军火生意”。她说过,毛死后,粟裕(大将,陈父上级),杨得志都爱她,表示可以离婚,和她结婚。

陈露文对父执辈的将领中,对杨得志上将(1911-1994)最为好感,说他为人正直,是一名杰出的战将。她告诉我,一九七九年,邓发动的惩越之战,许世友指挥东线,大败;杨得志指挥的西线却获得大胜,因而,八○年晋升为总参谋长。粟裕曾对陈露文称赞其父早年救援新四军,说“没有你父亲,我们待不下去”。粟裕曾任新四军一师兼六师师长。(毛曾盛赞粟裕的战功,说粟裕应领元帅衔,但粟裕谦让,三次辞帅,故位列大将第一名)。陈露文没有接受两位将军的追求,尊敬他们为父叔长辈。对我说,他们都是“你们湖南人”。

陈露文口中的邓小平根本不值得尊敬。她拿邓与毛比,说毛从未动用军队攻打学生;不会当众训斥耿飚黄华“胡说八道”;邓在军内排斥三野,重用亲信,刘伯承元帅性格内向,功名就被邓抢了去。她说,重用太子党,其实是邓的主意,邓说还是自己的子弟好,邹家华、李鹏、江泽民才上得去。她说毛是政治家,邓只是个办事能力还不错的政客。邓恨死了毛,要拉毛下神台,故意放李志绥出来,搞臭毛……

对英国记者介绍中南海舞会

我问她,毛还有什么东西赠送给她?

她说,毛有诗和手稿赠她,她都已转送给人,包括宋任穷、江华、陈昊苏、陈小鲁、陈丕显、陶斯亮、杨得志、粟裕等,共有十多首诗。我问她写了甚么?她说只记得一句:“来年相会在梦中”。

她说,高干中不少人都知道她和毛的关系,有的见了她还下跪叩头,叫她“娘娘”,求她在毛面前说情,让他们“落实政策”。她和陶斯亮是好朋友,是干姐妹,她多次和毛关说陶父亲(陶铸)的事,但不管用。她说理由(陶斯亮丈夫,报告文学作家)还打算写她的故事。

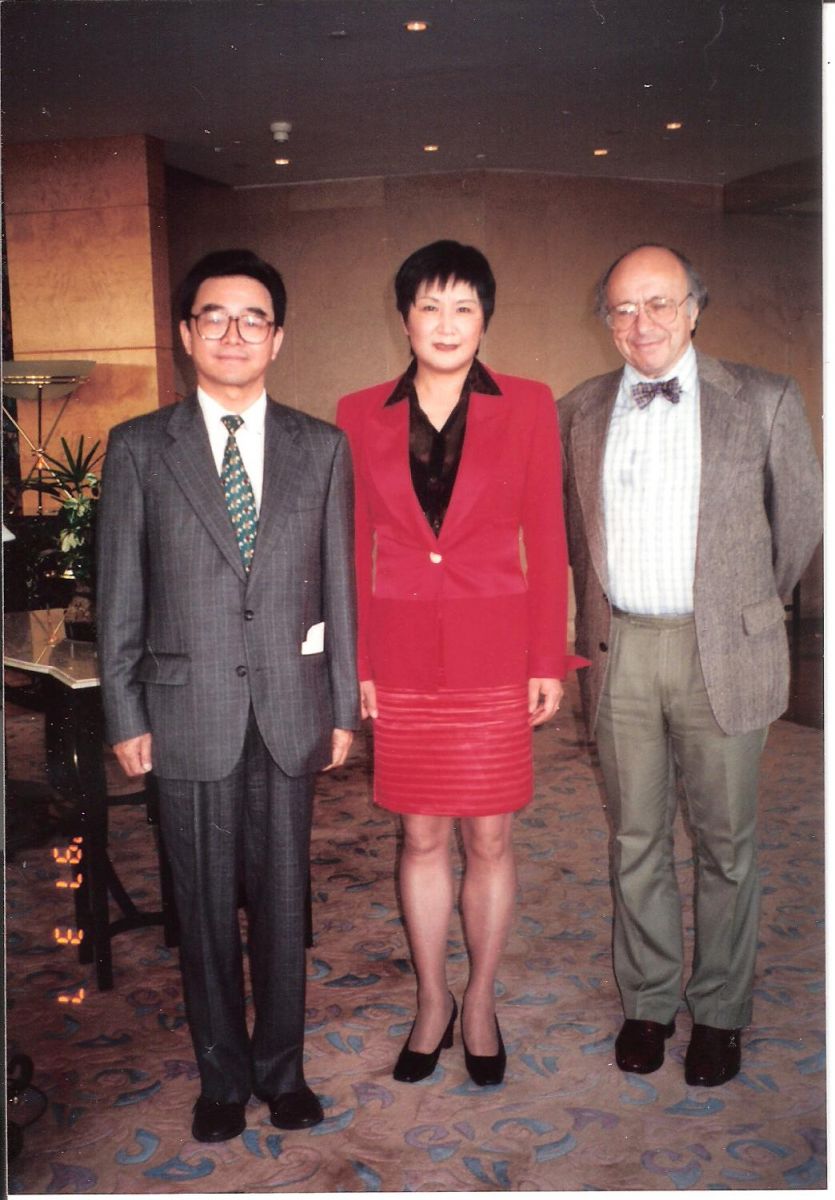

●1997年3月摄于香港万豪酒店。左起:金钟、陈惠敏、梅兆赞。

陈露文和毛泽东的性关系,究竟是玩伴还是宠妃?是我一直是想探清的问题。每次见面她都会谈到一些。例如三月七日,我特地安排英国资深记者梅兆赞(Jonathan Mirsky)博士和陈露文见面。在万豪酒店自助餐谈了两个多小时。那天她着一袭红色套装,短裙合身,神采奕奕。梅博士懂中文,不用翻译,对中国问题素有研究。我请陈小姐说话慢一点就行。

她说了八六年在北京被关押三年的经过后,便说明中南海伴舞的情况。她说那是一九六二年开始的一项“政治任务”:中央首长要借跳舞有益健康。那时是困难时期,她十四岁,已发育得有一米六八的个头。去中南海跳舞,对她们这班女孩有一个实际的好处,就是可以吃一顿丰富的晚餐,富强面和美味的炒菜,外面是吃不到的。她们的舞场,由空政、公安文工团负责,专为毛泽东、刘少奇、朱德三首长服务。舞场百余人,乐队伴奏,女孩子一排坐在一侧等候邀请上场。

她说是有休息室,有女演员陪毛,端茶入室,一个多小时不出来,有没有人上床?她不知道。舞会每周两次,每次要跳到三、四点钟,白天还要上班排节目,宣传演出,“非常累”。周恩来的舞场要低一级,由海政文工团伴舞。

高层个个玩女人,周邓都不例外

当问到《叫父亲太沉重》,周恩来有没有婚外情时,陈露文毫不犹豫地说:周有情人,是一位将军的妻子,比她大十岁,是海政的舞蹈演员。周常打电话找她,在她们那圈子里人皆知道。她说“艾蓓完全是周恩来的女儿!”艾的养父是个副部长,生母在北京,当然不会公开。

陈露文解释说,高层除陈云身体衰弱,林彪“抽白面(鸦片)”外,个个都玩女人,老帅朱、叶、老邓都不例外。他们当这是最高的特权享受。有的高干还“扒灰”,搞儿媳妇,告到毛那里。下级为了巴结上级,也以介绍女孩子为最好的手段。有人专机从杭州送一女给毛,毛看不上眼,当即飞返杭。毛曾要她介绍姐姐来京(陈露文一家十姊妹,她排行老七),被她拒绝。张玉凤就没有拒绝介绍其妹到中南海服侍毛。

陈露文谈到毛的生育能力时,说一段颇为大胆的话:“毛有生育能力,李医生有帮毛的女人打胎。只是到老了,才不行,后来已经不能射精,只是精神上发泄,玩一玩。”

当时,我特别注意到梅博士对“不能射精”一语的反应,可能是陈说得太快,梅博士没有听到,我却听得很清楚。陈还说,文革开始后,江青大出风头,她完全不理会毛的性事,只盼他多玩些,她好在政治上尽情发挥和抓权。

梅兆赞后来问我:关于陈露文的事,香港记者为什么没有人去追踪?我回答说,可能是怕太敏感吧,连李志绥的书出版,香港媒体兴趣都不大,感兴趣的是大陆人。针对陈露文想移民美国的要求,梅博士还帮她找美英驻港领事探听过,他说,领事馆的人早已认识她,说,和毛上过两次床,就想办政治庇护?

那天在万豪,陈露文胃口很好,吃了不少生蚝。

和毛是如鱼得水的忘年之交

谈毛的私生活,正月初十那天,在铜锣湾航空大厦的谈话较为详备。下午三点四十,我迟到十分钟,陈露文已在拐弯街口等我,身着一套白色裙装,配白色高跟鞋。她带我上六楼,介绍这是她以每尺九千元炒得的一层楼,正待价而沽,我们在一张写字台,相对而坐。她一开口就讲了半小时。说做军火生意、炒楼曾赚到两个亿,现在还有三千万港币在手。

我问她:来香港多年为何不结婚?

她说:“我在大陆有很多人追,文革后有两个中央委员追我,简直疯狂。来香港也有什么董事长追我,还有人给我介绍大富豪×××。我无动于衷。我为什么要离婚?就是因为和毛主席的那段关系太刻骨铭心,其他人就显得平淡无味。”我一边记录,一边请她解释。

“随着权力的增长,他的性欲也变得旺盛,以至变态,无人可以适应。因为毛是一个非常态的人,性自然如此。毛是做爱的高手,不是一般的性交。他很反感周恩来装圣人,情人多,不敢做。也反感刘少奇说他老婆都是正式结婚,只有我一个乱来?毛的可爱就在于他的真,他敢说,他就是秦始皇。”

“有张玉凤、孟锦云在身边,还不能满足他吗?”我问道。

她说:她们两个贤淑,听话,但呆板,不会做,只当自己是工具,不主动,没法让毛有如鱼得水的快乐。我不同,毛可以当她们的面叫唤:“陈惠敏勾引我,让我看不了书!”

她没有说怎样勾引毛。但说她常在毛面前赤裸裸地看书,以请教问题靠近毛,毛很欣赏她的眼神……只能想像,六六年才十八岁的她,以舞蹈演员的裸体示人,七十岁的毛怎能招架得住?她说,毛的性意识特强,第一次强暴她时,将她的衣衫撕烂,让她“一下子完全崩溃了”,经过多次强暴,他们终于成了忘年之交!她说毛的肤色光滑红润,可爱极了。

她透露毛有些怪癖,爱光屁股放响屁,还让她们记录一天放多少次。他认为放屁是健康的表现。毛喜欢和她互相逗弄,不是单方面满足。还不止一次让她看他怎样和其她女孩玩。她说毛熟读《金瓶梅》,说“贵在意淫”。他不看色情电影,“有我们在身边陪他,足够了。但江青看三级片。”她说,毛的性致很高。我有时和他说文革的事,他很烦,说:不要理那些屁事,还是办我们的事要紧。

陈露文和毛讨论过恩格斯的婚姻理论,一夫一妻制由私有制而引起,也会随私有制消灭而灭亡,她和毛都赞成“共产共妻”。

●陈惠敏(右)与粟裕大将摄于文革后期。粟裕曾是陈父军中上级。

恋恋不忘毛的帝王之恩

和陈露文的谈话,根据我的记录共有六次,每次都在两三个小时以上,出书始终是她最关心的事。她说,很多人都是想利用她发财。北京也有人找她,要她为党史留下材料,被她拒绝。我相信,她是有心出版一本比李志绥回忆录更为真实的书,记载她和毛的前后十余年的情缘。她一再说明,所以要价数百万美元,是要得到补偿,“蹂躏了我的全部青春”,有一次非常伤感的诉说,“毛把我害得这样惨,弄得我和任何男人都不能满足,结婚的欲望也没有了!”但是,她并不缺钱。她也想出名,甚至说,以后要别人提到毛就知道我,像杨贵妃和唐明皇一样。

她非常自信。声称沾上了毛的灵气。其实,也有毛的不可一世和无知,造就她的野心。大陆给她“封口费”,让她炒楼,一次损失三千六百万,面不改色。她气愤地骂,英国美国当她垃圾,不给她移民,视她比一个流亡学生还不如。她要出一本超过李志绥的书给他们看看。

她不讳言,对毛的至高崇拜,怀念毛。她说时常托梦,毛对她说,“只要不跟别人一道反我就好,对我的事,实事求是就行了,我不怕暴露。”她说,毛是天才,超凡脱俗。毛喜欢她,也是因为她聪明、坦白、反潮流,不仅仅是她漂亮性感。江青也是和毛的性格相互吸引,她是绝对忠于毛的。毛身边的人,如“汪东兴很坏,干了很多你想像不到的坏事”。

她说,她不怕国安追杀,他们找她谈了五次,要她回国去住,给她房子。她不要。但是香港不安全,她一定要走。到外国生活,和儿子相依为命。她预言毛派还会在中国上台。

从一九九七年,她对我寄与希望,出版她的回忆录,匆匆十四年过去,事如春水了无痕。她在哪里?别来无恙?在大时代的洪流中,多少风流人物都已瞬间即逝,她想做的“乱世佳人”之梦,不过是一代暴君的一个注脚而已。

她说的这些故事有多少份量?读者和红墙中人自可判断。“白头宫女在,闲坐说玄宗”,也算一篇故事新编吧。

(二○一一年九月二十日于香港。原载《开放杂志》2011年10月号,照片作者提供)

金钟注:本文发表后,承不少朋友读者表示兴趣,并询问有关情况。谨此致谢,同时对个别细节、错别字作出补正。 ——2011年10月18日NY

毛泽东情人自白录(英文版)

作者: 金 钟

更新于∶2011-11-02

The recently published memoirs of Szeto Wah [The Great River Runs Ever Eastward: Szeto Wah’s Memoirs] mention that following the 1989 June 4th Incident, the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements in China at one point assisted a “former mistress of Mao Zedong” to emigrate to the United States. Within Mao’s harem, Chen Huimin, also known as Chen Luwen, was second only to Zhang Yufeng and Meng Jinyun. I came to know her in Hong Kong in 1997, intending to help her publisher her memoirs. I took notes on our several meetings, and this article is drawn from those notes.

This is the story of an encounter that took place 14 years ago, in 1997, the year Hong Kong returned to Chinese sovereignty.

I have carried out countless interviews with newsmakers in Hong Kong, and typically publish them right away. So why did I hold back on telling the story of this interesting person for more than ten years? In explaining this, I should start with the last time I met Ms. Chen.

May 23, 1997, was my wife’s birthday, and Ms. Chen had arranged to treat us to dinner that evening at a restaurant in Causeway Bay. Ms. Chen was a lively conversationalist, and we had already met several times, mostly to discuss publication of her book. She had verbally appointed me her agent to find a publisher who would pay for the rights to her story, firmly believing that “what Li Zhisui [Mao’s personal physician] wrote about was outside matters, but it is up to me to write what happened behind closed doors,” and that her book would sell even better than Li’s. She said that both of Taiwan’s major newspapers wanted to serialize her story, and that a female author, Chiang X, also wanted to act as her ghostwriter, but that she had refused. She asked me how much Li Zhisui’s book had earned, and I said I’d heard US$400,000. She disdainfully remarked, “Only $400,000? I can make that in one real estate deal! I wasn’t some slut, I was an imperial concubine!”

She told me a great deal about her life with Mao, and I actually believed she had a chance of getting her “secret history of the Red Dynasty” published. I had diligently followed Li Zhishui’s story, and had interviewed Dr. Li, while also publishing portions of his memoirs in my magazine. After he died, I had commemorated him by compiling articles into a book entitled The Rebellious Doctor of Mao. Dr. Li had been the first person to come out publicly with Mao’s licentious and immoral behavior, and his authoritative testimony had attracted widespread concern and interest. His memoir, published in 1994, continues to sell today. However, no second person had come forward to back up Li Zhisui’s account. Now there was this eye-witness, a former female member of the Air Force political department’s song-and-dance ensemble, who had spent several years in an intimate relationship with Mao, and who wanted to reveal everything. I naturally felt duty-bound to help her achieve her goal.

On that evening in May she asked me about my progress in finding a publisher. I frankly admitted, “It’s not going well, because people feel you’re asking for too much money. The China Times general manager, Mr. Huang Zhaosong, told me that only someone like Colin Powell [the former US Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff] was worth paying US$5 million for his memoirs.” The Chinese-language royalties on Powell’s book were only US$20,000, but Ms. Chen was unwilling to lower her price. I repeatedly explained how much work Western publishers put into a book… After hearing of these difficulties, she complained that I didn’t know how to “report only the good news and not the bad,” and that I hadn’t arranged for her to personally meet with publishers. She said her story was so interesting that whoever heard about it would pay whatever she asked.

She then suddenly asked me, “I’ve told you so much, why haven’t you written about it? Xu Simin brought a photographer to see me, and I refused, but he went ahead and wrote an article referring to me as Mao’s ‘intimate friend.'” Xu [known as Tsui Sze-Man in Hong Kong]was the publisher of the left-wing Mirror Monthly at that time.

I explained that I hadn’t written what she’d told me because my understanding was that we were talking about publishing her book, not about reporting on her story. She said, “What’s the difference between writing an interview and writing a book?” I said I could write an article, but it would have to wait until after the July 1 handover, because I was preparing a special issue for that occasion. This was not what she wanted to hear. For the rest of the meal until we left the restaurant, she continued loudly squabbling with me. I hadn’t expected things to end so badly. She said it was unlikely that we would meet again, because she would certainly have left Hong Kong before the handover, and she would not be returning; she was planning an investment immigration to Australia.

My wife was very disappointed to have spent her birthday dinner listening to another woman haranguing her husband. When Ms. Chen finally left us, she sighed wordlessly — how tedious it was to be married to a husband who talked about nothing but politics!

I was also disheartened. That birthday before the handover — I remember it as the day my dealings with “Mao’s woman” ended. All I had left was a notebook full of jottings from our conversations, and some photographs I’d taken with her. After this encounter came that momentous day in Hong Kong’s history marking the handover of sovereignty from Great Britain to China. Thousands of journalists from all over the world converged on Hong Kong. I carried out interviews and was interviewed day and night, and Ms. Chen’s story simply wasn’t on the agenda. In addition, the unhappy memories of our last meeting led me to unconsciously suppress my normal reporting impulse. It was the recent publication of Szeto Wah’s memoirs mentioning “Mao Zedong’s mistress” that recalled this literary omission to mind.

The first time I met Chen Luwen was during the Lunar New Year holiday in February 1997, when we were introduced at a restaurant in Kowloon by Zhang Ning, a woman who was once the fiancéof Lin Biao’s son. My colleague Tsoi Wing-mui had interviewed Zhang Ning in August 1996, and Zhang had been a member, along with Chen, of the song-and-dance troupe, both women coming from military families in Nanjing. Zhang had maintained contact with Chen over the years, and knew she had come to Hong Kong. That was how it happened that Tsoi and I went to see her.

My curiosity can easily be imagined: would one of Mao’s favored women be a beauty still, or would her charms have faded over time? The woman we met was a middle-aged matron who greeted us with a smile. She wore her hair cut short and carried a brown handbag. She was vivacious, and at a glance it was clear that she was an outgoing and passionate woman. She was about 1.7 meters tall, and according to her own subsequent telling, she was 49 years old. Inevitably it was hard to imagine what she had looked like when she was with Mao, 21 years before.

We talked non-stop, and she spoke about her past with no obvious inhibition or discomfort. I wasted no time in cutting to the subject of how she had become Mao’s companion. She said the first time she saw Chairman Mao was in 1962, when she was only 14 years old. She “worked” in the song-and-dance troupe until the early stage of the Cultural Revolution in 1967.

“Why did you stop in 1967?”

“At that time the Cultural Revolution was all about rebellion,” Chen said. “We didn’t know anything about politics and started grumbling. Meng Jinyun and I discussed Chairman Mao and said he was like an emperor with a harem, and what, then, were we? If concubines, we were entitled to status, if whores we were entitled to pay, and if dancing girls we were entitled to fun, but in fact we had none of those things. Our conversation got back to the head of the song-and-dance troupe, Liu Suyuan, and Liu reported it that same night to Mao. When Mao heard of it, he said two words: rumor-mongering! He had Meng Jinyun and me arrested and labeled counter-revolutionaries. We were thrashed, and I was sent to the northeast. They accused us of opposing Chairman Mao.”

It is well known that Mao had two favored female companions in his later years: Zhang Yufeng and Meng Jinyun. Zhang’s status and deep involvement in politics were no secret. Meng retained a low profile following Mao’s death; there was only Guo Jinrong’s Mao Zedong’s Golden Years (published in 1990, and rehashed in 2009 in Entering Mao Zedong’s Twilight Years), which was an oral account by Meng, and even though a Party product, it still revealed some details. What made people suspicious was how a girl like Meng who had danced with Mao could suddenly become an “active counter-revolutionary” opposing Mao. According to Guo’s book, Meng’s case was the “top issue” of that year; no one was allowed to ask or talk about it, because it involved Mao’s top secret affairs. In summer 1975, Mao suddenly took Meng back to work with him. By then Meng was married and wanted to start a family, but Mao wouldn’t allow it. Although labeled a counter-revolutionary, Meng remained at Mao’s side and was even allowed to sign off on secret documents on Mao’s behalf… It was a truly absurd situation at a time when the whole country was embroiled in struggles to the death.

For that reason, many overseas commentaries held that Meng’s relationship with Mao was not merely one of a dancing partner, but that she had also slept with him. Now Chen Luwen’s disclosures provided collateral evidence of this. She was the same age as Meng Jinyun, but had met a harsher fate. After the Lin Biao incident, she was able to return to Beijing from the northeast, but the pain of her beatings never left her. She subsequently returned to Zhongnanhai until just before Mao’s death, spending a total of 14 years with him.

Chen Luwen said her original name was Chen Huimin, but she had changed her name to hide her identity. The name Chen Huimin is included with those of Zhang Yufeng and Meng Jinyun in the list of people interviewed for Jung Chang and Jon Halliday’s Mao: The Unknown Story.

Chen said she was the only one of Mao’s female companions who came from a cadre family. Zhang Yufeng had been a rail service worker from the northeast, and Meng Jinyun was from an ordinary Hubei family with undesirable class origins. Chen Luwen’s father, on the other hand, was Chen Yusheng, commander of the third division of the New Fourth Army. The former head of the Hong Kong branch of the Xinhua New Agency, Xu Jiatun, had at one time served as Party secretary of Taixing County in the anti-Japanese resistance area under Chen Yusheng, and had later served as vice-director of the political department of Chen’s division. In a column in Hong Kong’s Apple Daily in September 1997, Xu mentioned that Chen Yusheng was a secret member of the Communist Party during the early years of the anti-Japanese resistance.

Because her father had once been Xu Jiatun’s superior, after Chen Luwen arrived in Hong Kong in 1983, she was able to circulate freely within the Xinhua News Agency, and sometimes walked right into Xu Jiatun’s office. Chen said Xu was always warning her not to “shoot off her mouth,” especially on the subject of Mao, and even threatened that if she wasn’t careful, she might be assassinated or kidnapped and taken back to China. (Xu also said he had personally signed off on the execution of a member of the Jiangsu song-and-dance troupe who had talked about a one-night stand with Mao). Eventually, worrying about the consequences, Xu ordered the Xinhua security guards to prevent Chen Luwen from entering without permission.

Something did finally happen to Chen Luwen during a visit to Beijing in August 1986. State security police abducted her at the Xiyuan Hotel on the pretext that she had talked about Mao’s personal matters outside of the mainland, and therefore had leaked Party secrets. She was kept under close watch in Shuangqing Villa in the Fragrant Hills for a year and eight months before being allowed to return to her family home in Nanjing.

Afterwards, the central government sent Xiang Shouzhi (commander of the Nanjing military district) along with the Party secretary of Jiangsu Province and others to announce to her father that Chen had been cleared. “My father couldn’t handle me and only hoped that I would go far away.” Her father died in 1994 at the age of 96. Before his death he lived in Nanjing and served as vice-chairman of the Jiangsu Provincial People’s Consultative Conference. Chen Yusheng was respected because in his early years he had assembled his own guerrilla troops to fight Japan, and after being absorbed into the Kuomintang army, he had helped the Communist New Fourth Army establish its Northern JiangsuBase Area. He had rendered extraordinary service as commander of the New Fourth Army’s third column, with Ye Fei and Zhang Aiping as his deputy commanders. Chen Luwen had studied only through elementary school at the Nanjing Military Region Army Dependants’ Elementary School (Weigang Elementary School), where she was classmates with Zhang Ning and with the daughters of Liu Bocheng and Xu Shiyou.

After the failure of the 1989 student movement, Chen Luwen saw many people fleeing to Hong Kong, and she seized the opportunity to return to Hong Kong illegally. She wouldn’t disclose what route she took. In his memoirs, Szeto Wah mentioned that Operation Yellow Bird had helped “Mao Zedong’s mistress” go to the United States, and I immediately thought of Chen Luwen.

Szeto mentioned several descriptive details regarding this woman: 1) she brought an eight-year-old son with her; 2) she had once been a member of a PLA song-and-dance troupe; 3) after Mao’s death she had married the son of a deputy commander of the Nanjing military region; 4) she was involved in arms dealing; 5) she had at one point been imprisoned in the Western Hills outside of Beijing; 6) she had spent $200,000 to enter Hong Kong illegally.

Comparing this description with what Chen Luwen had told me, I had no doubt that she was this woman. She had brought her son with her, and I had met him in 1997, a tall, thin boy of 19 — that would have made him around ten years old in 1989. Chen Luwen had likewise been married to the son of a deputy commander of the Nanjing military region, a man named Duan Huanjing (this is what Chen told me, and I found that the deputy commander at that time had a name that was pronounced the same, but with a different third character, which seemed rather odd for a father and son). She said that four months before Mao died, he had told her to leave Beijing quickly, to return to the south and get married. She told this to [revolutionary veterans] Jiang Hua and Ye Fei, who felt this was Mao making his final arrangements. She accordingly married into the Duan family and had a son a year later. Her husband was a native of Chaling, Hunan Province. She described this marriage as follows:

“Several days after the wedding, I became fed up with it. We were bored with each other, and our life was empty. He couldn’t forgive my relationship with Mao, and he referred to our son as Mao’s bastard. Things reached such a pass that we could only divorce.”

In order to verify Szeto Wah’s recollection, I made a point of inquiring with Cheung Man-kwong, a Legislative Councilor and member of the Hong Kong Alliance’s standing committee. It turns out that he had personally handled the case of “Mao’s former mistress.” Cheung said, “One day in 1989, someone brought a woman and a boy to see me, saying the woman had been associated with Mao and wanted us to help her immigrate to the United States. I immediately reported this to the Hong Kong government’s Special Branch, hoping to arrange contact with this woman to verify her identity. An expatriate official, I think he must have been a high-level British intelligence agent, immediately met with that woman and her son, and quickly notified me that it was true, she was Mao’s former mistress.”

Cheung Man-kwong said he reported this matter to Szeto Wah, and that they were amazed at the ability of British intelligence to gather information on China. But there were some details that Szeto could not recall accurately in his old age, such as whether Chen had gone to the US. On this point, it appears that Szeto’s account was mistaken, because after arriving in Hong Kong in 1989, Chen stayed there right until 1997, and she told me she had arranged to go to Australia. Several years later someone told me that she had in fact gone to the UK. I lost contact with her after 1997.

Around the time of my meeting with Chen Luwen, Deng Xiaoping died on February 19, and that was a major event. Soon after that, Chen invited me to look at her photos, and I hurried to her Sai Kung home on the evening of February 22. I considered this a matter of great importance, as publishers of historical materials are very keen on old photos. If Li Zhisui hadn’t possessed photos of himself with Mao, he would have had much less credibility. Even the “doggy teams” of Hong Kong tabloids make on-site photos a major goal in order to establish their credibility with readers.

But Chen Luwen admitted that she had no photos of herself with Mao, explaining that Mao was very circumspect in this regard. Even though he was rumored to have had countless women, the only photos ever made public were of him with Zheng Yufeng and Meng Jinyun. Both of them had formal working relationships with Mao as his personal secretary and nurse, so they could be photographed. But Chen was “nothing.” I asked her, “What did Mao consider you?”

“What Mao said was that I was his daughter and lover. I asked him, wasn’t that incest? When Mao heard this, he laughed out loud. He had different moral principles from most people. He also said I was a ‘youwu’ [femme fatale]. At first I didn’t understand what that was. Later I learned that this was what people in Hong Kong call sexy.”

I explained to her that in the past, the term “sexy” wasn’t used in mainland China, just as the term “make love” did not become popular until after the Cultural Revolution. Ostensibly, a “youwu” is something you’re especially fond of, but when applied to a female, it takes on the connotation of a coquette or seductress. A popular but somewhat offensive equivalent is “floozy.” On hearing this, she laughed and said, “I guess I was a bit looser than Zhang Yufeng and Meng Jinyun.” (The children of officials tend to be more licentious.)

Although she had no photos with Mao, she had others in a large box, which she dumped on the sofa for me to look at. Most were old, small, black-and-white photos. I randomly picked out a few, and she allowed me to take them away to make copies. In a photo with Zhang Yufeng and others at Zhongnanhai, she is positioned in the middle of the front row, and Meng Jinyun is not present. There were also some photos of her with elderly cadres.

With Deng Xiaoping’s corpse not yet cold, I took the opportunity to ask her about the love-hate relationship between Mao and Deng and what she’d heard about it. Chen Luwen told me quite a lot.

Once again, she started with herself. She said that in 1986, when she was detained by the state security police, it was related to Deng’s purge of Yang Dezhi. Deng’s daughter Maomao’s [Deng Rong] husband, He Ping (deputy director of the Armaments Department at the PLA General Staff Headquarters), was accused of monopolizing the arms trade, but the report was not made to Chief of Staff Yang Dezhi, but rather directly to Deng. Yang was unhappy about this, and at a meeting of the Military Affairs Commission he criticized the negative effects of He Ping’s behavior before Deng’s face, causing Deng considerable embarrassment. Deng found a way to avenge himself on Yang: he had Chen Luwen arrested and forced her to confess to “selling intelligence.” She said that because Yang was her father’s subordinate, she was familiar with him, and Deng wanted to use her to get back at Yang.

Had there been a conflict of business interests involved? On February 16, Chen told me that Yang had pursued her and had given her some arms deals to handle. Szeto Wah’s memoirs also mentioned that Chen and her ex-husband had been in the “arms trade.” She said that after Mao died, Su Yu (a senior general and a superior to Chen’s father) and Yang were both in love with her and had expressed a willingness to divorce their wives and marry her.

Of all the high-ranking officers in her father’s generation, Chen had the warmest feelings toward Yang Dezhi (1911-1994). She described him as an upright man and an outstanding soldier. She told me that in 1979, when Deng launched the war to punish Vietnam, Xu Shiyou commanded the eastern front and suffered a crushing defeat, while Yang Dezhi commanded the western front and gained a decisive victory, as a result of which he was promoted to Chief of Staff in 1980. Su Yu had once praised Chen’s father for his early rescue of the New Fourth Army, and said that “without your father, we could not have survived.” Su had at one time served as commander of the first and sixth divisions of the New Fourth Army. (Mao once praised Su’s outstanding military service, saying he should be promoted to Marshal, but Su modestly declined, and therefore was ranked first among the senior generals.) Chen Luwen did not accept the advances of either of these generals, but respected them as her elders. She told me, “They were your fellow Hunanese.”

Chen described Deng Xiaoping as despicable. Comparing Deng to Mao, she said Mao had never deployed troops to attack students, and that he never would have publicly criticized Geng Biao and Huang Hua for “talking rubbish.”[In May 1984, Deng told Hong Kong reporters in Beijing that Geng Biao and Huang Hua had been “talking rubbish” when saying that PLA troops would not be stationed in Hong Kong after the handover of sovereignty.] In the military, Deng sidelined his old comrades from the third guerilla force and promoted his cronies; Marshal Liu Bocheng was a reticent man, and Deng stolehis thunder. Chen said that putting princelings in important positions had in fact been Deng’s idea, and favoritism toward his own protégés was behind the rise of Zou Jiahua, Li Peng and Jiang Zemin. She said Mao was a statesman, but Deng was merely a competent politician. Deng loathed Mao and wanted to pull him off his pedestal, and he purposely set Li Zhisui loose to ruin Mao’s reputation…

I asked her, “Did Mao ever give you any presents?”

She said Mao had given her poems and manuscripts, but she had given them away to others, including more than twenty poems given to Song Renqiong, Jiang Hua, Chen Haosu, Chen Xiaolu, Chen Pixian, Tao Siliang, Yang Dezhi, Su Yu and others. I asked what was in them, and she said she only remembered one sentence: “We’ll meet someday in our dreams.”

She said many senior cadres knew of her relationship with Mao. Some, when they saw her, would kneel and bow and address her as “empress,” asking her to put in a word with Mao on their behalf and let them “rectify bad calls.” She was good friends with Tao Siliang; they were sworn sisters, and she spoke to Mao many times regarding Tao’s father (Tao Zhu), but to no avail. She said Li You (Tao Siliang’s husband, and a writer for Reportage magazine) planned to write her story.

Was the sexual relationship between Chen and Mao casual, or was she a kept woman? I wanted to explore this issue, and every time we met, she would tell me a little more. For example, on March 7, I arranged for veteran journalist Jonathan Mirsky to meet Chen Luwen. We spent more than two hours at the Marriott Hotel buffet. On that day Chen looked radiant in a red suit with a form-fitting skirt. Dr. Mirsky could speak Chinese, so there was no need for an interpreter, and he was well-informed on China issues. I just asked Ms. Chen to speak a little more slowly so he wouldn’t miss anything.

After talking about the three years following her detention in Beijing in 1986, she explained what it was like to work as a dancing partner in Zhongnanhai. She said it was a “political assignment” that began in 1962: the top officials of the central government wanted to dance regularly for their health. That was during a tough period [the end of the famine years]; she was 14 years old and had reached a height of 1.68 meters. Going to Zhongnanhai to dance had the practical benefit of guaranteeing plenty to eat, with fortified flour noodles and delicious sautéed dishes unavailable anywhere else. Their dancehall was under the management of the Air Force political department and the Public Security song-and-dance troupe, and exclusively served the three top leaders, Mao Zedong, Liu Shaoqi and Zhu De. The dance hall held more than 100 people, with orchestral accompaniment, and the girls sat in a row off to one side waiting to be invited to dance.

She said there was a lounge where female performers went in withMao carrying cups of tea, and did not come out for more than an hour. She didn’t know if they went to bed together. There were dance parties twice a week, and each time the dancing went on until three or four a.m., with the troupe members having to get up the next morning for rehearsals and promotional performances. “It was exhausting.” Zhou Enlai’s dance hall was one grade lower, and the dancers were from the Navy political department’s song-and-dance troupe.

Referring to Too Hard to Call You Father [a book published several years earlier by a woman name Ai Bei, suggesting that Zhou Enlai had a daughter out of wedlock], I asked Chen if Zhou had engaged in extramarital affairs. Chen replied without hesitation that Zhou had a lover who was the wife of a general and ten years younger. She was a dancer with the Navy political department’s song-and-dance troupe. Zhou was always telephoning her, and everyone in their circles knew about the relationship. Chen said, “Ai Bei was definitely Zhou Enlai’s daughter!” Ai’s adoptive father was a vice-minister, and her mother was in Beijing; naturally it was all kept secret.

Chen explained that the top officials, apart from the physically frail Chen Yun and the opium-addicted Lin Biao, all fooled around, including Marshals Zhu and Ye and Old Deng. They considered this part of the perks of high office. Some senior officials even had affairs with their daughters-in-law, and complaints were made to Mao.When subordinates wanted to play up to their superiors, introducing them to girls was the most effective method. Someone sent a woman to Mao by chartered plane from Hangzhou, but she wasn’t to Mao’s liking, and he sent her right back. Mao once asked Chen to bring her elder sister to Beijing (Chen came from a family of ten sisters, of which she was the seventh), but she refused. Zhang Yufeng, however, did not refuse to bring her younger sister to Zhongnanhai to wait upon Mao.

Speaking of Mao’s reproductive capacity, Chen said bluntly, “Mao was virile; Dr. Li had to carry out abortions on Mao’s women. It was only in old age that he was no longer able; in the end he couldn’t ejaculate, and only played around to let off steam.” Chen also said that after the Cultural Revolution, Jiang Qing became active in politics and no longer attended to Mao’s sexual needs. She was happy for him to fool around so she could focus her energies on gaining political power.

I noticed that Dr. Mirsky was not reacting to all that Chen said, possibly because she was speaking too fast and he could not understand her clearly. He later asked me why no Hong Kong journalists had followed up on Chen’s story. I replied that it was probably too sensitive; the Hong Kong media had not shown much interest when Dr. Li Zhishui’s book was published, compared with the considerable interest on the mainland. At Chen Luwen’s repeated requests, Dr. Mirsky helped arrange interviews for her at the US and British consulates in Hong Kong. He said the consulate officials had known about her for some time, but their feeling was, why should going to bed with Mao a few times qualify her for political asylum?

Our discussion of Mao’s personal life was most detailed during a conversation at Causeway Bay’s CATIC Plaza. I arrived at 3:40 in the afternoon, ten minutes late, and Chen was already on the corner waiting for me in a white skirt suit and white high heels. She took me to a unit on the sixth floor, which she said she had bought on speculation for HK$9,000 per square foot. Now she was waiting to sell at the best offer. We sat across from each other at a desk, and once she started talking she kept going for half an hour. She said she’d made HK$200 million in arms dealing and property speculation and still had HK$30 million in hand.

I asked her, “After so many years in Hong Kong, why haven’t you remarried?”

She said, “A lot of men pursued me on the mainland; after the Cultural Revolution two members of the Central Committee chased me — it was crazy. After I got to Hong Kong, there was some chairman of the board who was after me, and someone introduced me to the tycoon XXX. I just wasn’t interested. Why should I get a divorce? My relationship with Chairman Mao was too intense, and being with anyone else was just too boring.” As I wrote all this down, I asked her to elaborate.

“As his power grew, his sexual appetite also became more vigorous, even a bit abnormal, and no one could meet all his needs. Mao was a not a normal person, so his sexual appetite wasn’t normal, either. Mao was great in bed; it wasn’t your run-of-the mill sexual intercourse. He was disgusted with Zhou Enlai for pretending to be a saint when he had lots of lovers but was too timid to enjoy it. He was also disgusted with Liu Shaoqi’s pride in being “properly married,” even though it was multiple times – ‘I’m the only one who fools around?’ The best thing about Mao was his honesty; he dared to compare himself to Qin Shihuang.”

“Weren’t Zhang Yufeng and Meng Jinyun enough for him?” I asked.

She said: “The two of them were more ladylike and obedient, but they were prudish and didn’t know how to act. They regarded themselves as objects and didn’t take any initiative, so it was impossible for Mao to be ‘like a fish in water’ with them. I was different, and Mao could call to me in front of them, ‘Chen Huimin, come seduce me away from these books!’”

She didn’t say how she seduced Mao. But she said she always sat reading in the nude in front of him, and when asking Mao a question, she would draw very close to him, and Mao enjoyed the expression in her eyes… It can only be imagined how irresistible the 70-year-old Mao must have found this unclothed dancer, only 18 in 1966. Chen said Mao had a particularly strong sexuality. The first time he forced himself on her, he tore her clothes off and caused her to “collapse in an instant.” After several more of these forced encounters, they became true lovers for whom age was irrelevant. She said Mao’s skin was delightfully smooth and rosy.

She revealed some of Mao’s idiosyncrasies. For example, he liked to take off his trousers and break wind, and he had the women keep track of how many times he did so in the course of a day. He believed that farting was a sign of good health. Mao liked to engage in mutual teasing with Chen, and was not the kind to look only to his own satisfaction. On more than one occasion he had her watch him with other women. She said Mao was thoroughly familiar with the classic Plum in a Gold Vase and said that “imagined eroticism was the best.” He didn’t watch pornographic films — “It was enough to have me at his side. But Jiang Qing watched X-rated films.” She said Mao had a very high sex drive. “Sometimes when I would talk to him about the Cultural Revolution, he’d get angry and say, ‘Don’t pay attention to that bullshit, your business is here.'”

Chen Luwen and Mao discussed Engels’s theory of marriage, which was that monogamy arose from the system of private ownership, and would die out with it. She and Mao both endorsed “communal property and communal marriage.”

According to my notes, I talked with Chen Luwen six times, each times for two or three hours or more. Her chief interest was always publishing her book. She said a lot of people wanted to cash in on her. Someone in Beijing had contacted her and asked her to provide material for the Party history, but she refused. I believe she really did hope to publish a book that would be even more authentic than Li Zhisui’s memoirs, recording her ten-plus years with Mao. She repeatedly explained that the reason she wanted several million US dollars was as compensation for “the ravishment of her youth.” On one occasion she said to me very emotionally, “Mao ruined me — after being with him, I can never be satisfied with another man, and married life is hopeless!” Yet, she did not lack money. What she wanted was fame, and for people to think of her when Mao’s name arose, as the famous concubine Yang Guifei is associated with the emperor Minghuang of Tang.

She was very self-confident, and claimed to have absorbed Mao’s spirit. In fact, it was also Mao’s insufferable arrogance and ignorance that inspired her ambition. She had received “hush money” from the mainland and used it to speculate on the real estate market. She once lost HK$36 million without blinking an eyelash. She angrily berated Britain and the US for treating her like garbage and not letting her immigrate, regarding her as less important than a fugitive student activist. That’s why she wanted to publish a book that would surpass Li Zhisui’s.

She didn’t hesitate to say how much she adored and missed Mao. She said she often dreamed that Mao came to her and said, “As long as you don’t go against me as others have, and only tell the truth about me, I don’t care if it comes out.” She said Mao was a genius, extraordinary and unconventional. Mao was fond of her because she was clever, honest and went against the tide, not only because she was pretty and sexy. Jiang Qing and Mao also had a mutual attraction, and Jiang was absolutely loyal to Mao. Among those close to Mao, “Wang Dongxing was really evil. He did things too horrible for you to imagine.”

She said she didn’t worry about State Security police hunting her down; they had gone to talk with her five times, asking her to return to China and offering her a house, but she refused. But Hong Kong wasn’t safe, and she had to leave. She would go overseas, and she and her son would rely on each other. She predicted that the Maoists would regain power in China someday.

Fourteen years have passed like water in a stream since she talked to me in Hong Kong, hoping I would help her get her memoirs published. Where is she now? How is she doing? In the mighty torrent of a great era, so many prominent people have vanished in a twinkling. Her dream of an epic saga has been reduced to a footnote in the history of tyranny.

What value is there in the story she had to tell? Readers — and those behind the Red Wall — will have to pass their own judgment. At the Tang poem goes, “The white-haired concubine,sitting idly, gossips about the emperor.” It is a new version of an old story.

Hong Kong, September 20, 2011

Published in the October 2011 edition of Open (Kaifang) Magazine

Translated by Stacy Mosher

http://www.open.com.hk/content.php?id=478