1941年12月,太平洋战争爆发后,美国参与对日本的作战。中国抗日战争进入1942年5月,日军切断滇缅公路这条战时中国最后一条陆上交通线后,中美两国被迫在印度东北部的阿萨姆邦和中国云南昆明之间开辟了一条转运战略物资的空中通道,这条空中通道就叫驼峰航线。

得名原因

航线飞越被视为空中禁区的喜马拉雅山脉,下方群山耸立似骆驼峰背,飞机在其间穿行,故此得名。英文为“The Hump”,不能跟“Camel’s Hump”(骆驼峰,位于佛蒙特州的一座山)混淆。

飞行情况

这是世界航空史和军事史上的最为艰险的一条运输线。长约800公里。驼峰飞行也是二战中持续时间最长的大规模空中运输,因恶劣的地形和气候条件,又被称为“死亡航线”。这条航线经过的地区都是海拔4,500到5,500米左右的高峰,最高海拔在7,000米以上。由于当年的飞机设施落后,机上没有加压装置,飞机在异常高空飞行,机员需要有极大的耐力。当时中国航空公司的华人机长陈文宽,及国泰航空创办人之一的Roy C. Farrell亦有驾驶过驼峰航线。

功绩与损失

据美国官方统计,美国空军在1942年4月到1945年8月的援华空运中,为中国空运各类战争物资65万吨。美国空军在驼峰航线上共有超过500架飞机坠毁(包括C-46及C-47),468个美国和46个中国机组牺牲,共计超过1,500人。

“铝谷”

“在天气晴朗时,我们完全可以沿着战友坠机碎片的反光飞行,我们给这条洒满战友飞机残骸的山谷取了个金属般冰冷的名字铝谷。”这是昆明驼峰航线纪念碑下的纪念橱窗中的一段文字,落款是一位驼峰老飞行员。

The Hump

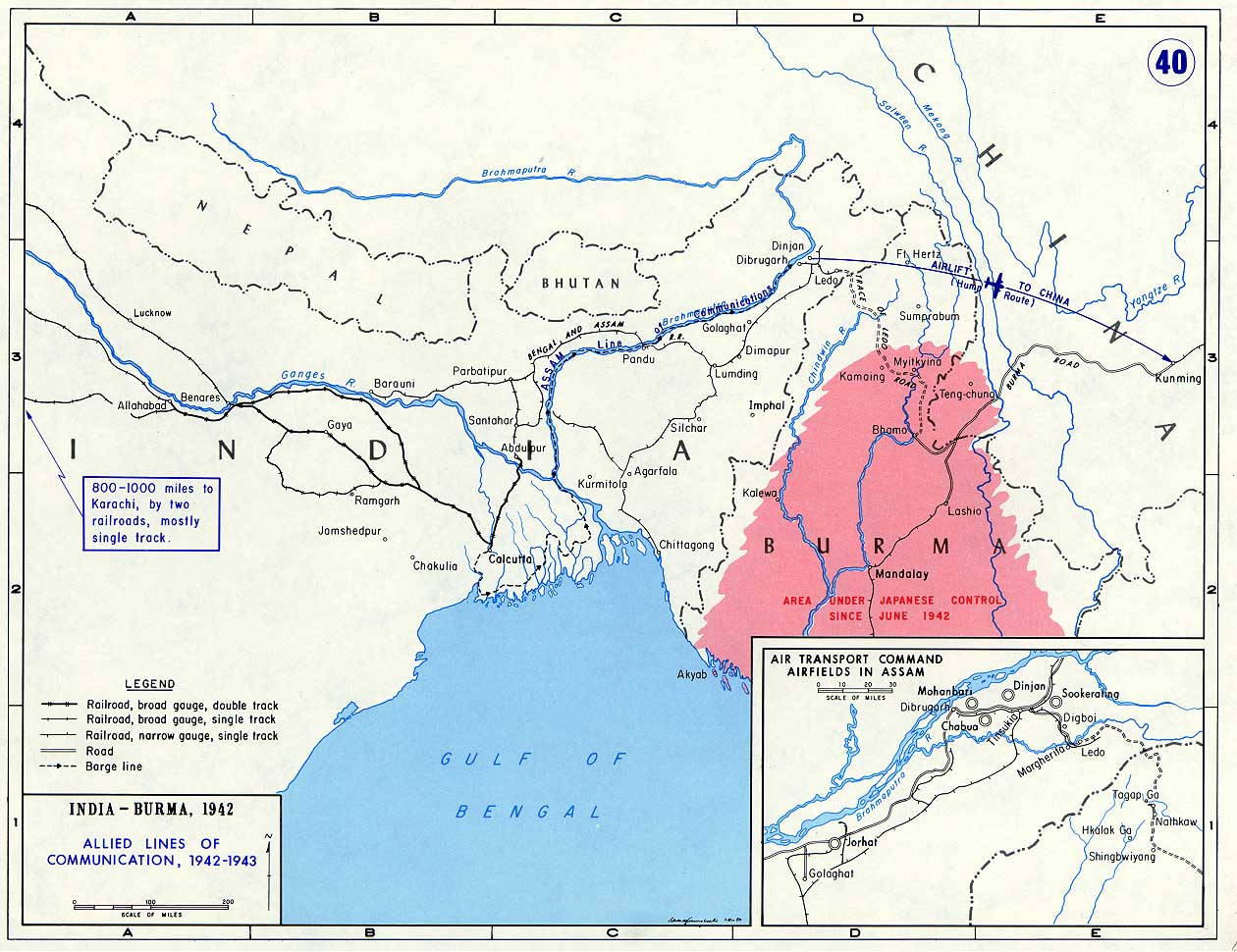

The Hump was the name given by Allied pilots in the Second World War to the eastern end of the Himalayan Mountains over which they flew from India to China to resupply the Flying Tigers and the Chinese Government of Chiang Kai-shek. The region is noted for high mountain ranges and huge parallel gorges, and transverses the upper regions of the larger rivers of South-East Asia: Mekong, Irrawaddy, Salween, etc.

Allied pilots began flying cargo resupply missions over the Hump in April 1942, after the Japanese blocked the Burma Road. Missions continued until near the end of the war, when the Ledo Road opened.

The Burma Road Dilemma

Initially, the Burma Road was used to ferry military supplies, gasoline, and other goods by vehicle to China. However, in April and May 1942, the Japanese seized several areas of Burma that effectively cut Allied access to the Burma Road. To maintain an uninterrupted supply to China of strategic materials requested by the Kuomintang government, U.S. and other allied leaders agreed to organize an continual aerial resupply effort, or air bridge. The U.S. responsibilities were assigned to the United States Army Air Corps, and in July 1942, the USAAF’s new Ferrying Division of the Air Transport Command was assigned the task of organizing the airlift and providing planes and logistical support. The Ferrying Division, commanded by Col. William H. Tunner, assumed the task of organizing the airlift and providing logistical support. Most of the officers, men, and equipment were provided by the USAAF, augmented by British, Indian Army, and Commonwealth forces, Burmese labor gangs, and an air transport section of the Nationalist Chinese Air Company.

Flight Operations

Slowly, an airlift of unprecedented scale began to take shape, transiting the nations of India, Burma, and China. In the west, the air route commenced in India from a series of airfields strung out along the Assam section of the north east Indian railways,[1] and passed over the mountains of Yongnan and a series of spines to Sichuan Province. After the opening of the air bridge, the resupply effort became a literal “road of life” for the Nationalist Chinese war effort. Chiang Kai-shek had argued that at least 7,500 tons per month were needed to keep his field divisions and a 500-plane airforce in operation, though this figure proved unattainable for the first several months of the Hump airlift.[2]

C-54 skymaster

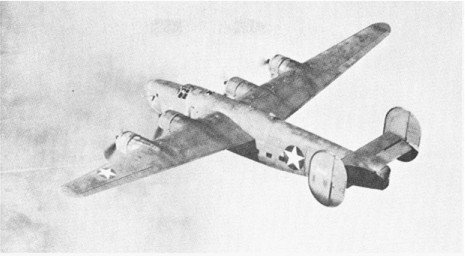

The Consolidated C-87 Liberator Express was a transport derivative of the B-24 Liberator heavy bomber used during World War II.

The Curtiss-Wright C-46 Commando was used as a military transport aircraft

Paratroop C-47, 12th Air Force Troop Carrier Wing.

A United States Air Forces USAAF B-29 Superfortress in flight

A critical problem proved to be finding a cargo transport aircraft capable of carrying heavy payloads at the high altitudes required. Initially the Hump was flown with the C-39, the Douglas C-47, the Douglas DC-3 (converted to carry cargo), and the C-53, a troop transport variant of the C-47. However, these aircraft were ill-suited to high-altitude operation with heavy payloads, and could not normally reach an altitude sufficient to clear the mountainous terrain, forcing the planes to attempt a highly dangerous route through the maze-like Himalayan passes.[3]

The arrival of the Consolidated C-87 Liberator Express and its fuel transport variant, the C-109, in December 1942 boosted tonnage figures, and their high-altitude capability enabled them to surmount the lower mountains (15,000-16000 feet MSL) without resorting to the passes, but the planes had a high accident rate and were unsuited to the airfields then in use. Despite the C-87’s four engines, the planes climbed poorly with heavy loads, and often crashed on takeoff after losing an engine.[4] They also had a unfortunate tendency to spin out of control when encountering mild icing conditions over the mountains.[4] The C-109s were dedicated fuel transport aircraft converted from existing B-24 bombers. All armament and bombardment equipment was removed, and eight fuel tanks were installed inside the fuselage that could carry 2,900 U.S. gallons of high-octane aviation gasoline. Many of the 218 C-109 fuel transports built were sent to the CBI. Like the C-87, they were not popular with their crews, since they were very difficult to land when fully loaded, especially at airfields above 6000 feet in elevation, and often demonstrated unstable flight characteristics with full tanks. A crash landing of a loaded C-109 inevitably resulted in a fireball and crew fatalities.[5]

The Curtiss C-46 Commando began to fly Hump missions in April 1943. The C-46 was a large turbo-supercharged twin-engine aircraft capable of flying faster and higher than any previous twin-engine cargo aircraft, and was capable of carrying heavier loads than either the C-47 or the C-87.[6][7] With the C-46, aircraft loads increased significantly the Hump reached 12,594 tons in December, 1943. Loads continued to increase throughout 1944 and 1945, reaching an all-time maximum tonnage in July, 1945.[8][9]

Flying over the Hump proved to be a nearly suicidal endeavour on the part of Allied flight crews. The air route first crossed the Himalayan foothills and wound its way into the high mountains between north Burma and west China, where violent turbulence, gales, icing, and instrument weather conditions were a regular occurrence. From the beginning, a lack of experienced personnel and resources hampered the mission. In the first months of the operation, inexperienced supply officers often ordered planes loaded until they were ‘about full’, heedless of gross weight limitations. Lack of suitable navigational equipment, radio beacons, and inadequate numbers of trained personnel (there were never enough navigators for all the groups) continually affected airlift operations. While there were some experienced civilian airline and military transport pilots in the ATC, many others were just out of flight school with relatively little instrument time and minimal experience in flying multi-engine cargo planes in extreme conditions. Chinese pilots, while used to a variety of aircraft, also had little instrument flying experience, and most were unfamiliar with the large American transport aircraft used in the airlift. Still, American and Chinese pilots flew their heavily-loaded planes daily on round-trip flights to Chengdu, Kunming, and other cities. Transport planes flew around the clock from any of thirteen bases in northeastern India, landing about 800 kilometres away at one of six Chinese airfields. Some exhausted crews flew as many as three roundtrips every day. Mechanics serviced planes in the open, using tarps to cover the engines during the frequent downpours. There were never enough mechanics or spare parts to go around; maintenance and engine overhauls were often deferred. Many overloaded planes crashed on takeoff after losing an engine or otherwise encountering mechanical trouble. Author and ATC pilot Ernest K. Gann recalled flying into Chabua airfield in India and witnessing four separate air crashes in one day – two C-47s and two C-87s. Three flight crews were killed, all before five o’clock in the afternoon.[10] Due to the isolation of the area, as well as the lower priority of the CBI theater, parts and supplies to keep planes flying were in short supply, and flight crews were often sent into the Himalayan foothills to cannibalize aircraft parts from the numerous crash sites in order to repair the remaining aircraft in the squadron. A byproduct of the tragic, near daily air crashes was a local boom in native wares made from aluminum crash debris.

In addition to losses from weather and mechanical failure, the unarmed and unescorted transport aircraft flying the Hump were occasionally attacked by Japanese Army fighters in the dry (winter) season.[11] While piloting a C-46 on one such mission, Captain Wally A. Gayda returned fire in desperation against a Nakajima fighter by pushing a Browning BAR automatic rifle out the forward crew cabin window and emptying the magazine, killing the Japanese pilot.[12][13] Some 468 American and 46 Chinese flight crews perished from all causes, totaling over 1500 personnel. At times, monthly aircraft losses totalled 50% of all aircraft then in service along the route.

An important development was the capture of Myitkyina airfield in northern Burma in May 1944, by American and Chinese troops of a long-range penentration unit nicknamed Merrill’s Marauders. This deprived the Japanese of the principal airfield from which their fighters patrolled against Allied aircraft flying the Hump. The airfield itself immediately also became a vital emergency landing strip which Allied aircraft could use in case of difficulties, even though fighting continued in the nearby town of Myitkyina until August 1944.

Chinese pilots made a key contribution to Hump flight operations. During 1942 to 1945 the Chinese received from the U.S. exactly 100 transport aircraft: 77 C-47 Dakotas and 23 C-46 Commandos. According to some sources, from May 1942 to September 1945, a total of 650,000 tons were transported via the Hump, of which Chinese pilots accounted for 75,000 tons (about 12%). This figure does not include passengers, of which 33,400 persons were transported, in one or both directions.

In 1944, Air Transport Command was tasked with the mission of supporting B-29 Superfortress missions being flown from China against Japan. From February to October 1944, ATC flew nearly 18,000 tons over the Hump in support of the B-29 strategic offensive bombing campaign, when B-29 operations were transferred from China. In August 1944, USAAF General William H. Tunner took command of the India-China Division of Air Transport Command. By this time, the arrival of increased numbers of Douglas C-54 Skymaster four-engine transport planes greatly increased tonnage levels flown to China from India.[14] In order to improve efficiency, General Tunner changed the C-54’s air routing to a more direct route to China, using escort from Eastern Air Command fighter squadrons to prevent interception by Japanese aircraft. The C-54, which could carry three times the cargo load of the C-47, replaced both the latter transport as well as the C-46 in the last months of the airlift.[15]

The Hump’s air bridge operation continued until the end of the war. Though it declined in importance with the opening of the Ledo Road network in January 1945 and in particular, the recapture of Rangoon, the airlift’s total tonnage (650,000 tons) dwarfed that of the Ledo Road (147,000 tons).[16] The final summary of flight time in the airlift totalled 1.5 million flight hours. The Hump ferrying operation was the largest and most extended strategic air bridge in the world, only exceeded in 1949 (in volume of cargo airlifted) by the West Berlin air bridge.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Hump