/**这是从网络上检索到的CBC电视台2008年6月的一篇有史料价值的新闻报道。1973年5月1日,中加两国建交后首批中国公派留学生5男4女前往加拿大,留学渥太华的Carleton大学,本文作者Ira Basen当时正在该校寻找暑期工作,于是,便与这些留学生有了接触。本文主要讲述作者与卢树民大使之间的故事。。。jack注**/

Exit interview

China and the West

A Chinese ambassador’s unique Canadian experience

Last Updated: Monday, June 2, 2008 | 7:20 PM ET

By Ira Basen CBC News

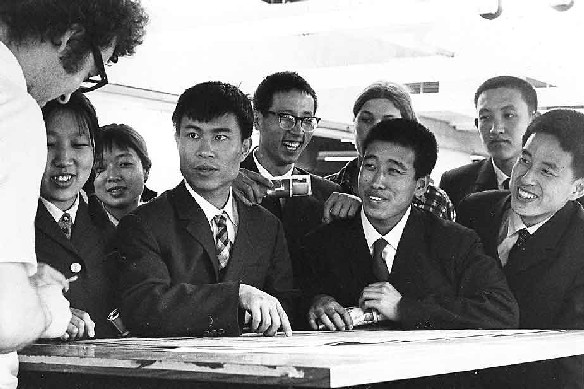

(China’s first foreign exchange students to Canada, in 1973: (L-R) Ma Hui-Yun, Yuan Hsiao-Ying, Cheng Kang, Lu Shumin (with glasses who would become Beijing’s ambassador to Canada), Chang Yun, Zhang Yuan-Yuan and Mei Chiang Chung. )

It was the summer of 1973 and the slumbering Chinese giant was slowly awakening. At home, the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution was in its seventh year. Many of its murderous excesses were still to come. Internationally, China was beginning to open its doors to the world.

In this, Canada was leading the way. It officially recognized the People’s Republic in the fall of 1970. Fifteen months later, U.S. President Richard Nixon made his surprise visit, unexpectedly toasting Chinese leaders in Beijing’s Great Hall of the People.

Then, on May 1, 1973, nine Chinese students arrived at Ottawa’s Uplands airport and made history. They were the first students from Communist China to ever study at a North American university.

(Ira Basen, centre, with two of China’s first foreign exchange students in Ottawa in 1973: Zhang Yuan-Yuan (left) and Yuan Hsiao-Ying. )

In an exchange agreement, nine Chinese students would study in Canada and a group of Canadian students would be given the extraordinary opportunity to attend university in China.

Carleton University was the chosen destination for the Chinese students, possibly so they could not stray too far from the watchful eye of the embassy in Ottawa.

I was an undergraduate student at Carleton in 1973, looking for a summer job, and while I knew almost nothing about China, I was fortunate enough to be hired by the university to help these exchange students get acclimatized to Canadian life and prepare for the academic year to come.

It was an experience that changed all our lives.

Stereotypes undone

Like most Canadians, the only image I had of Chinese students then was of the millions of fanatic young people roaming the countryside holding high their little red books containing the collected wisdom of Chairman Mao and railing against “capitalist roaders.”

But these students, five men, four women, all in their early 20s, were nothing like the stereotypes, except perhaps for their clothes. Their baggy, blue cotton “Mao jackets” or more formal suits and ties caused them to stand out wherever they went in Ottawa that summer.

Clearly, their selection was not random. They were all bright, reasonably proficient in English and had participated in the Cultural Revolution, spending time working in the countryside with “the people.” But they were also modest, unfailingly polite, eager to learn and, while supportive of their government, relatively apolitical and candid about the failings of their own economy.

We spent the summer attending lectures on history, literature, art, economics and philosophy, and discussing ideas they had never been exposed to. We went to movies, art galleries, museums and concerts and learned the intricacies of eating Western food with a fork in a university cafeteria.

Their lack of knowledge about the West was occasionally staggering. In the summer of 1973 they were still unaware that a man had walked on the moon four years earlier.

Several months later, I went off to graduate school and lost track of these students, though I often wondered what became of them. That question was answered a couple of years ago when I saw that one of them, Lu Shumin, was back in Ottawa. This time, though, he was the Chinese ambassador to Canada.

Ambassador Lu

It turns out Lu had returned to Ottawa once before, in the late 1970s, to work as a translator at the Chinese embassy. He then began his climb up the diplomatic ladder, with postings in Australia and Washington, before becoming the ambassador to Indonesia in 2002.

(Lu Shumin, the ambassador to Canada from the People’s Republic of China in a November 2006 photo. (Jonathan Hayward/Canadian Press))

Three years later, he was back in Ottawa, this time to oversee the embassy that had overseen him 30 years earlier. It should have been a relatively easy posting, a chance to reconnect with old friends and oversee a now burgeoning trade relationship between the two countries. But it didn’t quite work out that way.

When Stephen Harper became prime minister in February 2006, he ended years of quiet, behind-the-scenes diplomacy with China by openly declaring that he would not sell out those fighting for human rights “to the almighty dollar.”

Harper’s government publicly clashed with the Chinese over Tibet, Taiwan and imprisoned dissident Huseyin Celil as well as the persecution of the religious sect Falun Gong. The prime minister even declared in Parliament that there were a thousand Chinese government agents in Canada involved in industrial espionage, a charge angrily denied by the embassy.

Exit interview

Two months ago, relations hit a new low as many Canadians were outraged by the scenes of Chinese troops cracking down on supporters of the Dalai Lama on the streets of Tibet.

The Harper government condemned the Chinese administration. At the Chinese embassy in Ottawa, ambassador Lu responded with a public relations offensive of his own that was extraordinary for a Chinese diplomat: He made himself available for interviews to the Canadian media and even invited reporters to the embassy for a news conference where he railed against the “Dalai clique” and the Tibetan “splitists,” whom he compared to the Nazis.

He came across as an articulate but not particularly sympathetic defender of the Chinese position.

A few weeks later, the Chinese government announced that Lu Shumin’s time in Canada was coming to an end. One Ottawa newspaper announced the news with the headline “Embattled Chinese Ambassador Lu Shumin to Return Home.”

(Lu Shumin, far right, as an exchange student with the Kealey family of Ottawa in 1973. He would later become China’s ambassador to Canada. (Courtesy Kealey family) )

I had visited with Lu a couple of times since his return to Ottawa and when I heard about his impending departure I asked him if he would care to do an “exit interview,” to reflect on the end of his 35-year association with Canada.

He didn’t appear “embattled” when I met him late one afternoon at the embassy in Ottawa in early May 2008. Earlier in the day he had been honoured at a luncheon hosted by the federal minister of international trade, David Emerson, where all the correct words were exchanged. Public Safety Minister Stockwell Day had attended a farewell reception at the embassy just the previous week.

Lu said his departure was simply part of the normal diplomatic rotation and not related to his problems with the Canadian government or his openness with the press. As a diplomat, you have to be prepared to pull up stakes every few years, he said. But he admitted that this move left him with feelings of “sweet sorrow.

“I feel very satisfied that I have very many friends here and that is the most precious thing I cherish.”

Crossing centuries

I asked Lu what stood out about his arrival in Ottawa 35 years earlier. His reply was that he and the other students felt as if they had arrived in a different universe, so great were the differences between 20th century urban Canada and what was effectively still a 19th century peasant society.

Even crossing an Ottawa street back then was an adventure. “When you looked at people here living in much larger houses and they could go anywhere in their cars, that was certainly a striking contrast. Back home we were all on bicycles and a home was maybe one room with three generations of a single family all under one roof or maybe in one or two rooms.”

By the time Lu returned to Canada in 2005, the streets of Ottawa had gotten busier, but the changes here were insignificant compared to the transformation that China had undergone.

The capitalist roaders who had been denounced during the Cultural Revolution were now being hailed as economic saviours. And that was not all that was different.

“I can remember when I was in Carleton,” he recalls, “we would go to the grocery store to buy something. There were some things made in China but it was always low grade. But now it’s different. You go to the shops and if you want to find something that is not made in China it is very difficult and the quality is high grade.”

Lu is clearly proud of the economic progress China has made over the past three decades. But he also understands it has resulted in some significant changes in the way Canadians view his country.

In the 1970s, it was easy for people in Canada to cheer for the Chinese, to hope that out of all their political turmoil they would find a way to provide food, clothes and shelter for hundreds of millions of people living in abject poverty.

But now that China has become an economic powerhouse, it is often no longer seen as the sympathetic underdog. Instead, many here see it as contributing to Canada’s economic woes, a low-wage magnet attracting manufacturing jobs once held by Canadians.

The good life

Lu Shumin thinks that criticism, as well as many of the others levied against China today, is unfair.

Time and again he returns to the same two refrains: The first is that there can be no double standard. Canadians cannot argue that it is okay for them to have high-paying jobs and drive their cars wherever they want while denying the same rights to the Chinese.

And second, Canadians are uninformed about his country. If they would take the time to learn the facts about Tibet, Darfur, the environment, human rights and all the rest, they would arrive at different conclusions, he argues.

I suggest to him that one of the things that Canadians find most puzzling about China today is how the government seems to overreact to almost every situation.

Neither the Dalai Lama nor Taiwan nor Falun Gong appears to pose any real threat to the Chinese leadership, yet Beijing behaves in every case as if it did. “It’s like hitting a fly with a sledgehammer,” I tell him.

He responds that a better understanding of Chinese history and development might lead me to the opposite conclusion, that China continues to be threatened by forces that are trying to destroy it and that the government must protect the human rights of the majority by dealing firmly with those groups who are trying to tear the country apart.

“But,” I ask him, “isn’t the tough response out of proportion to the actual threat?”

He smiles, “There was a riot after the hockey game in Montreal and even the police had to come out and arrest the rioters. Do you think that is kind of tough? I think it is not whether it is tough or not, it is law enforcement and the measures taken by the government were appropriate to what has happened.”

Goodbye to the past

After our interview ended, Lu presented me with a Beijing Olympic pin. Three days later, he and his wife, whom he met 30 years ago while she was an exchange student at York University, left Ottawa for the Special Administrative Region of Macao, where Lu was to take up his new posting.

His return to Ottawa had clearly not gone as smoothly as he had anticipated. It’s unlikely he will ever be back in any official capacity.

He had arrived in the 1970s amidst the heady optimism of China’s opening up to the world. He leaves this time having experienced the more sober realities of the political and economic differences that have emerged between the two countries.

His relationship to Canada was unique. Most diplomats come to Ottawa with only a passing knowledge of this country and its people. Lu Shumin was different.

This was, in many respects, his second home, a place where he had his eyes opened to the possibilities of the Western experience.

He readily acknowledges that he will miss us. The many Canadians he befriended over the past 35 years will clearly miss him as well.

Liberal prime minister Pierre Trudeau meets Mao Zedong, China’s ultimate leader, in October 1973 during China’s historic opening to the West. (Associated Press)

http://www.cbc.ca/canada/story/2008/05/20/f-vp-basen.html