(Canadian Infantrymen, Hong Kong.)

The Battle of Hong Kong

December 8-24, 1941

Casualties

Country Killed Total

Canada 554* 1,050

Britain ? ?

India ? ?

*Approximately 290 Canadian soldiers were killed in battle and, while in captivity, approximately 264 more died as POWs, for a total death toll of 554.

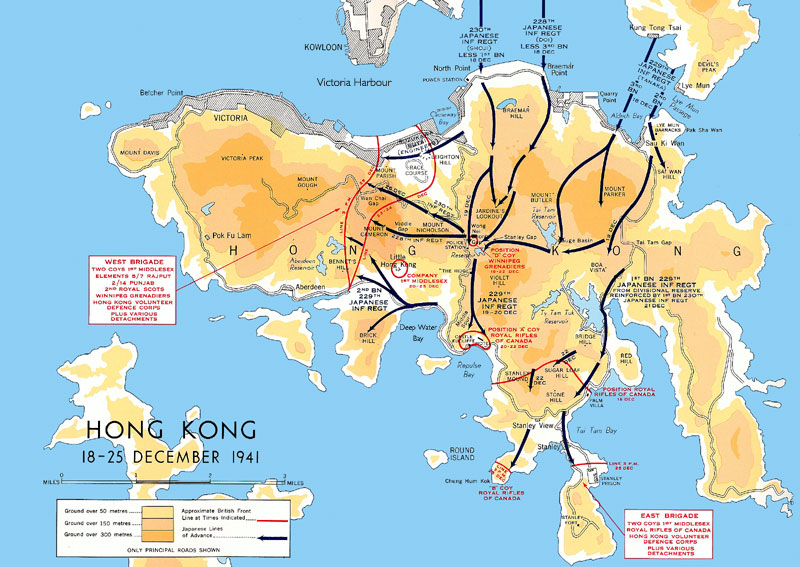

Map

Overview

On 8 December 1941, a day after the its Air Force had devastated the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbour, the Japanese Empire launched an attack on the Britsh Crown Colony of Hong Kong.

In the ensuing battle, the Royal Rifles of Canada and the Winnipeg Grenadiers – the first Canadian ground units to see action in the Second World War—fought valiantly to defend the colony. Initially, the Grenadiers were dispatched to the Gin Drinkers’ Line, a chain of defenses in the New Territories on the Chinese Mainland, to hold back the onslaught. But heavy air raids and artillery attacks forced the Commonwealth troops to withdraw from the New Territories to their garrison on the island of Hong Kong. After several days of heavy bombardment, the Japanese stormed the island’s northern beaches on the night of 18 December.

The Japanese, well-supported from the air and reinforced from the Mainland, quickly separated the British East and West brigades, thus severing the Canadian contingent into two. With both brigades isolated, it was only a matter of time before the Island would fall. Still, the Canadian defenders fought on in the face of the relentless Japanese assault and suffered heavy casulaties. On Christmas Day, the Canadians were forced to surrender; those who survived would have to endure three and a half years of hardships as prisoners of war.

Introduction

In the Second World War, Canadian soldiers first engaged in battle while defending the British Crown Colony of Hong Kong against a Japanese attack in December, 1941. The Canadians at Hong Kong fought against overwhelming odds and displayed the courage of seasoned veterans, though most had limited military training. They had virtually no chance of victory, but refused to surrender until they were overrun by the enemy. Those who survived the battle became prisoners of war (POWs) and many endured torture and starvation by their Japanese captors.

In October 1941, the Royal Rifles of Canada and the Winnipeg Grenadiers were ordered to prepare for service in the Pacific. From a national perspective, the choice of battalions was ideal. The Royal Rifles were a bilingual unit from the Quebec City area and, together with the Winnipeg Grenadiers, both battalions represented eastern and western regions of Canada. Command of the Canadian force was assigned to Brigadier J.K. Lawson. This was also a good choice because of Lawson’s training and experience; he was a “Permanent Force” officer and had been serving as Director of Military Training in Ottawa. The Canadian contingent was comprised of 1,975 soldiers, which also included two medical officers, two Nursing Sisters, two officers of the Canadian Dental Corps with their assistants, three chaplains, two Auxiliary Service Officers, and a detachment of the Canadian Postal Corps. There was also one military stowaway who was sent back to Canada.

Prior to duty in Hong Kong, the Royal Rifles had served in Newfoundland and Saint John, New Brunswick while the Winnipeg Grenadiers had been posted to Jamaica. In these locations, both battalions had received only minimal training. In late 1941, war with Japan was not considered imminent and it was expected that the Canadians would see only garrison (non-combat) duty. Instead, in December, the Japanese military launched a series of attacks on Pearl Harbor, Northern Malaya, the Philippines, Guam, Wake Island and Hong Kong. The Royal Rifles and the Winnipeg Grenadiers would find themselves engulfed in hand-to-hand combat against the Japanese 38th Division.

The Invasion

The Japanese attack did not take the garrison by complete surprise; the defence forces were prepared. On the morning of December 7, the entire garrison was ordered to war stations. The Canadian force was ferried across from Kowloon to the island, and by 5 p.m. the battalions were in position and Brigadier Lawson’s headquarters was set up at Wong Nei Chong Gap in the middle of the island. Fifteen hours before the Japanese attacked, all Hong Kong defence forces were in position.

On December 8, at 8 a.m., Japanese aircraft attacked the Kai Tak airport and easily damaged or destroyed the few aircraft of the Royal Air Force. The nearly-empty camp at Sham Shui Po was the next target, where two men of the Royal Canadian Signals were wounded. They were the first Canadian casualties in Hong Kong.

Wong Nei Chong Gap, scene of one of the fiercest encounters in the battle for Hong Kong. Here a company of the Winnipeg Grenadiers held out for several days and inflicted much delay and many casualties upon the Japanese. The Island’s main north-south road runs from right to left across the picture.

That same morning, the Japanese ground forces moved across the frontier of the New Territories and met resistance from the forward forces of the Mainland brigade. In the face of strong enemy pressure these advance units fell back to the “Gin Drinkers’ Line”. The defenders hoped to defend the line for a week or more but, on December 9, the Japanese captured Shing Mun Redoubt, an area of high ground and the most important strategic position on the left flank of the Gin Drinker’s Line. The Japanese had launched their attack under cover of darkness and there was fierce fighting, but in the end the Japanese were victorious. Their victory at night revealed how General Maltby had completely underestimated his enemy. In a dispatch he had noted that “Japanese night work was poor.” But within hours of their first attack, Shing Mun Redoubt was in enemy hands.

On December 10, “D” Company of the Winnipeg Grenadiers was dispatched to strengthen the remaining defenders on the mainland. On December 11, this company exchanged gunfire with the enemy and became the first Canadian Army unit to engage in combat in the Second World War.

Further Japanese attacks followed and the “Gin Drinkers’ Line” could no longer be held. Midday on December 11, General Maltby ordered the mainland troops to withdraw from the mainland. The Winnipeg Grenadiers covered the Royal Scots’ withdrawal down the Kowloon Peninsula. The Punjabs moved at night and the Rajputs, who had been left to guard Devil’s Peak, followed. The evacuation was successful and most of the Brigade’s heavy equipment was saved.

On December 13, a Japanese demand for the surrender of Hong Kong was categorically rejected.

The Defence of the Island

On the island, the defending forces were reorganized into an East and West Brigade. The West Brigade, commanded by Brigadier Lawson, consisted of the Royal Scots, the Winnipeg Grenadiers, the Punjab unit and the Canadian signallers. The East Brigade, under Brigadier Wallis, comprised the Royal Rifles of Canada and the Rajput unit. The Middlesex Regiment was directly under General Maltby’s command at Fortress Headquarters.

The Canadian battalions were divided and the Royal Rifles were no longer under Brigadier Lawson’s command. But ironically, both Canadian units were still charged with defending the southern beaches, where General Maltby mistakenly feared a seaborne attack.

The boundary between the brigades ran just east of the central north-south road across the island. Brigadier Lawson maintained his headquarters at Wong Nei Chong on this key road cutting through the island. Brigadier Wallis established his headquarters at Tai Tam Gap, a central position in the eastern sector.

To soften the island’s defences, the Japanese directed heavy artillery bombardment at the island, mounted destructive air raids, and systematically shelled the pillboxes along the north shore.

On December 17, the Japanese repeated their demand for surrender. Once again it was summarily refused, but the situation was very grim. With the sinking of two British relief ships off Malaya and the crippling of the United States fleet at Pearl Harbor, there was no hope of relief, and the Chinese armies were in no position to give immediate aid. The defenders awaited assault in complete isolation. Brigadier Wallis visited the Rajput Regiment’s headquarters on December 18, and wrongly assured the Indian military personnel that the Japanese would not attack. Like General Maltby, he grossly underestimated the fighting ability of the Japanese.

The Attack on the Island

The invasion came with nightfall on December 18. The enemy launched four separate amphibious assaults across a three-kilometre front on the northern beaches of Hong Kong Island. They came ashore in the face of machine-gun fire from soldiers of the Rajput unit who were manning the pillboxes.

From the shore, the Japanese forces fanned out to the east and west and advanced up the valleys leading to high ground. The Royal Rifles engaged the invading Japanese and tried to push them back. “C” Company of the Royal Rifles, in reserve in an area adjacent to the landing, counter-attacked throughout the night, suffering and inflicting heavy casualties. Other platoons of the Royal Rifles went into action on the west side of Mount Parker and suffered many casualties from the already-entrenched enemy.

The strength of the invasion force was overwhelming, and by early December 19, the Japanese had reached as far as the Wong Nei Chong and Tai Tam Gaps, again proving their effectiveness at night fighting.

The East Brigade

With the enemy well established on the high hills from Mount Parker to Jardine’s Lookout, General Maltby ordered the East Brigade to withdraw southwards towards Stanley Peninsula where, it was hoped, a counter-attack could be made.

By nightfall, on December 19, a new defensive line was established from Palm Villa to Stanley Mound, and a brigade headquarters was set up at Stone Hill. Unfortunately, some valuable mobile artillery was destroyed during the withdrawal. Even worse, vital communications were severed between the East and West Brigades when the advancing Japanese reached the sea at Repulse Bay.

The Brigade was now seriously reduced in numbers, with the Rajput Battalion being virtually wiped out defending the northern beaches. The East Brigade consisted of the Royal Rifles, some companies of the Volunteer Defence Corps and some Middlesex machine-gunners. The Royal Rifles were exhausted. Deprived of hot meals for several days, they had to catch whatever sleep they could in the weapon pits which they were continually manning. Yet, during the next three days, these men valiantly drove northward over rugged, mountainous terrain to join with the West Brigade, or to clear the Japanese from the high peaks.

First, they attempted a thrust along the shore of Repulse Bay in the hope of reaching Wong Nei Chong Gap – and the West Brigade. They managed to drive the enemy out of an area around the Repulse Bay Hotel. However, they were unable to dislodge the Japanese from the surrounding hill positions and were forced to withdraw. One company of the Royal Rifles was left to hold this area and a renewed effort to break through was made on December 21. Next came an attempt to reach Won Nei Chong by a more easterly route. Despite heavy enemy opposition south of Tai Tam Tuk Reservoir, the Royal Rifles succeeded in driving the Japanese out of a number of hill positions and in destroying a group holding the crossroads south of the reservoir.

Again the attack could not be maintained. The companies had become separated and they were out of mortar ammunition. The enemy was still pushing and Brigadier Wallis decided to withdraw his men to their former positions.

Fighting at Repulse Bay continued, but despite a valiant effort, the defenders had to be withdrawn.

After December 21, no further attempts were made to drive northward, for the troops were depleted and exhausted and the Japanese, who had been reinforced, mounted constant attacks.

At noon on December 22, the Japanese took Sugar Loaf Hill, but volunteers from the Royal Rifles’ “C” Company went forward and by nightfall they had recaptured the hill. Another company, however, was driven from Stanley Mound.

On the evening of December 23, orders were given for a general withdrawal to Stanley Peninsula. The exhausted Royal Rifles were taken out to Stanley Fort, well down the peninsula, for a rest. However, they were soon recalled for action as the Japanese were making advances which the Volunteer Defence Corps and other available troops could not contain.

The Royal Rifles celebrated Christmas Day, 1941, by returning to battle. Brigadier Wallis ordered a counter-attack to regain ground lost the night before. “D” Company was successful in this mission but suffered heavy casualties.

The West Brigade

The Winnipeg Grenadiers had also been thrust swiftly into action with the West Brigade.

On December 18, the Brigade consisted of the Winnipeg Grenadiers, the Royal Scots in reserve in the Wan Chai Gap-Mount Parish area, the Punjab Battalion in Victoria City, and a company of the Middlesex around Leighton Hill.

Charged with covering the southwest and west coasts of the island, the Grenadiers established their headquarters at Wan Chai Gap. Their “D” Company was back in Brigade Reserve at Wong Nei Chong. To be ready for action at a moment’s notice, “flying columns” were organized from the Headquarters Company and were billeted just south of Wan Chai Gap.

When the enemy landed on the evening of December 18, the flying columns were ordered forward. Two platoons were directed at Jardine’s Lookout and Mount Butler, where they engaged the Japanese in intense fighting. Heavily out-numbered, they were cut to pieces and both platoon commanders were killed.

Early in the morning of the 19th, “A” Company of the Grenadiers was ordered to clear Jardine’s Lookout and to push on to Mount Butler. Reports of its action are confused – so many officers and men became casualties – but it apparently became divided and part of the company, led by Company Sergeant-Major (CSM) J.R. Osborn, drove through to Mount Butler and captured the top of the hill. A few hours later, a heavy counter-attack forced this party back where it rejoined the rest of the company. Then, while attempting to withdraw, the whole force was surrounded.

The Japanese began to throw grenades into the defensive positions occupied by “A” Company of the Grenadiers, and CSM Osborn caught several and threw them back. Finally one fell where he could not retrieve it in time. Osborn shouted a warning and threw himself upon the grenade as it exploded, giving his life for his comrades. Shortly afterwards, the Japanese rushed the position and “A” Company’s survivors became prisoners. At the end of the War, CSM J.R. Osborn was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross.

As the Japanese approached the West Brigade Headquarters, Brigadier Lawson decided to withdraw to a new location. However, before the action was completed the headquarters was surrounded. A company of Royal Scots attempted to provide assistance, but less than a dozen were able to get through. About 10 a.m. on December 19, Brigadier Lawson reported to Fortress Headquarters that he was going outside to “fight it out” with the enemy who were firing into the shelter at point-blank range. He left the bunker with a pistol in each hand to take on the massed enemy, losing his life in the effort.

After Brigadier Lawson’s death, and that of Colonel Hennessy, who was next in command, West Brigade was without a commander until Colonel H.B. Rose of the Hong Kong Defence Corps was appointed on December 20.

Meanwhile, “D” Company of the Grenadiers held on firmly to its position near Wong Nei Chong Gap, denying the Japanese use of the one main north-south road across the island. The Grenadiers inflicted severe casualties on the enemy and delayed Japanese advances for three days. They held out until the morning of December 22, when ammunition, food and water were exhausted and the Japanese had blown in the steel shutters of the company shelters. Only then did they surrender. Inside were 37 wounded Grenadiers.

The final phase of the fighting on the western part of the island consisted of a brave attempt to maintain a continuous line from Victoria Harbour to the south shore. The Winnipeg Grenadiers were sent to hold Mount Cameron, an important height in the line, and they did so despite intense dive-bombing and mortar attacks. On the night of December 22, they were forced to retreat as the Japanese once again struck in the darkness.

Now the line consisted of the Middlesex Regiment and the Indian battalions on the left, the Royal Scots on the western slopes of Mount Cameron, and the Grenadiers in the right sector to Bennet’s Hill. On the afternoon of December 24, the left sector fell and the enemy made further gains on Mount Cameron. The Grenadiers held their positions against heavy attacks and on Christmas morning regained some ground lost at Bennet’s Hill.

However, after a three-hour truce the Japanese again attacked. The Allied positions were overrun and the defenders were forced to surrender.

At 3:15 p.m. Christmas Day, General Maltby advised the Governor that further resistance was futile. The white flag was hoisted. On the east side of the island, a company was just moving forward for an attack when word of the surrender arrived.

After seventeen and a half days of fighting, the defence of Hong Kong was over. The battle-toughened Japanese were backed by a heavy arsenal of artillery, total air domination, and the comfort of knowing that reinforcements were available. In contrast, the defending Allies, with only non-combative garrison experience, were exhausted from continual bombardment, and had fought without relief or reinforcement.

The fact that it took the Japanese until Christmas Day to force surrender is a testimony to the brave resistance of the Canadian and other defending troops.

Aftermath

The fighting in Hong Kong ended with immense Canadian casualties: 290 killed and 493 wounded. The death toll and hardship did not end with surrender.

Even before the battle had officially ended, Canadians would endure great hardships at the hands of their Japanese captors. On December 24, the Japanese overran a makeshift hospital in Hong Kong, assaulting and murdering nurses and bayoneting wounded Canadian soldiers in their beds. After the colony surrendered, the cruelty would continue. For more than three and a half years, the Canadian POWs were imprisoned in Hong Kong and Japan in the foulest of conditions and had to endure brutal treatment and near-starvation. In the filthy, primitive POW quarters in Northern Japan, they would often work 12 hours a day in mines or on the docks in the cold, subsisting on rations of 800 calories a day. Many did not survive. In all, more than 550 of the 1,975 Canadians who sailed from Vancouver in October 1941 never returned.

Last updated on Oct 13, 2006

http://wwii.ca/content-42/world-war-ii/the-battle-of-hong-kong/

The Winnipeg Grenadiers, Hong Kong. Dec 6-25 1941

The unit whose actions will be followed and analyzed in this paper is the battalion of the Winnipeg Grenadiers during their two week struggle in the battle for Hong Kong 1941 against elements of the Japanese Imperial Army. The battle only lasted from the 8th of December with the initial Japanese attacks on the mainland forces defending Kowloon to Christmas day when Major General C.M. Maltby surrendered the remaining Commonwealth forces that were still attempting to hold the island. The Canadian battalions, the Winnipeg Grenadiers and the Royal Rifles, accounted for the bulk of the fighting and of the 1 975 men who embarked for Hong Kong from Vancouver only 1 418 survived the battle and subsequent years as Japanese POWs.

Were these losses then worth the gain? The hard part about this question is trying to come up with any sort of gain at all from the battle. It has been argued that their sacrifice slowed the Japanese invasion of the Pacific islands and that the better part of a division had been put out of action. These claims are, if examined dispassionately, quite ridiculous and seem to be clutching at straws to explain what was in reality a military disaster. What then must be looked at is the performance of individual units within the context of defeat. How well did they fight? Did they indeed inflict reasonable casualties on the enemy? How did their officers and NCOs perform?

Avoiding the political decision-making process that sent the two Canadian battalions to their destruction and focusing just on the Winnipeg Grenadiers, the examination of the unit that was sent begins with them as a garrison unit in Jamaica. The Grenadiers were formed in 1908 as a militia unit and were raised to become the 11th battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. When World War Two began in Europe they were one of the first units to be mobilized and by October 1939 they were up to full battalion strength. The officer commanding was Lt. Col J.L.R. Sutcliffe a veteran of the First World War who served in France, Belgium, India, Mesopotamia, Persia, Russia and Turkey. The second in command was Major G. Trist, also a veteran. Both officers were viewed as ‘useful and competent’. The unit was originally designated a machine gun battalion but in 1940 was converted to a rifle battalion. They were put into garrison duty for sixteen months in Jamaica and during this time they had only two weeks of training at Montpelier Camp and not a single round was fired in training. In October of 1941 they were returned to Canada and warned immediately about over-seas duty

While in Winnipeg the men got to fire off thirty-five rounds each from their rifles for practice. The unit was also under strength for front line duty but they received 436 new men including 63 who did not even have their sixteen weeks basic training yet. There also was no training what-so-ever with any heavy weapons. A standard battalion in 1941 should have included twenty-one Universal Carriers and thirty-seven 1500 lb weight trucks. The unit sent had six carriers and twelve trucks. Of the other approximately eighty vehicles standardly assigned to a battalion there was to be no sign as the battle ended before they could arrive. Of the twenty-two Boys anti-tank rifles they were supposed to have the battalion had one. The Grenadiers actually had their mortars but did not have any ammunition for them at all. Despite these shortcomings the force set sail on October 27th with a total of ( between both battalions ) 1 975 men and arrived in Hong Kong on the 16th of November.

The Commanding Officer in Hong Kong was a British Major General C.M. Maltby. He commanded a force of 5 422 infantry and approximately 6 000 other possible combatants. Most of the Island’s defenses were set up to repel an invasion by the sea with large coastal batteries and armor-piercing shells for the guns. Maltby’s initial plan was to hold a thin line of defenses known as the Gin Drinkers Line with three battalions who would delay any attack on the Island itself as well as cover the demolition teams that would be sent out to blow up all the usable bridges in the route of advance. The Line was eleven miles long and realistically required around seven battalions to hold it. Back on the Island a second brigade of three battalions was formed under the command of Canadian Brigadier Lawson and this included the Winnipeg Grenadiers. The Gin Drinkers Line was supposed to hold for at least seven days.

The Japanese force facing the Line consisted of the 38th division of the 23rd Army with three regiments of infantry, the 228th, 229th and 230th. Backing this up was the 38th Mountain Artillery regiment, the 38th Engineering regiment and attached were two more Independent Mountain Artillery regiments, two anti-tank gun battalions, a mortar battalion, another engineering regiment, three transport regiments and two river crossing companies. The 23rd Army also made available their Army level artillery of heavy guns, two more Independent Artillery battalions and 40 Kawasaki Ki 32 single-engine bombers.

On December 6th Maltby issued a warning to all units to stand to their war positions. The Grenadiers ferried over to Hong Kong Island from their barracks at Kowloon in the morning of the 7th. Early on the 8th they were informed that they were at war now with Imperial Japan. The Japanese hit the Gin Drinkers Line on the afternoon of the 9th and almost immediately the Line began to fold. The Grenadiers sent company D over from the Island to act as a reserve but were never employed and went back to the Island on the 11th after only experiencing scattered artillery and small arms fire which caused no casualties. By the 13th the mainland had been completely abandoned.

The Island was broken into two commands. The East under Brigadier Wallis consisting of the Royal Rifles and the Rajputs and the West under Lawson with the Winnipeg Grenadiers, Punjabs and the Royal Scots. The Middlesex were scattered about the Island holding all of the static positions on the coast. The Grenadiers were stationed in the south-west and centre of the Island.Between the 14th-17th they experienced very little activity beyond shelling and air strikes. A company was at Little Hong Kong, B company at Pok Fu Lam, C company at Aberdeen, D company at the Wong Nei Chong Gap acting as brigade reserve, and battalion HQ was in the Wan Chai Gap in the centre of the Island.

On the 18th the Japanese assault began on the Island. The initial landing obliterated the Rajputs then hit the Royal Rifles and forced them south. The first action for West brigade came when Lawson sent three platoons ( one from each A, B & C companies – his reserve ‘flying column’ ) to set up road blocks at strategic points. Lt. Birkett went to Jardine’s Lookout where he was killed covering his units withdrawal when they discovered the position already occupied by the quickly moving Japanese. Lt. French went to Mt. Butler to also find the Japanese already there but he counterattacked them, took the hill, could not hold it for long, and was forced to withdraw when he too was killed. The 3rd platoon disappeared after being sent to a road junction to the north-west of the Gap.

Major Gresham was ordered with A company and a platoon of D company to re-take Jardine’s Lookout and Mt. Butler. This was done by dawn but a number of heavy Japanese counterattacks forced them off the hill and by mid-afternoon they were surrounded. During their last stand Company Sergeant Major J.R. Osborn deliberately covered a grenade with his body to save his men and was killed. He received the Victoria Cross for his action posthumously. They had run into an entire Japanese battalion. D company #17 and #18 platoons were hit by another Japanese battalion just north of the Gap and were surrounded then overrun with only a few men escaping.

By the morning of the 19th Lawson was facing a situation where A company had just disappeared along with a platoon from D company and two more D company platoons had been wiped out. That left only D company HQ, brigade HQ and the artillery HQ holding the Gap. They were deployed within anti-aircraft shelters with heavy steel doors on both sides of the Gap. One Japanese attack had already been thrown back when Lawson, now surrounded, called for a relief effort to be made. A company of Royal Scots were decimated trying and three Naval platoons met the same fate. A platoon of Grenadiers that had returned after finding out the road junction they were to hold was already occupied also failed to break through. Lawson destroyed all essential records and the telephone switchboard then led the HQ troops out to make a break for it. The HQ was wiped out and Lawson was killed. D company HQ was still fighting though and Captain Bowman led a counterattack which forced the Japanese to withdraw. They stuck back however and Bowman was killed withdrawing back to the shelters.

Maltby at this point ordered a major counterattack by West brigade to halt the Japanese advance, clear the Gap and link up with East brigade. The Punjabs failed to move and the Royal Scots took severe losses. The Grenadier HQ company under Major Hodkinson was told at 2 p.m. to clear the Gap and carry on to Mt.Parker. This despite the fact that Lt. Blackwell had only twenty men left from D company and the flying columns had been wiped out leaving just forty men to attempt the attack. They were joined by a platoon of C company brought up from Aberdeen. Lt. Corrigan and one platoon were to take Mt. Nicholson to cover the flank and they did with only five unwounded men left by the time they took the top of the hill. Despite this they carried on past the hill and fought until midnight when they ran out of ammunition. The rest of Hodkison’s force ambushed around 500 Japanese eating! These troops were dispersed and the carried on the advance. They were joined by remnants of A company of the Royal Scots. Hodkinson and four men flanked the Japanese positions at the Gap and attacked with Lt. Campbell coming in from the south-west and west. They broke through to D company HQ which was down to only seven unwounded men. They called back to battalion HQ and Sutcliffe ordered them to press the attack south to a police station on a knoll covering the entrance to the Gap then onward to Mt. Parker! ” It is difficult to judge which is most incredible, the order given by a Headquarters that obviously did not have the slightest grip on reality, or the little group of men actually undertaking to carry it out.”The station was attacked at 8 p.m. and when they started up the knoll the small force of two officers and twenty-four men met a hail of grenades from the forty or so Japanese defending the position. Hodkinson was killed and most of the force was wiped out. The few survivors under Sergeant Patterson tried to hold off but they were overrun.

A force from East brigade failed to get through the Gap from the south and the Royal Scots were decimated after two attempts. To further deteriorate the situation Col. P. Hennesy, the next succeeding officer in the Canadian ranks was killed by a fluke artillery shell thus leaving the two battalion commanders as the senior surviving Canadian officers.

Morning of the 20th had D co. HQ still holding the Gap, B co. at Pok Fu Lam and C co., less one platoon, at Aberdeen. The other companies had ceased to exist. At noon British Colonel H.B. Rose assumed Lawson’s position of brigade commander. Maltby’s orders to him were much the same as last day; Royal Scots and Grenadiers to clear the Gap and link up with East brigade. B co. split into two columns to circumnavigate Mt. Nicholson and when they got back together on the other side ran into three Japanese companies who took Mt. Nicholson and drove back B co. with twenty-three casualties. By this time the Japanese had lost around 800 men trying to take the Gap.

The next day B co. counterattacked Mt. Nicholson from three sides but were forced to withdraw as of the 98 men engaged they had lost all officers, seven NCOs and 29 men. The Grenadiers were ordered by Sutcliffe to fall back to Mt. Cameron. They were all together now except for C co. at Aberdeen.

Somehow D co. HQ was still holding on despite being under constant fire. At varying times elements of four separate Japanese battalions were arrayed against them. At 4 p.m. they and the rest of the Island were told of a message from Chaing Kai-Shek saying that twenty bombers were en route to hit Japanese airstrips and his ground offensive would begin in ten days. This of course never came about and was purely for morale purposes.

The 22nd saw the final fall of D co. HQ with only twelve unwounded men left ( who attempted to sneak out and were mostly successful ). At 7 a.m. the ammunition had run out, the doors had been blown in by a Japanese light field gun and their commanding officer had been wounded twice. The remaining thirty-seven wounded men surrendered.

Mt. Cameron became the key position for the brigade but it was hit quickly at 8:30 a.m. and the line was breached forcing the Grenadiers to fall back or become surrounded. They withdrew to Wan Chai Gap under intense pressure. C co. under Major Bailie saw the fighting on Mt Cameron and asked brigade HQ if he could assist but he was refused. He moved out any ways and reached Pok Fu Lam en route to Mt. Gough, the brigade’s supposed last stand line. The Japanese brought up two fresh battalions.

On the 23rd the Grenadiers reorganised and moved south to new positions just north of the Aberdeen reservoir and by 3:30 C co. had joined them.

The next day was bright and clear as the Grenadiers began aggressive patrolling to try to fix the Japanese positions. This was required because the Japanese now held all the high ground and this was the only way to figure out where they were now. The Japanese had also brought up the divisional artillery and another fresh battalion.

The Japanese attack at midnight with two companies succeeded in taking Bennett’s Hill after being repulsed once by Major Bailie. Nine hours later the Japanese sent two men through the lines demanding surrender. They were refused by Matlby although a three hour truce went into effect. At noon the attack continued and by three the Winnipeg Grenadiers started to crumble under the pressure and there were no reserves left. On top of this most of the Islands water reservoirs were in Japanese hands and there were only six mobile guns left and only 60 rounds left per gun.

It was due to these factors that at 3:15 Maltby came to the conclusion that further fighting was futile and could risk ” severe retaliation on the large civilian population and could not effect the final outcome” He therefore informed the Governor that the battle was over and ordered all commanding officers to cease fighting and surrender.The Winnipeg Grenadiers kept sporadic firing up until 5 p.m. then destroyed their remaining ammunition and weapons with grenades and moved to Mt. Austin barracks arriving at 7:30 p.m.

There can be no doubt that considering the lack of training the troops of the Winnipeg Grenadiers performed well above the level expected of them. The only unit which attacked more times then they did were the Royal Rifles. They were virtually the only unit fighting for control over the centre of the Island and twice they fought off Japanese battalions with only companies. The unit as a whole only withdrew or broke off attack after sustaining high casualties. They performed with a total lack of transport for movement or resupply, they had no fighting vehicles at all, weak to non-existent intelligence on enemy movements, they were in unfamiliar terrain and led by an HQ that was not at all clear of the tactical situations let alone the strategic one. In all the defense was futile but courageous. Officer casualties were disproportionately high due to them actually leading the attacks from the front. These men would lead ridiculously small forces to counterattack without any covering fire and no artillery support into positions of unknown enemy strength who held the high ground most of the time. The fact that any of these attacks were even successful for a short amount of time is amazing.

From a strategic point of view of course it was all for nothing. The Japanese took Hong Kong much quicker then they had anticipated and depending on which casualty figures you look at the losses to the Japanese of 2 500 to 2 800 men was not crippling. The allies lost around 3 500 defending the Island although the figure is inflated by the Japanese killing of wounded who could not walk.

The whole ‘campaign’ only lasted for seventeen and one-half days and the Canadian contingent which bore the brunt of the fighting were left with only 1 418 survivors after the war from the 1 975 who embarked from Vancouver. In no way could these losses be considered worth the minimal to non-existent gains acquired through the battle for Hong Kong Island.

Last updated on Sep 17, 2006

http://www.wwii.ca/index.php?page=Page&action=showpage&id=45