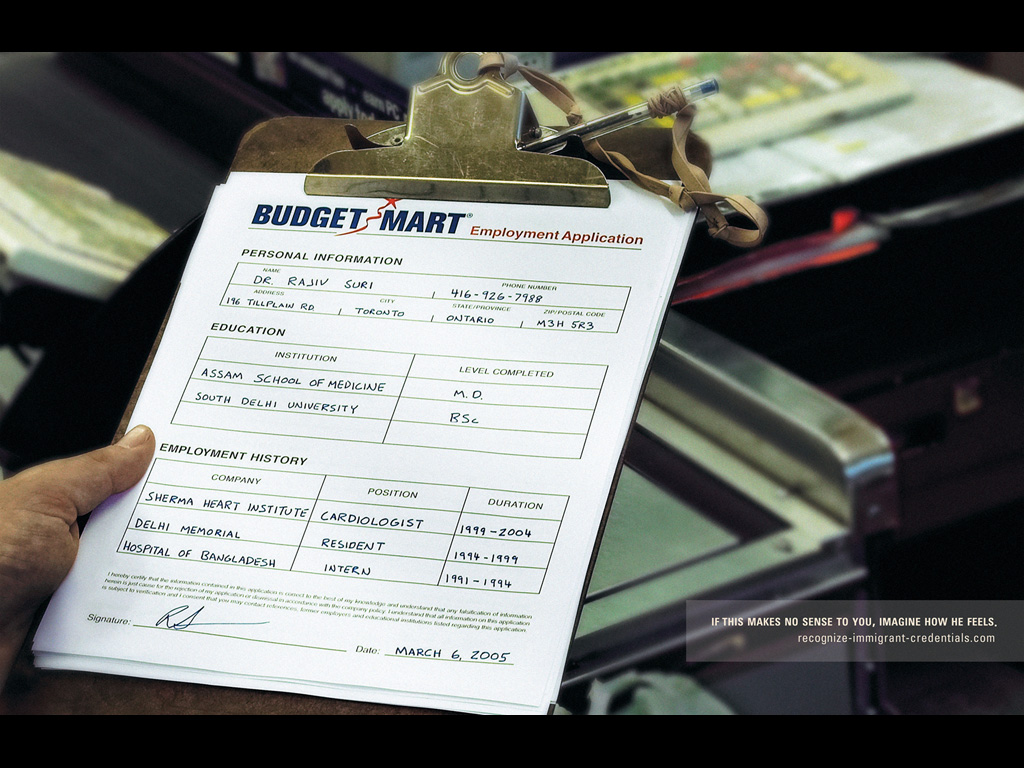

1、印度心脏病专家申请超市工作。(A supermarket job application form, filled out in biro. The applicant: Dr Rajiv Suri, former cardiologist at a heart hospital in India.)

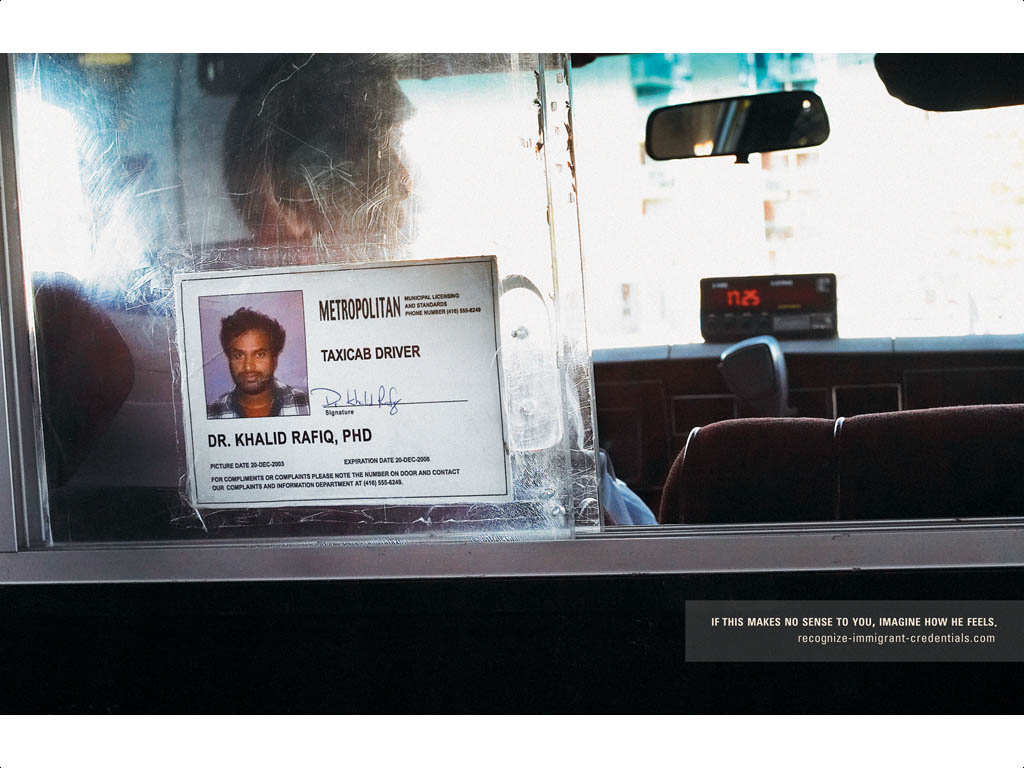

2、加拿大最高学历的出租车司机。(A taxi driver’s photo ID card hanging in the back of a cab. His name: Dr Khalid Rafiq, PhD.)

3、MBA在甜品店打工。(A fast-food worker’s name tag. It reads: Mei Yin, MBA.)

背景搜索:

第一人,网上资料sherma heart institute, assam school of medicine, south delhi university等不匹配。

第二人,网上查到是巴基斯坦旁遮普医学院81年毕业生(Punjab Medical College, Pakistan)

http://www.pmc.edu.pk/doctors1981.htm

第三人,印象中是2004年环球邮报文中的配图,原文如下:

环球邮报:加拿大新移民寻求专业工作困难重重

2004年2月18日21:51:49(京港台时间)

(星星生活专讯)2月18日出版的《环球邮报》在其Career Section刊发文章,介绍新移民寻找专业工作时所遇到的困难,文中提到两位中国大陆移民,一位是有12年工作经验的系统工程师经过相关的培训计划将在Motorola公司实习,另一位是获奖的中国火箭科学家不得不在地铁开咖啡甜点店。文章并引述一位移民律师的评论指出,加拿大政府已经打造出这个漂亮的法拉利(车),但忘记安装引擎。

下面是该篇报道的全文:

Immigrants welcome, roadblocks ahead

Canadian governments are trying to smooth the way for a more diverse work force, but many employers still reject applicants with foreign training despite their credentials, WALLACE IMMEN writes

By WALLACE IMMENWednesday, February 18, 2004 – Page C1

Weiling Qian worked for 12 years in China as a systems engineer responsible for upgrading software in the computers of 1,400 employees of a petrochemical company.

But that time and knowledge became irrelevant when she came to Canada with her husband in 2002. Her path to a new job was blocked by an invisible but formidable barrier well known to newcomers to the country.

“I began to look for a job, but employment agents who saw my resume said I needed Canadian experience,” Ms. Qian said.

For the next few months, she will be wearing a badge identifying her as a member of “Team Motorola” as one of the first interns in the Career Bridge program in Toronto.

It’s one of dozens of new initiatives across the country that are helping foreign-trained doctors get accredited, upgrading skills so pharmacists and nurses can pass their qualifying exams and finding jobs for engineers and other professionals.

In fact, if the mounds of bulky studies and worthy reports issued by programs launched in the past year alone could be used as building material, they could be assembled into a superhighway to jobs for foreign-trained workers.

But even with all the initiatives and a newly formed national consensus that Canada must depend on using the skills of immigrants for future economic growth, potholes and pitfalls continue to abound.

An award-winning Chinese rocket scientist works making cinnamon buns in a Toronto subway station.

Potential employers still routinely ignore resumes from those e with overseas educations.

And even the most successful bridging and training programs are struggling to keep their momentum.

“I call it project-itis,” says Ratna Omidvar, executive director of the Maytree Foundation, a Toronto-based immigrant-assistance organization. “We’ve got a number of really exciting pilots, but the problem is that these are funded for only limited times and in danger of disappearing.”

Most programs to date have placed only a few people at a time in a few professions, while thousands of highly skilled immigrants are still underemployed.

That’s particular the case in non-regulated fields, such as management, finance or journalism, Ms. Omidvar adds.

The problem, experts say, is that there are so many levels and jurisdictions involved, and little communication among them.

“It’s still a multi-jurisdictional nightmare,” says Marie Lemay, chief executive officer of the Canadian Council of Professional Engineers.

“Provinces and agencies are innovating, but ultimately they are working in isolation because none of them have been able to look beyond the small part of the issue in their own jurisdictions.” she says.

“Some days I get overwhelmed by the number of players who all have a role to play,” says Barbara Lawless, sector partnership director of the federal Department of Human Resources and Skills Development, who is in charge of co-ordinating a national approach to assessing and recognizing foreign credentials and experience.

However, the process has to include not only the federal health, industry and immigration departments but also more than 70 departments of the provinces and territories as well as more than 50 regulated professions with at least 400 regulatory bodies.

At least they are all in agreement a national approach is needed, Ms. Lawless says. A report released by her department last winter estimated the future labour supply will fall far short of the demand for educated workers in a growing economy. By 2011, immigration will have to account for all the net growth in Canada’s labour force, according to the report, Knowledge Matters: Skills and Learning for Canadians.

To act on its recommendations, last year’s federal budget allocated $13-million for a two-year effort to improve assessment and recognition of foreign credentials. A task force on medical credentials will report its recommendations at a meeting in Calgary Feb. 29, and other task forces on international nursing and engineering graduates expect to report this spring.

There is a growing awareness that the process has to begin even before immigrants arrive, says Toronto-based immigration lawyer Stephen Green. “The Canadian government has built this beautiful Ferrari, but they forgot to put in the engine.”

Even worse, he says, immigrants are wooed, then abandoned once they get here.

For instance, the Immigrating to Canada as a Skilled Worker website of Citizenship and Immigration Canada promises: “Skilled workers are people whose education and work experience will help them find work and make a home for themselves as permanent residents in Canada.” There is a footnote that some occupations may be restricted “to make sure that Canada does not have too many people with the same skills.” But the site proclaims in bold letters “there are no restricted occupations at this time.”

Such assurances led a British-trained accountant and his bookkeeper wife to sue the federal government, alleging immigration officials in London misled them by assuring them they would be able to use their skills and find jobs here.

Selladurai Premakumaran, who was born in Sri Lanka and is representing himself in the Federal Court of Canada, claimed his dreams have been shattered because the only jobs he has been able to find in Edmonton are shovelling snow in the winter and caretaking in his apartment building.

He estimates there are at least 300,000 unemployed immigrants with professional skills in Canada. “The issue is: If you are recruiting professional people to come to Canada, you should be accepting their credentials and experience. People have to sit down and analyze: Is it worth it to have all this brainpower sitting idle?”

He says he has rejected a recent government offer of a cash settlement to drop the case and plans to continue to trial, which he expects to be scheduled this summer.

In 2002, Canada revamped a system that had tried to match immigration with skills in short supply. Advocates argued that, by the time the workers arrived, the jobs had often been filled and there were shortages in other fields instead.

The current immigration system is not based on specific skills but awards points for education, age, years of job experience and language skills, which is leading to a surplus of foreign-trained job seekers in fields such as engineering.

Ms. Lawless believes the federal task forces will recommend changes in the message given to applicants overseas about the demand for their occupations in Canada. The studies are also expected to recommend on-line tests that candidates for immigration can take to assess their readiness and upgrade their qualifications during the time it takes for them to get officially cleared to come to Canada.

While virtually all skilled immigrants report they come planning to work, a study by Statistics Canada in January found only four out of 10 immigrants find work of any kind within six months of arriving and 21 per cent are part-time.

The “transition penalty,” the time it takes new Canadian immigrants to establish themselves in the work force, is lengthening, according to another study done by the Canadian Labour and Business Centre. It found unemployment rates consistently higher among foreign-born people in Canada for a decade or less. The unemployment rate for Canadians in the country five years or less is 12 per cent versus 7.4 per cent for Canadian-born people in the work force.

Skills are definitely important, with 59 per cent of those entering as “economic class” skilled immigrants finding work versus 39 per cent admitted under the family class and 21 per cent of those admitted as refugees, according to the Statscan report.

Yet, while professions claim to be making efforts to recruit a more diverse work force, many employers still routinely reject job applications from people who have foreign training because they don’t want to take the time to check their credentials, says Timothy Owens, director of World Education Service (WES). In a survey done in 2000 by PricewaterhouseCoopers, 40 per cent of employers reported routinely screening out applicants with foreign degrees. “When we speak with employers, we find this has been a common practice, and one that they did not feel good about. I don’t think it has anything to do with discrimination. Managers said the hiring process is always risky and, if they hadn’t heard of an institution, it was a way of minimizing risk.”

But there has been a lot of change in just the past year, says Mr. Owens, whose not-for-profit group recently expanded into Canada with seed money from the Ontario government. For a fee of $100, paid by the job seeker, WES will search to verify that the degree is authentic, and that the course programs and the school that granted the diploma are the academic equivalents of schools in Canada.

Credentials have not been enough for Ivy Zheng, a guest speaker at a symposium on immigrant skills organized in December by the Canadian Technology Human Resources Board.

Ms. Zheng had been an engineer with the Chinese space program and she won a citation for designing a rocket component that helped launch a Chinese astronaut into space. In the two years since she immigrated to Toronto, though, she has searched in vain for an engineering position and, needing to support herself, she took a job making cinnamon buns in a shop.

“I was so disappointed. I have work experience in my own professional field. I also have other different skills, but I cannot persuade anyone to take me seriously in Canada,” Ms. Zheng says. “I never stop job searching. I spend almost all my spare time on job searching. I know it is my only hope. If give up, I will suffer in labour forever.”

Ms. Qian says she has many friends with impressive skills who have met the same fate, and that is why she is proud to have a cubicle at the modern Toronto Design Centre of Motorola Canada, part of a 200-member group in Markham that designs computer-based communication and safety systems. She explains that computer software design is such a fast-changing field that if you are out of the field for even a short time, “you can become obsolete. If you don’t have a job, you can’t upgrade your skills.”

She was one of almost 2,000 people who applied for 50 intern positions in the Career Bridge program set up last fall by the Toronto Region Immigrant Employment Council and the national non-profit organization Career Edge.

“The response has been overwhelming,” says Career Bridge director Barbara Nowers. While the companies pay the employees’ salaries, Career Bridge does the initial interviews, credential screening and language evaluations before employees choose candidates to get four-month Canadian work experiences. “It’s early days, but Motorola is enthusiastic,” says Agnes van Haeren, the human resources manager for Motorola, which hired Ms. Qian. She reviewed 24 resumes for two available positions and “they were all very impressive.”

“It’s only a four-month commitment,” Ms Nowers adds, “but if the employee does very well, the best result would be that the Career Bridge intern could become a permanent employee.”

The second-best outcome is that the interns come out of the four months with great experience they can put on their resume and have a company such as Bell Canada or Procter & Gamble Co. to vouch for them when they apply for their next job, she adds.

The Ontario government, which provided funding for the pilot project, is so pleased with the results that in January it pledged three years’ support for bridging programs in engineering and technology and an 18-month commitment for a similar program for training teachers.

In addition, the province, which receives almost 60 per cent of all immigration to Canada, pledged $4-million to support skills improvement programs for internationally trained health care workers, pharmacists and technicians.

Growth projections indicate Ontario will need hundreds of thousands of skilled workers in the next decade to replace retiring workers and promote expansion of the economy.

Unfortunately, attitudes of some Canadians don’t seem to be changing as readily as government commitments. Rezaur Rahman, who trained as a computer engineer in Bangladesh and China and finally found a job after having more than 500 resumes rejected, said he was shocked when he attended a recent community meeting in Toronto.

He says one audience member commented that “immigrants are here to do the jobs that local Canadians do not want to do, for example cleaning floors and toilets.

“I could not protest because it is happening — wherever you go, you would find immigrants are cleaning floors, driving taxis or selling in shops no matter what their skills are. If this is the attitude of the local people, I wonder if we are going backwards in history, where all the good jobs and positions were not accessible to non-white people.

“This is ridiculous. Everything we import comes from the countries that train the people immigrating to Canada. It’s a contradiction to say we trust the things they make and not the people who make them.

“We have the skills to be most self-reliant and productive if we are given a chance.”

Would you get in?

Could you qualify to immigrate to Canada as a skilled worker? You might be surprised.

Someone over 50 without an advanced degree and who speaks French “with some difficulty” has a tough time passing the test on the Citizenship and Immigration website designed to help would-be immigrants determine whether they meet the entrance requirements.

The passing grade was raised last fall to 75 points (up from 67) out of a potential 100.

Education can score up to 25 points but to get the maximum,you have to have a masters or PhD degree and at least 17 years of schooling.

Even having two bachelors’ degrees is good for only 22 points, while having completed a trade apprenticeship program or a college degree program is worth 20 points.

You can get up to 21 additional points for four or more years of work experience in a skilled profession, but you get fewer points for less experience and no points if you’ve spent less than one year on a job in your field.

Language skills can be worth as many as 24 points, with a maximum of 16 awarded for high proficiency in English (or French) as a first language and another eight points for having high proficiency in French (or English) as a second language but only two for basic comprehension.

Next comes the age barrier. If you are between 21 and 49, you get 10 points. If you are younger or between 50 and 53, you’ll get only a few points.

And past age 53, you get no points at all.Having prearranged employment is worth 10 points.A final 10 points is possible for family factors. Try your luck at:

www.gc.ca/english/index.html.

Helpful websites

An extensive list and links to employment and education programs for immigrants across the country is updated regularly on the non-profit Maytree Foundation website, http://www.maytree.com.

Association of International Physicians and Surgeons is a non-profit organization advocating for recognition of foreign-trained doctors, http://www.aipso.ca.

Bridging programs for internationally trained teachers, engineering technicians, pharmacists, health professionals and laboratory technicians that are sponsored by the province of Ontario are all described on the website http://www.edu.gov.on.ca.

B.C. Internationally Trained Professionals Network is creating associations of doctors and engineers to advocate with government and regulatory agencies, http://www.bcitp.net.

Canadian Information Centre for International Credentials is a site supported by provincial education ministries, provides links to education, professions and trades and financial assistance programs, http://www.cicic.ca.

Career Bridge, a Toronto-based internship program that gives skilled immigrants Canadian experience, http://www.careeredge.ca.

Creating Access to Regulated Employment for Nurses program for skills upgrading and preparation for licensing, http://www.care4nurses.org.

Internationally Educated Professionals, sponsored by the City of Toronto, organizes free conferences with presentations and advice for foreign-trained teachers, accountants, nurses, engineers and technicians. This Friday, Feb. 20, their Breaking Barriers Building Bridges conference is at the Toronto Congress Centre. Details are on the website http://www.pcpi.ca{tilde}iep/.

Medical Licensure Program of Manitoba Health, provides skills assessment and assistance in Manitoba, http://www.gov.mb.ca/health/mlpimg.

Pathways program of the Ontario Society of Professional engineers is currently closed to new applications pending review, http://www.careercentre.ospe.on.ca.

Skills for Change, programs for upgrading and certification of internationally trained electricians, millwrights and construction trades, http://www.skillsforchange.org.

World Education Services, provides helpful evaluation of educational credentials for licensing and further education. http://www.wes.org/ca.