来源:知社学术圈

基因编辑婴儿在中国诞生的消息一经发布,举世哗然,贺建奎成众矢之的,被群起攻之。不过也有一位声名显赫的学者站出来,为他说话。

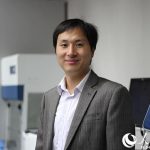

他是George Church,哈佛大学教授,美国国家科学院院士,美国国家工程院院士。Church教授发展了第一个基因测序的方法,联合发起了人类基因组工程,联合发起了美国脑科学工程(BRAIN Initiative),被维基百科誉为合成生物学之父,同时也是CRISPR基因编辑技术先驱之一。美东时间11月28日,在Science发表的关于贺建奎基因编辑婴儿的专访中,Church教授称:

I feel an obligation to be balanced

知社为您编译专访全文如下,与您分享。仅客观反映各方视角,不代表知社立场。因水平有限,编译难免存在偏差,因此文末附英文全文供您参考。

Q:您如何看待贺所面临的广泛批评?

A:我实在不应该将自己和一个我所知不多的人绑在一起,但我觉得自已有义务保持公正。其他的人是如此的极端,而我居于中间,倒显得我是他的同党。在我看来,整个事件就像一场欺凌。我所听到的最严重的事,是他手续欠缺不全。他显然不是第一个手续有问题的人,只是这事的筹码更高而已。如果实验效果不佳导致有人受到伤害,也许这样的攻击有点道理,比如1999年死于基因疗法的Jesse Gelsinger。但这究竟是Jesse Gelsinger亦或是第一个体外受精的试管婴儿Louise Brown呢?这是问题之所在。

Q:您认为这个实验违背伦理么?

A:有人说生殖细胞的编辑国际上现在有一个冻结令,而我参与了那个呼吁暂停生殖细胞编辑的研究报告。但冻结和暂停并非永久禁止。那里面给出了一个注意事项清单需要恪守。看起来他按照美国国家科学院发布的这个清单照做了,而且加了几项他自己的。要知道总有一个时间节点,我们不得不说,我们已经做了几百个动物实验和很有一些人类胚胎实验。也许必须等待尘埃落定之后才会知道,存在着镶嵌和脱靶现象,会带来医疗后果。这样的现象也许永远不会是零。要知道,我们并不会等到辐射为零时才开始做PET扫描或者X光检验。

Q:您什么时候知道这项研究的,当时是如何反应?

A:大概一周以前。我当时希望他正确地实施每一个步骤。一个人能够尝试的机会不多的。他没有采用我也许会采用的方式,但我希望实验后果不会太糟糕。只要最后是正常健康的孩子,我们的领域和这个家庭都会没事的。

Q:您如何看待他决定抑制一个基因以防止艾滋感染?

A:在我看来CCR5是一个大胆的选择。在一定程度上这不合情理,但从另一个角度看其实比针对地中海贫血和镰刀型红血球病更合逻辑。这两种疾病是许多CRISPR研究者的目标,但都可以通过胚胎著床前基因诊断予以预防。真正的问题是,什么才是最好的第一个案例呢?

Q:但中国女性艾滋感染率相对较低。这并不像比如说南非的夸祖鲁-纳塔尔省,保护年轻女性免于艾滋感染的医疗需求非常迫切。

A:毋容置疑,这里的医疗需求被夸大。也许有一些小的风险。项目的主要驱动力显然是测试CRISPR。

Q:您如何看待关于实验并不针对没有得到满足的医疗需求的批评?

A:在这里,没有得到满足的医疗需求是迄今没有治愈艾滋的疗法和预防艾滋的疫苗。从这一点来看,这个医疗需求比地中海贫血更大。除非父母双方都是纯合子,对地中海贫血有其他的办法。

Q:那关于CRISPR可能脱靶的担忧呢?

A:我不会说一定不会有脱靶的问题。但让我们做出指控前先做一些定量的分析。脱靶也许会被观测到,但未必是临床的。没有证据显示脱靶给动物或者细胞带来问题。我们一些猪有十几个CRISPR突变,有一种老鼠40多个CRISPR点经常脱靶。但我们还没有看到负面后果的证据。

Q:您会参与这个实验吗?

A:也许不会。但我也不会将1918流感病毒或者天花病毒传播给大众。这个实验比将病毒传染给大众风险略低。

Q:也有人担心对贺实验的反弹会损害这个领域?

A:在基因疗法发展的早期,前期的初步研究比现在要少很多,而且有三例死亡事件,阻滞了那个领域的发展。这也许使得我们更加小心谨慎,基因疗法如今也卷土重来欣欣向荣。我不认为这两个基因编辑的孩子现在会面临死亡的威胁。

Q:那关于贺不够透明的指控呢?在植入基因编辑胚胎之前,他应该发表前期初步结果,并将自己的意图公之于众。

A:这是合理的批评,他也将为此付出代价。我自己显然是在光谱的另一端,极端透明。

‘I feel an obligation to be balanced.’ Noted biologist comes to defense of gene editing babies

By Jon Cohen Nov. 28, 2018 , 2:50 PM

When a researcher in China startled the world earlier this week with the revelation that he had created the first gene-edited babies, only one prominent scientist quickly spoke out in his defense: geneticist George Church, whose Harvard University lab played a pioneering role in developing CRISPR, the genome editor used to engineer embryonic cells in the hugely controversial experiment. Church has reservations about the actions of He Jiankui, the scientist in Shenzhen, China, who led the work.

The fiercely debated experiment, described by He at a meeting in Hong Kong, China, today, used CRISPR to try to make the babies resistant to HIV by crippling a receptor, CCR5, that the virus uses to infect white blood cells. But Church also thinks there’s a frenzy of criticism surrounding He that exaggerates the severity of what one critic gingerly called his “missteps” but another called “monstrous.”

ScienceInsider spoke with Church shortly before He’s lecture in Hong Kong, but Church had seen the data earlier. This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Q: What do you think of the criticism being heaped on He?

A: I’d just as well not hang myself out to dry with someone I barely know, but I feel an obligation to be balanced about it. I’m sitting in the middle and everyone else is so extreme that it makes me look like his buddy. He’s just an acquaintance. But it seems like a bullying situation to me. The most serious thing I’ve heard is that he didn’t do the paperwork right. He wouldn’t be the first person who got the paperwork wrong. It’s just that the stakes are higher. If it had gone south and someone had been damaged, maybe there would be some point. Like what happened with Jesse Gelsinger [who died in a 1999 gene therapy experiment]. But is this a Jesse Gelsinger or a Louise Brown [the first baby born through in vitro fertilization] event? That’s probably what it boils down to.

Q: Do you think the experiment is unethical?

A: People have said there’s a moratorium on germline editing and I contributed to reports that called for that, but a moratorium is not a permanent ban forever. It’s a checklist of what you have to do. It really seems like he was checking off the published list [see p. 132] by the National Academy of Sciences and added a few things of his own. At some point, we have to say we’ve done hundreds of animal studies and we’ve done quite a few human embryo studies. It may be after the dust settles there’s mosaicism and off targets that affect medical outcomes. It may never be zero. We don’t wait for radiation to be zero before we do [positron emission tomography] scans or x-rays.

Q: When did you learn about it and what was your reaction?

A: About a week ago, and I was hoping he did everything right. You don’t have that many shots on goal. He’s not doing it the way I’d do it, but I’m hoping it doesn’t work out badly. As long as these are normal, healthy kids it’s going to be fine for the field and the family.

Q: What do you think of his decision to cripple a gene to prevent HIV infection?

A: It struck me as bold choice to do CCR5. In some ways it doesn’t make sense, but in another way it makes more sense than β-thalassemia or sickle cell, both of which you can prevent with preimplantation genetic diagnosis. [These genetic diseases are two prime targets of many CRISPR researchers.] The real issue is what’s the best first case.

Q: But there’s a relatively low rate of HIV infection in Chinese women. This isn’t like in, say, KwaZulu Natal in South Africa, where the medical need to protect young women from the virus is great.

A: This was a stretch, there’s no doubt about it. There could be a bunch of small risks. Quite clearly the major motivator was testing CRISPR.

Q: What do you think of the criticism the experiment doesn’t address an “unmet medical need”?

A: The unmet medical need is there is no cure or vaccine for HIV. And in that sense, there’s more of a medical need than there is for β-thalassemia, for which there is an alternative, unless both parents are homozygous. [If both parents have two copies of the mutant gene, all of their offspring will develop the disease.]

Q: What about concerns that CRISPR will make unintended edits in the genome, so-called off-target effects?

A: I’m not saying they’ll never be an off-target problem. But let’s be quantitative before we start being accusatory. It might be detectable but not clinical. There’s no evidence of off-target causing problems in animals or cells. We have pigs that have dozens of CRISPR mutations and a mouse strain that has 40 CRISPR sites going off constantly and there are off-target effects in these animals, but we have no evidence of negative consequences.

Q: Would you have been part of this experiment?

A: Probably not. But I probably wouldn’t have put the sequence of the 1918 flu virus or smallpox virus in the public domain. This is a slightly lower risk than putting potent pathogenic sequences in the public domain.

Q: There’s some worry that the backlash to He’s experiment will harm the field.

A: In the early days of gene therapies when there were far fewer preliminary studies, there were three deaths that set back the field. It may have just made us more cautious. And gene therapy is certainly back in force. And I don’t think these kids [the babies whose genomes He edited] are going to die.

Q: What about the argument that He wasn’t transparent enough and should have published preliminary work and done more to make his intentions clear to the scientific community before implanting the embryos?

A: Those are valid critiques, and he probably will pay some price. I’m a little extreme on the transparency end of the spectrum [Church’s website lists more than 100 affiliations he has with funders, companies, and nonprofits], and it’s nice to have company on that. But at some point, we should start focusing on the health of the babies.