多维社记者陈湘编译报导/在几内亚首都克纳克里,这个摇摇欲坠的城市的边缘,在烈日之下,中国和几内亚工人正肩并肩地在建筑工地上忙碌,这是一个两国关系的最新的象征,一种悠久和经久不衰的联盟:一座造价5000万美元,有5万个座位的体育场。

这个城市充满了这种友谊的标志,早在20世纪50年代末,当几内亚被孤立并力图走社会主义道路时,中国就与几内亚发展了友好关系。

在烈日之下,中国和几内亚工人正肩并肩地在5万个座位、投资5000万美元的体育馆建筑工地上忙碌,这是一个两国关系的最新的象征,一种历史悠久和历久不衰的联盟(资料图片)

但到目前为止,几内亚还没有从全球增长最快的市场得到自己真想要的东西:价值数十亿美元的协议,以建设本国急需的基础设施。几内亚想得到这些东西的交换条件,就是让外国可以参与开采他们这个穷国的庞大资源储备,主要是铝土矿和铁矿。

这是纽约时报刊登的记者莉迪娅·博格林(Lydia Polgreen)在一篇题为“中国在非洲的投资下降,希望下沉”(As Chinese Investment in Africa Drops, Hope Sinks)的报导所述。报导说,随着全球商品价格暴跌和中国的几个非洲伙伴们更深地陷入到了混乱中,中国已放弃了一些危险的和最激进的计划,而寻找有保值保证的投资,而这也是西公司长期以来都在为他们的投资所寻找的:经济和政治稳定。

“这里的政治局势不太稳定,国际市场也不很有利。””中国驻几内亚大使火正德在接受采访时解释中国对在几内亚大举投资的踌躇时说,中国已经毫不犹豫地在几内亚投资了数十亿美元,几内亚军政府在长期掌权的总统于08年12月去世后,掌控了政权,但是军政府并没有被国际社会所接受。

在几内亚一处建筑工地上,一位中国监工在监督工程的进行(资料图片)

就在一年前,随着国际市场对铜,锡,石油和木材的需求被推升到一个新的高度,中国似乎颠覆了在非洲几十年的旧秩序,踏入了西方大公司留下的大量的投资空白,西方这些公司胆子太小,他们不敢投资于非洲大陆的资源丰富但社会秩序脆弱的国家。在这轮对非洲的财富待新的争夺中,中国正在寻求一个大的份额。

中国没有任何附带条件,而且有着强烈的风险承受意愿,中国似乎是向非洲提供了一个完整的经济和政治的替代援助方案,他们可以替代西方国家和国际援助机构压非洲国家接受的条件苛刻的援助和经济结构调整方案,但是高速增长中的中国为寻求伙伴与资源似乎正开出空白支票。

纽约时报的报导说,如今,中国对非洲资源产品的需求停滞不前了。中国的国有企业正在从局势更稳定的赞比亚和利比里亚等国,逢低买进铜和铁矿石等。但是,中国公司现在拼命压价,同时他们也避免到一些最混乱的角落大陆去。面临财政收入下降的非洲各国政府正在意识到,毕竟他们可能还仍然需要西方的帮助。

“最近我们已经看到中国公司雄心勃勃地进入到一些没有人愿去的国家,这种情况可能会改变。”一家叫欧亚集团的私营研究机构分析师菲利普·德蓬戴(Philippe de Pontet)分析说。

近年来中国似乎颠覆了在非洲几十年的旧秩序,踏入了西方大公司留下的大量的投资空白,(资料图片)

中国在2007年宣布了一项与刚果达成的90亿美元的交易,中国通过在刚果建设公路,学校,水坝和铁路,帮助这个面积相当于西欧、经历了十多年战乱的国家进行重建工程,来换取该国巨大资源宝库中的铜,钴,锡,金等矿藏资源。据英国《观察家报》的报导,根据这项交易中国政府协助刚果建设2400英里道路、2000英里铁路、32所医院、145间健康中心和2所大学;刚果政府以1000万吨的铜和40万吨的钴作为回报。

但是现在这笔交易受到了人们的质疑,因为资源价格的下降,已经使得刚果在谈判中处于一种更为不利的谈判地位。刚果也突然发现,她自己需要国际货币基金组织的帮助,但是国际货币基金组织反对而该组织拒绝对刚果的旧债一笔勾销刚果的旧债务,尽管刚果与中国达成了一项新的用矿产交换的贷款协议。刚果的政治和种族动乱仍然严重,其经济已经接近崩溃。

如果是一年前,这些因素对中国来说似乎都是无关紧要的。中国似乎不在乎这些局势的影响:中国继续在海盗出没的索马里海域寻找石油,或者在像津巴布韦这样的地方开采金属矿产,中国公司都没有退缩,照样做生意。

不像许多西方公司那样,中国国有石油公司已经毫无顾忌与因为达尔富尔的冲突而成为一个国际唾弃的苏丹政府做生意。

纽约时报报导指出,中国倡导在非洲投资的一种新模式:主权国家之间的贸易互利与互不干涉,而这种干涉本来对来自西方国家的捐助者和投资者而言,是常事,他们的捐助和投资往往带有劳工和环境标准的要求,以及尊重民主和人权的要求。

事实证明这些政策深受非洲各国政府的欢迎,中国和非洲之间的贸易,从20世纪80年代不到1000万美元的增长到到2008年的1000多亿美元。非洲领导人以公开提到中国资金和投资替代了如国际货币基金组织和世界银行这样的西方国家占主导地位的机构的作用。

但是在几内亚,这个有着世界上最大的铝土矿矿床的国家,指望中国开采矿土铝的一个希望已经几乎破灭。

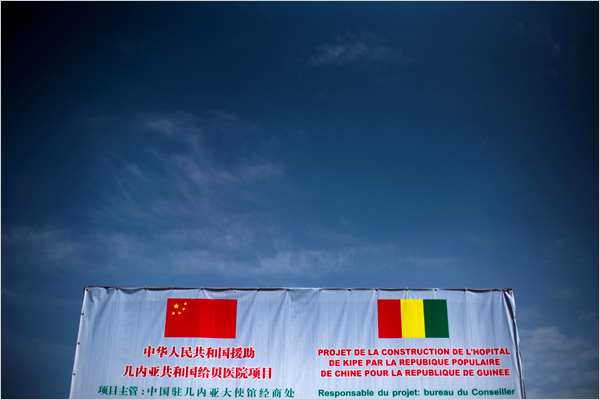

中国在几内亚建设的一个医院工地上,用中文和法文写的标志(资料图片)

“中国人已经改变了他们的策略,”几内亚财政部和赞成中国投资的高级经济师易索利·迪亚洛(Sory Diallo)说。“他们不会将50亿美元注入到一个市场环境不明朗的不稳定的国家。”

法国殖民者曾经将几内亚称为“地质奇迹”,有着如此丰富的贵金属矿藏。尽管开采多年,每年有几十亿美元的利润,但是几内亚仍然是非洲最贫穷和最不发达的国家。

所以毫不奇怪的是,在统治几内亚达24年的强人兰萨纳-孔戴(Lansana Conté)2008年去世后,在军政府取得政权后,几内亚政府希望利用中国的现金和建设经验来发展几内亚经济。

纽约时报的报导说,中国确保获得在非洲的矿藏的做法,就是签订以帮助建设大型项目的方式换取矿物的协议。在安哥拉,这样的安排能够保证中国获得非洲第四大石油生产国的石油,安哥拉在恶性的内战持续了几十年、支离破碎后,目前走上了蓬勃发展的路程。

中国和安哥拉官员吹嘘这种伙伴关系是中国在非洲大陆投资的的典范,这是让这两个国家都受益的的一种双赢游戏。

但是,这一说法,在经济衰退之际已被证明是有问题的。非洲各国政府现在认识到,这些贷款在本质上,是预支本国未来的收入,而原料价格下跌可能使他们背负堆积如山的债务。

在刚果,这样的事情似乎正在发生。按目前价格计算,要满足与中国达成的交易中的严格的生产指标,刚果必须做出很大努力,英国非营利组织“发展权利与义务”(Rights and Accountability in Development)执行总监帕特里夏·菲尼(Patricia Feeney)说。

“刚果民主共和国对可以依赖中国人抱有太大期望,他们以为已经可以不理会西方的捐助者。在这个过程中,他们可能在设法疏远那些愿意提供帮助的人,”菲尼女士说。

中国帮助建设的项目工地上的非洲民工(资料图片)

在几内亚,中国已经退出了一座急需10亿美元的水电大坝的建设,本来,几内亚官员曾经将中国对这座水坝的援建视为木已成舟的事情。

“这个大坝不是一个礼物,它是一种投资,”中国驻几内亚大使火正德解释说,“这样的方式才能达到双赢。”

纽约时报的报导指出,几内亚人开始对中国的投资越来越持怀疑态度。许多人觉得中国的公司像西方的公司一样,都是剥削性的,即使不比西方更残酷,至少也是一样厉害。几内亚的军政府在12月上台后,就突击搜查连涉嫌出售假药的中国公司,但是空袭搜查却演变成了对中国企业的公开掠夺,是在发泄一种长期受到压制的怨恨。

哈米杜·孔德(Hamidou Condé)敞开着衣服,在烈日下挖地基,这是一个由中国公司承建的新医院工程,也是中国和几内亚友谊的又一象征。

35岁的孔德先生有两个妻子和四个孩子,他说,他在用各种工具,包括在岩石铲,鹤嘴锄和斧头,挖坚硬的岩石,已经干了两个月,但是还没有从中国人的工头那里拿到一分钱工资。

“我们像奴隶一样干活,”孔德先生说,“然后像奴隶一样没有报酬。中国没有给几内亚带来什么好处。”

As Chinese Investment in Africa Drops, Hope Sinks

By LYDIA POLGREEN

Published: March 25, 2009

CONAKRY, Guinea — Chinese and Guinean workers toil shoulder to shoulder on a sun-blasted construction site at this crumbling city’s edge, building the latest symbol of an old and sturdy alliance: a $50 million, 50,000-seat stadium.

This city is littered with such tokens of a friendship that first flowered when Guinea was an isolated and struggling socialist state in the late 1950s.

But so far Guinea has not gotten what it really wants from the world’s fastest growing economy: a multibillion-dollar deal to build desperately needed infrastructure in exchange for access to the impoverished nation’s vast reserves of bauxite and iron ore.

As global commodity prices have plummeted and several of China’s African partners have stumbled deeper into chaos, China has backed away from some of its riskiest and most aggressive plans, looking for the same guarantees that Western companies have long sought for their investments: economic and political stability.

“The political situation is not very stable,” Huo Zhengde, the Chinese ambassador here, said in an interview, explaining the country’s hesitation to invest billions in Guinea, where a junta seized power after the death of the longtime president in December. “The international markets are not favorable.”

Just a year ago China appeared to be upending the decades-old order in Africa, stepping into the void left by large Western companies too timid to invest in the continent’s resource-rich but fragile states as the market for copper, tin, oil and timber soared to new heights. In the new scramble for Africa’s riches, China sought a hefty share.

With a no-strings-attached approach and a strong appetite for risk, China seemed to offer Africa a complete economic and political alternative to the heavily conditioned aid and economic restructuring that Western countries and international aid agencies pressed on Africa for years, often with uninspiring consequences. Rising China, seeking friends and resources, seemed to be issuing blank checks.

Today, China’s quest for commodities has not stalled. State-owned companies are bargain-hunting for copper and iron ore in more stable places like Zambia and Liberia. But Chinese companies are now driving harder bargains and avoiding some of the most chaotic corners of the continent. African governments facing falling revenues are realizing that they may still need the West’s help after all.

“We have seen in the recent past Chinese companies wade into countries nobody else would,” said Philippe de Pontet, an analyst at the Eurasia Group, a private research firm. “That may be changing.”

In 2007 China announced a $9 billion deal with Congo for access to its giant trove of copper, cobalt, tin and gold in exchange for developing roads, schools, dams and railways needed to rebuild a country roughly the size of Western Europe and shattered by more than a decade of war.

But that deal is now in doubt as falling prices have left Congo in a much weaker negotiating position. It also suddenly finds itself needing the help of the International Monetary Fund, which has objected to writing off the country’s old debt even as Congo takes on what amounts to new mineral-backed loans from China. Congo’s political and ethnic turmoil remains deep, and its economy is near collapse.

A year ago those factors seemed irrelevant. Chinese companies did not flinch from making deals to search for oil in the pirate-infested waters off Somalia, or to mine industrial metals in places like Zimbabwe.

Unlike many Western companies, Chinese state oil companies had no qualms about doing business with the government of Sudan, which has become an international pariah because of the conflict in Darfur.

China espoused a new model for African investment: mutually beneficial trade between sovereign nations with none of the meddling so common among Western donors and investors, with their demands for labor and environmental standards, as well as respect for democracy and human rights.

These policies proved popular among African governments, and trade between Africa and China grew to more than $100 billion by 2008, from less than $10 million in the 1980s. African leaders spoke openly about China’s offer of an alternative to the edicts of Western-dominated institutions like the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

But here in Guinea, which has some of the world’s largest deposits of bauxite, an ore needed for making aluminum, that hope has all but collapsed.

“The Chinese have changed their strategy,” said Ibrahima Sory Diallo, a senior economist in Guinea’s Ministry of Finance and an advocate for Chinese investment. “They are not going to inject $5 billion into an unstable country in an uncertain market climate.”

French colonists once called Guinea a geological scandal, so rich are its deposits of valuable minerals. Despite years of mining and billions in profits, Guinea remains one of the poorest and least developed countries in Africa.

So it is no surprise that Guinea’s government, first under Lansana Conté, the strongman who ruled for 24 years until his death last year, and the junta that replaced him, wanted to tap China’s cash and building expertise.

China’s approach to securing minerals in Africa has been to sign agreements to build huge projects in exchange for minerals. In Angola, this kind of arrangement has guaranteed Chinese access to oil in Africa’s fourth largest oil producer, which is now booming after emerging tattered and broke from a vicious civil war that lasted decades. Chinese and Angolan officials trumpeted this partnership as a model for Chinese investment in the continent, a win-win relationship benefiting both countries.

But that formulation has proved problematic in an economic downturn. African governments are now realizing that these deals are in essence loans against future revenue, and falling prices could leave them saddled with giant piles of debt.

That is what appears to have happened in Congo. At current prices Congo would struggle to meet the stringent production targets in the Chinese deal, said Patricia Feeney, executive director of Rights and Accountability in Development, a Britain-based advocacy group.

“The Congolese have raised expectations so much that they could rely on Chinese and turn their backs on Western donors, and in the process they have probably managed to alienate people who were willing to help,” Ms. Feeney said.

In Guinea, China has backed away from what Guinean officials portrayed as a done deal to build a much-needed $1 billion hydroelectric dam.

“The dam is not a gift; it is an investment,” said Mr. Huo, the Chinese ambassador. “That is what win-win means.”

Guineans are increasingly suspicious of Chinese investment. Many people see Chinese companies as being just as exploitative as Western ones, if not more so. After the military took power in December, it raided Chinese companies suspected of selling fake medicines, but the raids degenerated into open looting of Chinese businesses, tapping a vein of resentment long suppressed.

Hamidou Condé works bare-chested under the relentless sun, digging a hole for the foundation of a new hospital being built by a Chinese company, yet another symbol of Chinese-Guinean friendship.

Mr. Condé, 35, who has two wives and four children, said that he had been digging in the hard rock with a shovel, pick and ax for two months, but that he had yet to receive any pay from his Chinese taskmasters.

“We work like slaves,” Mr. Condé said. “And like slaves we are not paid. The Chinese bring nothing good to Guinea.”