CBC/今天是中越1979年战争30周年纪念日。中国政府没有对此发表评论,媒体也没有对纪念日进行报道。中国官员只是表示中国愿意和越南保持友谊。

中国军队在1979年2月17日攻入越南,并把这场战争称为对越自卫还击战。中越边界冲突在80年代的大部分时间里一直进行。

有报道说,中国对越南发起进攻是为了惩罚越南在1978年12月侵入柬普寨,使中国支持的红色高棉下台。

对这场中越战争中国没有公布很多资料,学校里也不能研究这个课题。

中国评论﹕中越心结不比中日少

明报孙嘉业/昨天是1979年中国教训越南的「自卫反击战」开战30周年的纪念日。在内地,昨日的官方媒体可谓无声无息,在广西边境的解放军烈士墓园,也不见有官式的拜祭活动;倒是互联网上关于30年前那场战争的议论颇多,显示内地民众对那场战争的一些反思。

中越开战30周年

已故领导人邓小平当时执意要打这一仗,有两个目的,一是为了挽救被推翻的赤柬政权,在柬埔寨国内正在公审赤柬头目的今天来说,这一点名既不正,言亦不顺;第二个目的是为了向美国表示友好,替友邦报当年一箭之仇,这一点虽无明说,但中美1月1日甫建交,邓小平于1月28日至2月5日访美期间已向美方通报惩越之事,回国后不足两周就挥军入越,从这一时间表似也略知一二,而中国惩越之战,苏联备受煎熬,美国当然乐观其成。内地一种说法是,中国要搞好和美国的关系,对越一战也是非打不可。

虽然中方于79年3月5日就宣布从越南撤军,但中越边界的战火,一直持续了五、六年之久,解放军当时以全国各大军区抽调部队轮番上阵实行「骑线拔点」,即在边境不断袭击越北,牵制越军主力。战事之惨烈较惩越之战不遑多让,港人熟悉的歌曲《血染的风采》原来就是一首讴歌边防战士的歌。

两国关系多谈互惠

今天的中越关系,已经被定位为好邻居、好朋友、好同志、好伙伴的「四好」关系,与过去的「同志加兄弟」定位相较,少了意识型态的热情,却多了实用的互惠内容,河内对中国的地区大国地位已经默认,北京对越南这一难得的同门师弟也较为珍视。但只要看看中越边境两边如林的墓碑,看看两国充满争端的南海地图,就明白中越之间的历史心结并不比中日之间少。

法新社: In China, war with Vietnam is forgotten history

by D’Arcy Doran D’arcy Doran – Mon Feb 16, 9:22 pm ET

SHANGHAI (AFP) – China invaded Vietnam 30 years ago this week, but the event will not be officially marked by Beijing, which refuses to acknowledge the war — making life even harder for veterans who are haunted by it.

After a year surrounded by death in Vietnam — gripping a machine gun between diving for cover from howitzer fire — Zhou Feng decided to spend the rest of his days protecting life, not ending it.

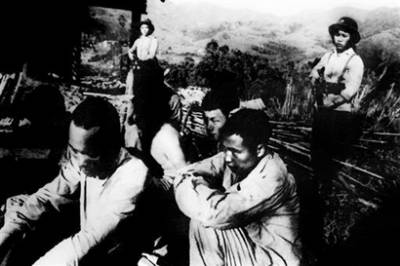

(Chinese soldiers arrested are kept by Vietnamese fighters on the battlefield of Cao Bang, in February 1979. China invaded Vietnam 30 years ago this week, but the event will not be officially marked by Beijing, which refuses to acknowledge the war — making life even harder for veterans who are haunted by it. AFP/File )

The former infantryman said the shame he felt at all the death pushed him to study animal medicine when he returned from the front.

Zhou, 45, now works at a veterinary clinic and at home he shelters 30 stray dogs — by coincidence one for each year since the war.

“In China, the government respects history about as much as they respect these dogs,” Zhou said.

Chinese academics are prohibited from studying the war, in part to avoid damaging relations with former foe Vietnam, said Xiaoming Zhang, an associate professor at the US military’s Air War College in Alabama.

Zhang is writing a book about the conflict that he hopes will be the closest thing to a Chinese account of what happened.

“It was Deng Xiaoping’s war,” Zhang said, adding study of the bloody and inconclusive war may also be banned to prevent it from becoming a “black stain” on the record of the father of China’s economic reform.

China attacked Vietnam, according to non-Chinese accounts, to punish it for invading Cambodia in December 1978 and bringing down genocidal tyrant Pol Pot and his Beijing-backed Khmer Rouge communist regime.

Bad blood with the Soviet Union and Moscow’s support for Hanoi, which Beijing saw as increasingly aggressive after beating the United States and South Vietnam, was also an important factor.

“(Deng) used the war against Vietnam to convince the US that China was a reliable ally for countering Soviet expansion,” Zhang said.

Despite China declaring victory after a month of fighting, a low-intensity conflict smouldered for most of the 1980s.

“It was a bleeding strategy to burden Vietnam while China was able to carry out economic reforms,” Zhang said.

Like Zhou, Xu Ke fought on the frontlines in 1984 as part of that bleeding.

He later spent two years researching a memoir about the war, but found library after library had nothing about the conflict and even army historians turned him away.

“History is just like a wall, made up of different bricks,” Xu said. “But the brick that should contain our history has been deliberately removed. That’s why I wrote the book, I wanted to put it back.”

The 44-year-old finished the book about five years ago, but has since given up finding a publisher to take it.

There are no figures for how many died in the extended conflict, but losses were massive. Non-Chinese scholars estimate for the first month alone 25,000 to 63,000 Chinese were killed and 20,000 to 62,000 Vietnamese died, said historian Peter Worthing, author of “A Military History of Modern China”.

“Clearly the 1979 war served as a warning or wake-up call to the Chinese leadership that the PLA needed improvement,” Worthing said, referring to the People’s Liberation Army.

Despite its advantage in numbers and strength, China fought to a bloody stalemate and had no effect on Vietnam’s foreign policy, he said.

The Chinese government “saw little to boast about and this undoubtedly helps explain the lack of official acknowledgement of this war and those who fought in it,” Worthing said.

Wu, a former propaganda officer who served in Vietnam 25 years ago, said he used to leaf through his teenage son’s history textbooks, searching in vain for a mention of the war.

“Why should this war be hidden from history? It’s so unfair to us,” he said, asking to be identified by his surname only because of the topic’s sensitivity.

The 45-year-old has recurring nightmares about being shelled, but has never spoken to his son about his experiences.

“How could he understand our time and the war?” Wu asked. “He would feel like he was hearing someone else’s story even though it would be coming from me.”

中越战争三十周年再访香港专家杨达

德国之声/1979年2月17日,中国军队动用20万兵力攻入越南北部边境,开始了中越战争。在双方都付出重大人员伤亡的代价后,中国在1个月内撤出了越南。时隔30年,国际政治格局发生重大改变,中国与越南这两个迄今仍然挂着社会主义标签的邻邦也在继续致力于克服障碍,发展友好的双边关系。中越战争25周年时德国之声曾发表对香港浸会大学新闻系越南问题专家杨达的采访,引起广泛反响。中越战争30周年之际,杨达再度接受了德国之声的专访。

德国之声:中越战争已经过去30年,您觉得两国的邦交能否成为一种很正常很友好的邦交呢?因为两国现在仍然存在南海等争端。

杨达:争端还是有一些,主要是你刚才说的南海那方面,可是大体来说,中越关系还是不错的。为什么?因为我们现在已经进入”后冷战时期”,过去困扰中越关系的问题,比如苏联的因素等等已经不存在了。所以一般来说,我觉得中越关系还是不错的。除了在战略关系以外,还有就是经济,贸易方面的问题。尤其是中国与东南亚国家,尤其是东盟已经建立所谓自由贸易协定。这很重要。因为中国在所谓的”软力量”方面在东南亚的影响主要是正面的,所以从现在来说,相比30年前的世界来说,中越关系还是不错的。

德国之声:我们也注意到,这么多年来,越南都在效仿中国实行经济方面的改革,在体制上还是保持一种缓慢的发展态势。从这个角度看,中越两国会不会在体制的改革上也产生一些互动作用呢?

杨达:我觉得中越有一些差不多的问题,所以中越之间可能有一些借鉴的可能,比如两国都是从社会主义计划经济改过来的,所以他们共同的问题还是比较多,是有参考的价值。

德国之声:越南在政治改革这方面会不会比中国进行得更快呢?

杨达:我个人的了解是越南在政治改革方面可能会快一些。我了解他们党内在这方面是公开的。这和现在中国的情况有些不同。当然也要考虑越南的国情跟中国不同。越南国内的问题也比中国严重,比方说经济方面,尤其是通胀方面可能比较严重。越南期望跟某些国家发展更多的关系,比如越南本身也希望跟美国有比较友好一些的关系,也希望与其他东南亚国家发展关系,融入东南亚,尤其是东盟。所以,越南这方面的改革可能会快一些。

德国之声:战争过去30年后是否仍在越南民众心中留下很多阴影呢?您也知道,在中国,特别是80,90年代,很多舆论宣传,电影还是给中国人民心中越南人的形象造成了非常大的影响的。

杨达:我的了解是,在越南,中国的有些文化产品还是很流行的,比方说中国的电视剧。因此,阴影我不排除,一定有的,但同时我觉得中越关系从现在的角度,尤其是以新一代的角度看,可能有些不同。

德国之声:越南有没有感到中国是一个威胁,中国威胁论在越南是不是也被人接受呢?

杨达:多少也有。因为中国是一个很大的国家。如果我们从东南亚的角度看-还有其它国家,比如说东北亚韩国的角度看也是一样-中国的发展其实多多少少是一个威胁。从我们临近的国家来说,多多少少有些担心。我觉得中国的外交政策一般来说是希望减低这种担心,尽可能利用中国所谓的经济,贸易优势吸引他们。我觉得跟越南的关系也是一样的。

傅悦

Chinese Invasion of Vietnam

February 1979

China’s relations with Vietnam began to deteriorate seriously in the mid-1970s. After Vietnam joined the Soviet-dominated Council for Mutual Economic Cooperation (Comecon) and signed the Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation with the Soviet Union in 1978, China branded Vietnam the “Cuba of the East” and called the treaty a military alliance. Incidents along the Sino-Vietnamese border increased in frequency and violence. In December 1978 Vietnam invaded Cambodia, quickly ousted the pro-Beijing Pol Pot regime, and overran the country.

China’s twenty-nine-day incursion into Vietnam in February 1979 was a response to what China considered to be a collection of provocative actions and policies on Hanoi’s part. These included Vietnamese intimacy with the Soviet Union, mistreatment of ethnic Chinese living in Vietnam, hegemonistic “imperial dreams” in Southeast Asia, and spurning of Beijing’s attempt to repatriate Chinese residents of Vietnam to China.

In February 1979 China attacked along virtually the entire Sino-Vietnamese border in a brief, limited campaign that involved ground forces only. The Chinese attack came at dawn on the morning of 17 February 1979, and employed infantry, armor, and artillery. Air power was not employed then or at any time during the war. Within a day, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) had advanced some eight kilometers into Vietnam along a broad front. It then slowed and nearly stalled because of heavy Vietnamese resistance and difficulties within the Chinese supply system. On February 21, the advance resumed against Cao Bang in the far north and against the all-important regional hub of Lang Son. Chinese troops entered Cao Bang on February 27, but the city was not secured completely until March 2. Lang Son fell two days later. On March 5, the Chinese, saying Vietnam had been sufficiently chastised, announced that the campaign was over. Beijing declared its “lesson” finished and the PLA withdrawal was completed on March 16.

Hanoi’s post-incursion depiction of the border war was that Beijing had sustained a military setback if not an outright defeat. Most observers doubted that China would risk another war with Vietnam in the near future. Gerald Segal, in his 1985 book Defending China, concluded that China’s 1979 war against Vietnam was a complete failure: “China failed to force a Vietnamese withdrawal from [Cambodia], failed to end border clashes, failed to cast doubt on the strength of the Soviet power, failed to dispel the image of China as a paper tiger, and failed to draw the United States into an anti-Soviet coalition.” Nevertheless, Bruce Elleman argued that “one of the primary diplomatic goals behind China’s attack was to expose Soviet assurances of military support to Vietnam as a fraud. Seen in this light, Beijing’s policy was actually a diplomatic success, since Moscow did not actively intervene, thus showing the practical limitations of the Soviet-Vietnamese military pact. … China achieved a strategic victory by minimizing the future possibility of a two-front war against the USSR and Vietnam.”

After the war both China and Vietnam reorganized their border defenses. In 1986 China deployed twenty-five to twenty-eight divisions and Vietnam thirty-two divisions along their common border.

The 1979 attack confirmed Hanoi’s perception of China as a threat. The PAVN high command henceforth had to assume, for planning purposes, that the Chinese might come again and might not halt in the foothills but might drive on to Hanoi. The border war strengthened Soviet-Vietnamese relations. The Soviet military role in Vietnam increased during the 1980s as the Soviets provided arms to Vietnam; moreover, Soviet ships enjoyed access to the harbors at Danang and Cam Ranh Bay, and Soviet reconnaissance aircraft operated out of Vietnamese airfields. The Vietnamese responded to the Chinese campaign by turning the districts along the China border into “iron fortresses” manned by well-equipped and well-trained paramilitary troops. In all, an estimated 600,000 troops were assigned to counter Chinese operations and to stand ready for another Chinese invasion. The precise dimensions of the frontier operations were difficult to determine, but its monetary cost to Vietnam was considerable.

By 1987 China had stationed nine armies (approximately 400,000 troops) in the Sino-Vietnamese border region, including one along the coast. It had also increased its landing craft fleet and was periodically staging amphibious landing exercises off Hainan Island, across from Vietnam, thereby demonstrating that a future attack might come from the sea.

Low-level conflict continued along the Sino-Vietnamese border as each side conducted artillery shelling and probed to gain high spots in the mountainous border terrain. Border incidents increased in intensity during the rainy season, when Beijing attempted to ease Vietnamese pressure against Cambodian resistance fighters.

Since the early 1980s, China pursued what some observers described as a semi-secret campaign against Vietnam that was more than a series of border incidents and less than a limited small-scale war. The Vietnamese called it a “multifaceted war of sabotage.” Hanoi officials have described the assaults as comprising steady harassment by artillery fire, intrusions on land by infantry patrols, naval intrusions, and mine planting both at sea and in the riverways. Chinese clandestine activity (the “sabotage” aspect) for the most part was directed against the ethnic minorities of the border region. According to the Hanoi press, teams of Chinese agents systematically sabotaged mountain agricultural production centers as well as lowland port, transportation, and communication facilities. Psychological warfare operations were an integral part of the campaign, as was what the Vietnamese called “economic warfare”–encouragement of Vietnamese villagers along the border to engage in smuggling, currency speculation, and hoarding of goods in short supply.

http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/war/prc-vietnam.htm